Crisis 22

Shadow Stories

Introductions - States of Mind - Cunning Plans - Puppet Masters - Fearless Leaders - Coda

🌗

Introductions

On this page I give brief summaries of every section and page in Crisis 22. I cover dominant topics and themes, and place the pages within the larger context of my argument.

🗝 A Literary Premise introduces the aims of this project, and explains its literary premise: serious literature reflects dilemmas large and small, local and international. Because this literature integrates personal, cultural and historical dimensions, it can help us make sense of the type of complex scenario we find in the Ukraine Crisis today.

🌗 Shadow Stories (this page) gives brief introductions to all the sections and pages in Crisis 22. I start by explaining my various uses of narratives — 🔸 those that are complex, ambiguous, and layered (like global politics), 🔸 those that we use to make ourselves feel better (“Everything is OK, the Crimea was Russian anyway”), 🔸 those that are manipulative vs. self-critical (Putin vs. Bulgakov), and 🔸 those that give us two or more perspectives at once (for example, 1) how we see Russia and 2) how Russians see Russia).

One way to understand complex situations like we find in Ukraine is to understand complex narratives, which are often found in long poems and serious plays and novels — as opposed to comedies and lighter fare. Especially helpful in understanding today’s ruthless, slippery realm of politics — which is replete with propaganda, misinformation, distortion, cyber attacks, spies, cloak and dagger diplomacy, etc. — are complex narratives that are also ambiguous or layered. In these narratives, actions and motives lie in shadow, as if under a veil or behind a screen. As readers, we have to interpret explicit words and gestures, and we also have to guess what’s going on behind the scenes. The writer urges us to ask ourselves, Who’s pulling the strings?

This type of narrative is especially relevant to the cloaked realm of Kremlin politics and espionage, especially since Putin comes from, and still controls, the Russian spy agency (the KGB and later the FSB). Also, the Ukrainians must be cunning if they want to penetrate the Russian system — or keep secrets of their own. And, of course, the off-stage actors in the international drama — notably China and the US — are also known for their management of secrets, deep fakes, implanted spies, and subterfuge. As Dick Cheney once said, in global politics there are “known unknowns.” And when it comes to the greatest stakes — nuclear stakes — no one knows these unknowns better than the Kremlin and the Pentagon.

Often political narratives seem to float on the surface, or dance and dart like shadow-puppets on a screen. This is where Christopher Koch’s novel The Year of Living Dangerously is helpful: in it Koch makes extensive, elaborate and subtle use of the Indonesian shadow-puppet theatre, the Wayang Kulit. He invites the reader to see the story as it appears on the screen — or to look behind the screen, where the puppet-master plies his trade. This narrative strategy urges us to ask, How can we understand what the hidden puppet-master has in mind, deep in his office in the Pentagon or Kremlin, the Élysée Palace or 10 Downing Street, Jade Spring Hill or 7 Lok Kalyan Marg?

I conflate this shadow theatre notion with the paradigm Rushdie uses in Haroun and the Sea of Stories: an ocean of narratives that are continually changing, dividing, and fusing. This conflation urges us to see from both sides of the screen, and also to shift our views if necessary, so as not to get stuck in the same old story.

I also use the notion of narrative or story-telling to talk about the shift from the 20th century Cold War to that blessed quarter century of European peace (from roughly 1989 to 2014), to the return of war in 2014 and 2024. We once believed in the possibility of a happily ever after ending to the narrative of the Cold War story. Some, like Fukiyama, even talked about the end of history, as if we were entering a Golden Age of liberal democracy. This was of course a fiction, and ignored all types of problems in Kosovo, Chechnya, Georgia, Afghanistan, Syria, etc. The golden European aura dimmed considerably with the Russian incursions of 2014 into Crimea and the Donbass, and then closer to home with the sad spectacle of Donald Trump, who turned the bulwark of democracy into a divided state. One half of the American political system plunged into demagoguery, election denialism, and deep skepticism about the validity of journalism and the institutions of state.

