The Double Refuge 🦖 At The Wild & Fog

Jardine’s Monkeys

In Dickens’ day there were skeptics and atheists, yet most respectable scientists and thinkers assumed a great many religious things that we simply don’t assume today. By looking at the writings of Hutton and others we can see how prevalent religious ideas were, and how hard it was to think apart from them. We see this 30-odd years after Hutton’s Theory in the writings of John Abercrombie, who argues that science may make us lose our way if we forget scripture. The Dickens scholar Susan Shatto refers to Abercrombie's writing in relation to Esther's psychological dream-like state in Chapter 35, noting that Dickens had Abercrombie’s writings in his library. For convenience, I’ll put in bold the ideas which are clearly religious, yet are mixed into his 1830 Inquiries Concerning the Intellectual Powers and the Investigation of Truth:

As the judgment advances to maturity, and the sad realities of life force the mind into more practical channels of thought, conscience reasserts her dominion, the power of the world to come begins to put forth its holy influence, and the knight-errant of philosophy is transformed into the sober soldier of ordinary life. […] the philosophy of the mind can be safely studied only as an accompaniment to theology, or as superstructure on the foundation of a mathematical and physical science. The study of theology has a direct and immediate tendency to check the temerity of speculation, and to mortify the presumption of intellectual vanity. Its doctrines become powerful barriers against the excursive extravagances of scepticism; and the duties which it enjoins, and the aspirations which it cherishes, contribute to give a fixed and practical direction to the current of our speculations.

The same deep linkage between religion and science occurs in Jardine's 1833 study of monkeys. Jardine’s study at once shows why a writer might make comparisons between apes and the great ape man (they even share a love of wine!) and also why it was taboo to equate the two (since the humans are more intelligent and “Godlike erect”). In The Natural History of Monkeys (1833), Jardine writes:

Among the greater part of them, the love of wine or diluted spirits becomes almost a passion; they are often offered as bribe to the performance of various tricks, and they will always be greedily drunk when left within reach. Vosmaer's orang, one day when loose, commenced its exploits by finishing a bottle of Malaga wine. Happy Jerry, the ribbed nose baboon in Exeter Change, performed all his tricks upon the anticipation of a glass of gin and water; and the relish and expression with which it was taken, would have done honour to the most accomplished taster.

We do not intend to institute a strict comparison between the monkey and human organization, and to adduce proof from the comparison, that they are distinct as well in structure as in nature we consider this quite unnecessary, and think that in all our systems, man should be kept entirely distinct. As he is infinitely pre-eminent by the high and peculiar character and power of his mind, and the future destination of his immaterial part, so has he been stamped with a bearing lofty and dignified, with “Far nobler shape, erect and tall, Godlike erect, with native honour clad."

Even though Jardine is a primatologist, he still thinks in religious terms about the future destination (the afterlife) and about the immaterial part (the soul). Like many scientists, agnostics have no quarrel with him thinking about the spiritual side of humans, yet they see his insistence on the superior spiritual state of humans as a belief, not as a fact which can be reasonably asserted in a scientific study. Man is no doubt “infinitely pre-eminent by the high and peculiar character and power of his mind,” yet as Dickens makes crystal clear in simple-minded characters from Skimpole to Chadband, and in the sharper-minded people from Jellyby to Tulkinghorn, this doesn’t make them superior, let alone God-like.

Dickens gives chapter 21 the title, The Smallweed Family, which is an ingenious pun, since the Smallweed family is seen in terms of zoological family, Grandfather Smallweed decidedly on the simian side of the primates. A thoroughly dislikable man, the grandfather is depicted as both ape-like and machine-like — a non-human greedy machine that needs punching and re-arranging before it can operate normally. In chapter 20, the grandfather drinks and smokes in a monkeyish way, reminiscent of “Vosmaer's orang … finishing a bottle of Malaga wine” (in the Jardine quote above), yet the old man also seems to incarnate the notion of ancient life itself, and thus allows Dickens an opportunity to mock Law and Equity (and indirectly the antiquated early-1800s version of Chancery):

he is a weird changeling, to whom years are nothing. He stands precociously possessed of centuries of owlish wisdom. If he ever lay in a cradle, it seems as if he must have lain there in a tail-coat. He has an old, old eye, has Smallweed; and he drinks, and smokes, in a monkeyish way; and his neck is stiff in his collar; and he is never to be taken in; and he knows all about it, whatever it is. In short, in his bringing up, he has been so nursed by Law and Equity that he has become a kind of fossil Imp, to account for whose terrestrial existence it is reported at the public offices that his father was John Doe, and his mother the only female member of the Roe family; also that his first long-clothes were made from a blue bag [used for legal documents].

In Chapter 20 we also find odd statements about things that link to religious history and science, such as the development of languages (as when “the waitress returns, bearing what is apparently a model of the tower of Babel, but what is really a pile of plates and flat tin dish-covers”) or the literalist’s notion of a flat world — as when the phrase coming round prompts the narrator to comment, “That very popular trust in flat things coming round! Not in their being beaten round, or worked round, but in their ‘coming’ round! As though a lunatic should trust in the world’s ‘coming’ triangular!”