Still, from 1989 to 2024 many of us in the West remained in a sweet dream state — until all of a sudden in 2024 we realized that there is, unfortunately, a sequel (rather than a post-script) to the end of history’s narrative.

In trying to understand Putin’s war we might also look at two types of stories that Russians tell themselves. On the one hand we have stories about their imperial destiny, their special military operation, and their struggle against the wicked warlock of the West. These stories dominate at the moment in Russia, partly because Russians believe them and partly because they’re coerced and manipulated into believing them. Rarely do we hear that other type of story, the type told by their great 19th and 20th century novelists, such as Gogol or Bulgakov. These stories urge Russians to question themselves, their rulers, and their serf or Soviet systems. Some of these stories even urge Russians to question the chauvinistic drive behind the imperialism they’ve supported for the lasted 700 years.

🌗

☕️ Coffee in St. Pete’s explains my literary and personal take on Russia and the war. I see literature as a borderless merging of disciplines and perspectives, yet also as a holistic realm of exploration which delves deeply into any topic — including politics, global conflict, and war. Literature explores our psychologies — the flow of our thoughts & feelings, our natures, identities, etc. — and it allows us to peer into other identities, cultures, ideas, political visions, etc. In regard to the Ukraine War, one might recall that the first great works of Western and Indian literature — the Iliad & Odyssey, the Mahabharata & Ramayana — focus on specific wars, yet also supply wide-ranging insights into psychology, culture, philosophy, religion, etc.

💥 Exceptional Violence summarizes the superpower conflict as I see it in August 2024. While I think Russia and the U.S. made big mistakes in Eastern Europe, Vietnam, Chechnya, Afghanistan, and Iraq, Russia is making an enormous mistake in Ukraine.

🟢 Fog & Shadow and 🌏 The Global South look at why I think it’s important to understand foreign ways of looking at the world. I suggest that paradigms such as the Indonesian shadow theatre can help us see conflict in a new and holistic light. Understanding this type of paradigm might also help us communicate more effectively with the global south, which largely shares our beliefs in democracy and national sovereignty. Certainly this is the case demographically, since the most populous countries are all democracies: India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Brazil, as well as almost all the countries of Latin America.

Note: I find the term global south to be a bit odd, since much of it lies north of the equator. Also, Australia and New Zealand clearly are in the south yet they aren’t part of that group. And yet global south does get at the basic idea of a swath of countries that are generally to the south and that have consistently resisted falling into the orbit of the U.S, Europe, Russia, or China. Perhaps a better name for this area would be the central wave or the middle fin:

🌗

States of Mind

The section States of Mind gives a personal take on the war. I look at the way many of us were shaken by the Russian invasion, and at ways we might cope with crisis overload.

The first three pages in States of Mind chronicle 1. my long-standing fear of nuclear war, 2. my attempt to ignore the latent problems within Russia, and 3. my shock at the events of 2022.

⏳ The Ghost of Crises Past compares my fears today with 1. Shelley’s mix of pessimism and optimism in early 19th century England, and 2. my fears during the Cold War in the 1980s.

✈️ Dream Vacation 2005 is a nostalgic take on travelling to St. Petersburg, Moscow, Vladímir, and Suzdal. I look back at that 2005 trip and sigh. I think Ah, a Russia that could have been...

In⛱️ Rip Van Winkle I illustrate how I went abruptly from 30 years of self-induced dreaminess to a present state of high anxiety — as if a siren blasted a tsunami alert while I was sitting comfortably on a Cuban beach smoking a cigar and drinking a rum and coke, in the early evening, as the sun set over the fine sands of Playas del Este…

Left: Playas del Este, Cuba. Right: “Kyiv after Russian missile strikes on 10 October 2022. Intersection of Volodymyrska Street and Taras Shevchenko Boulevard” (from Wikimedia; source page from State Emergency Service of Ukraine).

In 🌉 Jovanka on the Bridge (July & October 2023) I stress how disturbing it is to follow the news about an asymmetrical war in which thousands are killed every day, and in which Russian priests are blessing bombs.

☯️ Both In and Out of the Game argues that we can’t ignore the Ukraine War, and yet we can’t let ourselves get swallowed by it either. I suggest a third option, a mode of being in which we engage and disengage at the same time. Walt Whitman provides one version of this, in which he faces “the horrors of fratricidal war, the fever of doubtful news, the fitful events” yet also remains “Apart from the pulling and hauling […] both in and out of the game.”

❄️ Political Modes of Being explores similar modes of engaging & escaping, this time in the poetry of Eliot & Keats, in the stoicism of Marcus Aurelius, and in any religious philosophy which allows for the defensive use of violence.

🌗

Novels

In the next two sections I use novels — which I think of as small complex worlds unto themselves — to get at the complex and colliding worlds that are laid bare (or lie hidden beneath) the surface of the present global crisis. Cunning Plans takes a close look at Dead Souls (1842), Nikolai Gogol’s startling peek into the mind and manners of provincial 19th century Russia. Gogol’s novel also deals with Russian identity and with Russia’s stagnant social system. Puppet Masters delves into The Year of Living Dangerously (1978), Christopher Koch’s depiction of 1965 Cold War Indonesia. Koch’s novel also deals with poverty, identity crisis, loyalty and betrayal, national and international conflict, and the difficulty of understanding who’s pulling the political strings. While the focus is on Indonesia, so much of what Koch writes about is germane to the internal conflicts and the strategic uncertainties that lie between Moscow and Kiev.

In Cunning Plans and Puppet Masters I also use a variety of other novels: Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (a stunning novel that ranges from Pilate’s Jerusalem to Stalin’s Moscow), Greene’s The Quiet American (about the French in 1950s Vietnam), and Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children and Shame (about the Indian subcontinent in the 20th century). Dead Souls and The Master and Margarita allow for historically-distanced yet culturally apposite critiques of Russian identity (and Putin’s version of this identity), while Year, The Quiet American, Midnight’s Children & Shame examine foreign forms of cultural and political expression, which will come in handy if we want to convince the rest of the world that the Kremlin is wrong.

🌗

Cunning Plans

I begin my look into Dead Souls with 🧥 Two Novels and an Overcoat, which explains how Dead Souls and Year work in a complementary manner: one delves into the absurd scams of selling souls and selling a special military operation, while the other delves into what happens when all political hell breaks loose. I’ll use Dead Souls to illustrate the Kremlin’s mistaken take on cultural identity and international order, and I’ll use Year to suggest that we can understand the rest of the world better than the Kremlin can — if that is, we continue to avoid the colonial view that our culture, our politics, and our conception of the world are the only ones we need to emphasize.

I’ll also suggest that Gogol’s short story “The Overcoat” gives us a wonderful metaphor by which to ponder the Russian state of mind. What lies hidden beneath the Russian overcoat, pamphlets of rebellion or items to barter? Will Russians revolt against Putin or will they continue to swap his guarantees of security for their blind allegiance?