In Chapter 21: “The Smallweed Family,” the monkeyish fossil Imp that mocks the Law becomes an insect that mocks the banking system: Grandfather Smallweed is “a horny-skinned, two-legged, money-getting species of spider, who spun webs to catch unwary flies, and retired into holes until they were entrapped. The name of this old pagan’s God was Compound Interest.” Dickens further dehumanizes “the house of Smallweed” by suggesting that it’s mechanical greed leaves little room for valuable things like imagination, art, and literature. He thus echoes Jardine’s notion that “man should be kept entirely distinct” from monkey:

During the whole time consumed in the slow growth of this family tree, the house of Smallweed, always early to go out and late to marry, has strengthened itself in its practical character, has discarded all amusements, discountenanced all story-books, fairy tales, fictions, and fables, and banished all levities whatsoever. Hence the gratifying fact, that it has had no child born to it, and that the complete little men and women whom it has produced, have been observed to bear a likeness to old monkeys with something depressing on their minds.

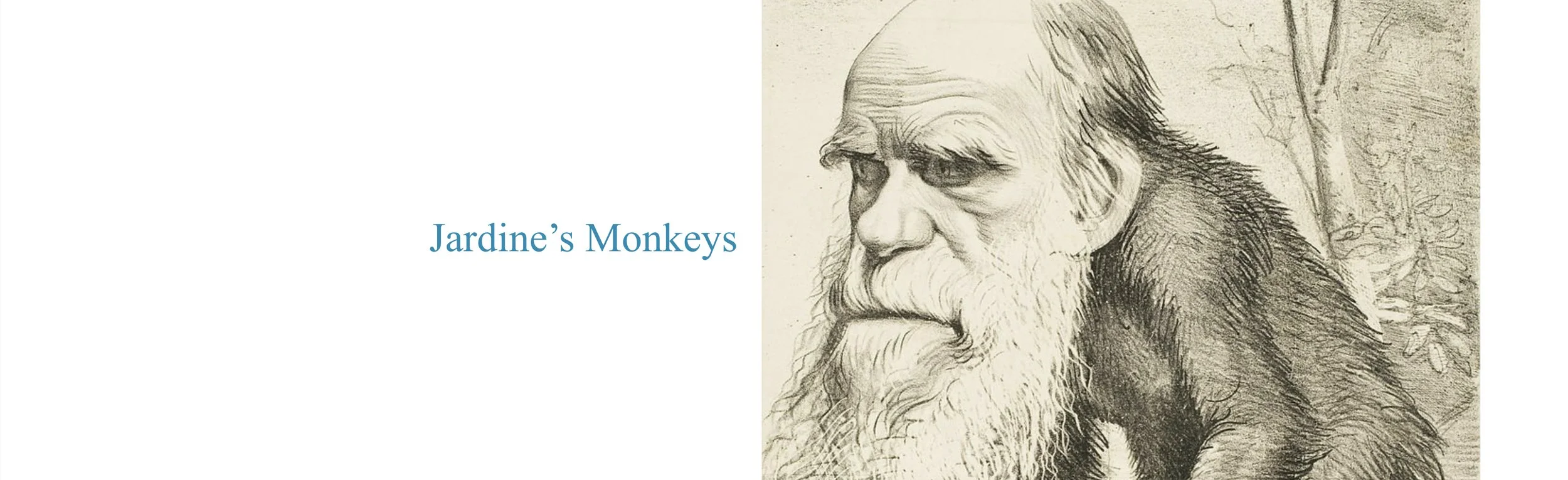

Dickens steeps the chapter in notions of human genealogy, a discipline which intersects with that of animal evolution, although the relation isn’t a clear one in 1852. The study of genetics hadn’t even properly begun: Gregor Mendel published his article "Experiments on Plant Hybridization" in 1865, and DNA wasn’t fully understood until the early 1950s. The general connection was of course made by Darwin in 1859, yet the deeper import of the relation was immediately resisted, as we see in this famous caricature of the great scientist as half-human, half-monkey:

My point here is that Dickens is writing before Darwin, Mendel, and Watson and Crick, yet he is still deeply influenced by recent studies in geology and zoology. In keeping with his genealogical account, Dickens goes from describing the grandfather to describing the grand-daughter Judy, who despite her relative youth is depicted as ancient: she “appears to attain a perfectly geological age and to date from the remotest periods.” Dickens stresses her link to her monkey family:

[Judy] so happily exemplifies the before-mentioned family likeness to the monkey tribe, that, attired in a spangled robe and cap, she might walk about the table-land on the top of a barrel-organ without exciting much remark as an unusual specimen. Under existing circumstances, however, she is dressed in a plain, spare gown of brown stuff.

Dickens again stresses the stark sub-humanity of this sad monkey tribe:

Judy never owned a doll, never heard of Cinderella, never played at any game. […] She seemed like an animal of another species […] And her twin brother couldn’t wind up a top for his life. He knows no more of Jack the Giant Killer, or of Sinbad the Sailor, than he knows of the people in the stars.

Dickens’ depiction of the Smallweeds is a vehicle for his attack on greed. Yet its nastiness seems to reflect a fear that Victorians shared more with monkeys than their preachers were willing to grant. While Dickens understandably follows writers like Jardine in depicting monkeys as completely alien to “higher” human thinking and feeling, how exactly does the narrator know anything more than the monkey tribe about “the people in the stars”? At this point there appears to be a break between the Dickensian narrator and Dickens himself, who may be wondering if we know as much as we pretend to know. The last simian image we see is the grandfather in Chapter 26 “turning up his velvet cap, and scratching his ear like a monkey.”

🦖

Next: Darwin’s God