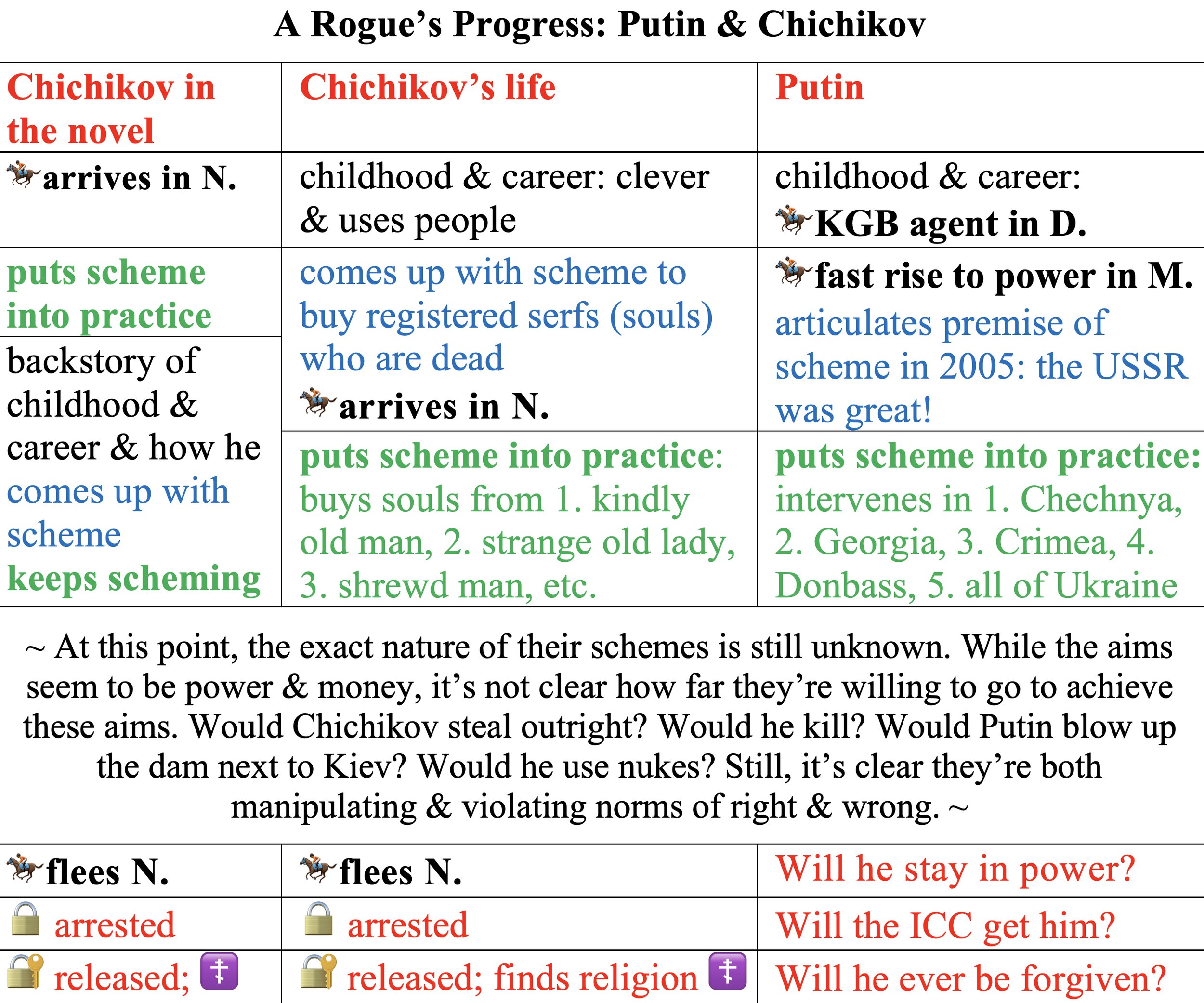

In 😵💫 Russian Souls and ✒️ Literature & Subversion I’ll argue that just as Gogol’s townspeople are slow to figure out the scam perpetrated by the protagonist (Chichikov), so Russians are slow to see through Putin’s excuses for war and through his distorted notions of patriotism and the Russian soul. All of these are convenient ways to promote Empire, which ought to go the way of feudalism, serfdom, and colonialism. I’ll also argue that Gogol’s critique of Russian character and institutions is echoed in the Soviet-era writer Mikhail Bulgakov, and that this type of critique is more universal than some critics think: it isn’t just a function of a Russian soul, but of humanity in general.

💰 Selling the Scheme (not yet online) looks more closely at Dead Souls, comparing how Putin sells his special military operation to the way Chichikov sells his scheme to buy dead souls (or deceased serfs):

Two further pages are also unfinished: 🧛🏻♂️ The Immoralities of Marmeladov and Raskolnikov looks at the plans of Chichikov and Putin in light of the drunken logic of Marmeladov and the ruthless gambit of Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. 🚓 Crimes and Punishments looks at the crimes of Chichikov and Putin in light of the justice and injustice of the world, — a world in which the words of Shakespeare’s villain Claudius are all too true:

🌗

Puppet Masters

The Year of Living Dangerously isn’t as obviously germane to Putin and his war as is Dead Souls — although I could imagine a chart comparing the Old Cold War in Southeast Asia to the New Cold War in Europe. Instead of making a close, character-oriented comparison between Koch’s novel and Putin’s war, I use The Year of Living Dangerously to get an intimate yet also distanced look at large-scale conflict.

Koch sees large-scale events — the political crisis that shifted Indonesia from the left-wing Sukarno to the right-wing Suharto — through individual characters and through a metafictional narration. His novel thus gives us a personal and intimate, as well as a philosophical or mythic, look into at least six things that are very relevant to the present crisis in Ukraine: 1. the collateral human damage of superpower conflict (that is, how large scale politics affect average people), 2. the use of distortion and propaganda (Sukarno and Putin are masters of the art), and 3. the inability of outsiders to understand what’s going on at the highest levels of power, especially during a proxy conflict. How much do we really know about what the Kremlin and Pentagon are planning?

I also use Year to look into 4. the ongoing question of how the West might better understand the previously colonized countries in the global south. Many of these ‘southern’ countries (most notably India) nominally support Russia. They tolerate what Russia is doing, largely because of historical and economic reasons. Instead of brushing off their minimalist or non-aligned allegiance, we might determine to understand these countries more deeply. Koch’s depiction of Cold War Indonesia is a good place to start, since it not only looks into the four things I just listed, but also 5. contains both Western and Eastern perspectives. In the compact and easily-digested form of a novel, Koch goes into structural and cultural detail about how one might see politics from both Western and Indonesian points of view. Perhaps more importantly, he gives us a sense of how to deal with our own inability to penetrate the depth of other cultures.

As an example of what I mean, we see Year’s protagonist Hamilton at the end of the novel, his eye bludgeoned by Jakarta’s Palace guards, his mind finally accepting that he doesn’t know what’s going on. He tries to give advice to his assistant Kumar, who he knows to be an agent for the communist leader Aidit:

Hamilton said into his darkness, knowing it was useless, ‘Don’t follow that bastard Aidit: they’ll kill you out there along with him. I’ve already told [the Australian Broadcasting Service] you’re the best man we could possibly have. You deserve… He broke off. It was stupid, trying to tell Kumar what he deserved.

‘Thank you but I will follow Comrade Aidit. His day will come. Think of me when you are sitting in some nice café in Europe.’ The voice became softer again. ‘In my dreams, I am always sitting at a table by the footpath, drinking coffee, with flowers growing in tubs.’ The hand was withdrawn, and the voice, with perhaps a note of irony, used Hamilton's name for the first and last time. ‘Good-bye, Guy.’

His footsteps went quickly to the door, which opened and closed with discreet quietness.

Koch’s novel also 6. leads historically and geopolitically into the treatment of the Cold War catastrophes we see in Graham Greene’s The Quiet American (1954) and Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five (1968).

More specifically, I look at The Year of Living Dangerously on the following pages.

🇮🇩 Literature & Politics argues that Koch’s novel helps us understand the human dimensions of historical crisis: the personal experiences he describes are deeply embedded in narrative structures that mirror complex political and social realities.

⚔️ The Dangerous Years takes a more in-depth look at the narrative structure of Koch’s novel, illustrating how it might be used to understand the Ukraine Crisis.

🌪 The Eye of the Storm argues that Putin pretends to be a champion of a new world order, yet he effectively stirs up havoc and violence all around him, slaughtering Ukrainians and harming the very people he pretends to help. In this, he exhibits the worst of both the left-wing propagandist Sukarno and the right-wing strongman Suharto.

Several pages on Year are not yet online. 🎙️ Words of Folly and Wisdom contrasts propaganda and religious distortion with words of understanding, reconciliation, and peace. ⚔️ Battle of the Puppets looks at the way people turn against each other, betray each other, and prepare the world for slaughter.

✨ The Dark Which Has No End (in progress) suggests a literary and mythic way of contextualizing and understanding apocalyptic violence. One can of course look at cataclysm or apocalypse in many ways: a complete annihilation of anything human, a Rapture in the Christian tradition, or an infinite stretch of space that loops in and out of existence, as in the image of Vishnu in cosmic space, creating universes (which are eventually destroyed) and resting on the eternal snake Shesha:

This image may seem strange, but that’s the point: it’s the type of different paradigm that we might consider — if, that is, we’re going to understand and communicate with those in the global south who are more familiar with Krishna than Christ.

By using The Year of Living Dangerously I hope to suggest a very different way of looking at the present crisis. In the West we often fail to understand the experience of those who were once colonized and who are now sometimes referred to as the global south. For instance, after the Indian Prime Minister visited Putin on July 9, 2024 much was made of their bear-hug — a truly cringe-worthy moment where we saw the leader of the world’s largest democracy tightly hugging the leader of Europe’s largest country fighting democracy. Yet little was made of the critical, deeply emotional words Modi spoke to Putin about the death of children, and about the tragedy of war:

Whether it is war, conflict or a terrorist attack, any person who believes in humanity is pained when there is loss of lives […] But even in that, when innocent children are killed, the heart bleeds and that pain is very terrifying […] Amidst guns, bullets and bombs, peace talks cannot be successful.

Modi’s words weren’t made behind the scenes in a private meeting, but in a televised forum. His words came just hours after Russia bombed the children’s hospital in Kiev. While I wish Modi would more directly criticize Russia for its aggression, I found some comfort in watching Putin nervously wriggle his feet as he’s being told, once again by his Indian friend, that violence isn’t the way to go.

🌗

Rushdie

In 🇮🇳 India & the Many-Headed Monsters and 🇵🇰 Pakistan & the Fall of the Poet (both still in progress), I explore the way Salman Rushdie at once educates and entertains us in the largest and most consequential region of the global south: the Indian subcontinent. I’ll look at two of his early novels, Midnight’s Children (1981) and Shame (1983), which together form of sort of history of the subcontinent from around 1915 to 1980. I’ll also look at his later children’s novel, Haroun and the Sea of Stories (1990).

Koch and Rushdie both explore the following subjects, all of which are relevant to the Ukraine Crisis: 1. manipulative autocracy and brutal dictatorship, 2. propaganda leading to internecine war, 3. the collateral damage caused by political and military conflict, 4. complex layers of narrative and ambiguous layers of understanding, and 5. paradigms used to understand politics and society in the global south: the Wayang in Koch and the conference of the birds and the ocean of stories in Rushdie. The first three of these subjects are obviously applicable to the Ukraine Crisis, while the last two are more subtle.

Being subtle, they are quite malleable and can be applied very widely. For instance, they can help us understand different ways that geo-political and cultural situations are understood outside of the West. They can also be used to understand and communicate with nations in the south which are democratic and respect national sovereignty yet are subject to Russian economic pressure and anti-colonial rhetoric.

Finally, they can be used as mechanisms to get a conceptual distance from the present Ukraine Crisis. They can present us with a way of seeing its complexity without getting stuck in the details of our own paradigms. For example, most Western readers don’t have a specific point of view in regard to Attar’s conference of the birds, in which all divisions are obliterated in the unity of God, or Somadeva’s ocean of stories, where all narratives are mixed and altered. On the other hand, most Western readers tend to have a specific bias for or against the Garden of Eden or the Rapture. By seeing the Kremlin’s point of view as an errant flight that the infinite sky will end, or as a muddy stream the ocean will subsume, we might think about how the Kremlin line can be diffused or rendered less muddy. We also might avoid falling into our own paradigms of Garden and Rapture, which tend to urge us to see the Russian narrative as evil and serpent-like, and as a harbinger of a pre-ordained Apocalypse.

The ocean of stories is like the universe itself: tugged and pulled by the forces of darkness and light.

In the battles [the power-hungry asuras] gained control over the three worlds. The [benevolent] devas sought Vishnu's wisdom, who advised them to treat with the asuras in a diplomatic manner. The devas formed an alliance with the asuras to jointly churn the ocean for the nectar of immortality, and to share it among themselves. However, Vishnu assured the devas that he would arrange for them alone to obtain the nectar. (From Wikipedia).

🌗

Fearless Leaders

Crisis 22 also contains several pages focused on history & politics as they relate more exclusively to the Ukraine War. On these pages I look at the following topics: global leadership, sovereignty rights, blame, war crimes, and exit strategies.

✊ Fearless Leader of the Global South uses Koch’s Year of Living Dangerously and the French scholar Bertrand Badie in order to contrast the legitimate Indonesian postcolonial aims of the 1960s to the opportunistic Russian colonial aims of the 2020s.

🇺🇦 Golden Bridges (July 2022) looks at the question of blame, sanctions, and double standards, arguing that 1. we need to come clean about the abuses of the West, and 2. we need to make clear, especially to the global South, why these abuses don’t mean that we can remain neutral toward the Kremlin and its illegal, unnecessary, disastrous war.

In 🇺🇸 / 🇷🇺 Exceptionalism (December 2022) I focus on the unparalleled entitlement and immunity that get Russia in hot water today, as it got the US in the past. The concept of exceptionalism largely explains why neither nation will submit to the judgments of the International Criminal Court. This makes it hard to argue that Putin must take responsibility for his brutality in Ukraine, despite the fact that no one has taken responsibility for the bombs, napalm, and dioxin flung over the forests and villages of Indochina. The global south has historical memories that ought to be recognized if we’re to succeed in getting them to help Ukraine.

In 🗽Our Lady of the Harbour (2023 & 2003) I suggest that despite needing to arm Ukraine and defend our ideals, we still need to limit all nuclear weapons. Finally, ☮︎ War: A Brief Playlist of Songs & Poems comments briefly on poems and lyrics about war.

🌗

Coda

The final section contains a poem and two short stories.

🦋 The Tao of Putin contains a very brief poem which depicts the Russian atrocities in Bucha in terms of Daoist symbolism. I compare and contrast Zhuangzi’s mystic butcher with Putin, who cuts “with the sharpest of blades, extracting the vile Nazi within. / Working within the confines of invisibility, / he must find the empty space between the Slavic bone.”

🍒 Macaron, Not Macron aims at a comic distance from the present catastrophic dangers. It features a New York lawyer who is so obsessed by artistic beauty and by his transexual assistant that he can’t see the skyscrapers falling all around him.

Finally, ⏳ AD / BC is an apocalyptic vision that suggests a link between war in Ancient Mesopotamia and present-day Ukraine. In this short story, an old professor is wheeled to a cafe in Penticton in the summer of 2022. He imagines he hears the faraway silos open and he remembers, only in fragments, the discovery of a 4044 year-old tablet he found in Iraq back in 2003, while the bombs were dropping all around him …

From my seat at the window of Blenz Café, I see the professor of Ancient philology in his wheelchair. Once a specialist in the ancient languages of Sumer and Akkad, Professor Clay now babbles, seemingly incoherent, about the end of time and the thunder-stroke of Uzhur. …

🌗