Crisis 22

AD / BC

[This story uses Mesopotamian myth — see notes at the end. The opening quote is from The Epic of Gilgamesh.]

⏳

Gilgamesh said [to Enkidu], “I had another dream. We were in a deep gorge of the mountain. Next to the mountain we were like mosquitoes. Suddenly the mountain fell on us. Then there was a terrible light, and in it was one whose grace and beauty are greater than the beauty of the world. He pulled me out from under the mountain, and gave me water to drink. My heart was comforted as he set my feet on the ground.”

Penticton, July 7, 2022

From my seat at the window of Blenz Café, I see the professor of Ancient philology in his wheelchair. Once a specialist in the ancient languages of Sumer and Akkad, Professor Clay now babbles, seemingly incoherent, about the end of time and the thunder-stroke of Uzhur.

The care-aid pushes his wheelchair onto the sidewalk in front of Save-On Foods. For me, it’s Cherry Lane Mall, Penticton, summer of 2022. AD. For him, it’s Sumer 2022. BC.

As the rubber wheel hits the lowered curb, Professor Clay’s hat is caught in a gust of wind. He looks like a child who just saw a red balloon slip through his fingers and fly away. His mind is no longer like it was, and yet he’s supposedly the same person.

His mind is in fact six-fathoms deep in ancient lore. The End of Time: The Revelation of Gilgamesh, to be precise. This document has been hidden for 4044 years. In 2003 it saw the light of day, for 40 seconds, then sank back down into the bottom of the river of human knowledge. It now sees the light of day, for 40 seconds at a time, deep in the professor’s brain. It sinks back down, like the boat of Magilum, to the bottom of the Euphrates.

Professor Clay tells the middle-aged woman serving him coffee that he’s writing a scholarly book called The Vision of Magilum. She once cared for her 93 year-old grandmother, so she understands his state of mind. She gently asks, “Would you like cream and sugar with your coffee, dear?”

⏳

iraq, Spring 2003

The day was bright along the banks of the old Euphrates in the Spring of 2003. When Professor Clay saw the wooden shelves of the library he shouted out, yet no one heard him. No one in the archaeological crew had dared to remain in Iraq. As a result, no one heard him cry out slowly, in a gravelly voice like Moses himself, with his haggard face to the sun. No one heard him among the ruins of Uruk, and no one beyond him in the greater world cared. He was 30 kilometres from Samawah, and the guns of the armies were closing in. The world was going insane, again.

Professor Clay had lately started to wonder if he ought to be getting back to his family in Vancouver. The newspapers, such as they were, were full of misinformation, gloom, and doom. He called it boom and gloom and ulaloom.

Professor Clay had stopped reading everything but the headlines. He’d seen Colin Powell pointing to imaginary weapons of mass destruction, revving up the old machinery of war. He ought to have been pointing to something else beneath the sun-baked soil.

Everything the news channels said seemed meaningless, especially compared to what his crew had discovered two weeks ago: a cache of broken beams beneath a stone floor which no one thought to look beneath. After taking photos and measurements, they started to dig in earnest. As the security situation got worse, his understanding of the layout got better.

Two days after the last crew member flew to safety, he reached a layer of wooden doors, reeds, and stone masonry, all jumbled together, but in such a way that he could make out an entrance. Several metres further, but at the same depth, he found the wooden shelves. Shelf upon collapsed shelf crammed with clay tablets of hidden knowledge — a library!

Even if the worst befell the nearby cities, even if the fighting spread over the entire face of the desert, he would be there to save the tablets from the inevitable chaos.

So despite the approaching guns he persevered in dredging up the clay tablets from the Vault of Time. He became even more obsessed than he usually was. The treasures he was finding made all his previous discoveries look like trinkets.

He imagined himself beneath the stubbled ruins of Babel, beneath the great ziggurat of Etemenanki, where Ea, the god who smiled upon the human race, attempted to unify the many tongues:

Ea the wise lord of the land, shall change the speech in their mouths, so that the speech of mankind shall be one. — Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, 21st C. BC

The professor also thought of Borges’ “Library of Babel,” and wondered if he might find a tablet that explained the meaning of the library itself.

❧

Professor Clay had been resurrecting the forlorn script of cuneiform on and off since 1983, when he first came to Iraq. He had spent 40 years in the desert, with the sun god Shamash beating down on his raven locks (now grey) and on his soft white skin (now brown leather). He had made minor discoveries, but nothing like the tablets between the wooden shelves of this flattened library.

Next to the shelves he saw a large stone bin with dozens of short poems in it. The bin’s sturdy wooden legs had long buckled in time. Each of the poems was self-contained on a small tablet with a golden border. One read,

Youth, cold-sown in the fields of wheat

rises like warm bread in the light of her smile

Another read,

The aliens come like flocks of geese

and like gods they leave us

Like drunken poets, they steal our maidens

break the emptied vessels of our wine

and leave us staring at the fragments of their wit

On one of the larger collapsed shelves the professor saw a large tablet, which was cracked in two. It caught his eye because it contained the phrase, the boat of Magilum. The word Magilum was pressed deeper than the other words, and there was a crimson sediment in the grooves where the stylus had most deeply penetrated the clay. It was as if the word was pounded, not just tapped, into the tablet.

The word Magilum made him think about the passage in Gilgamesh where the great hero travels with his brother-in-arms Enkidu to the Cedar Forest to defeat the giant Humbaba, who guards the dwelling of the gods. In so doing, they might weaken the power of Enlil, the father of the gods. Or, at least, this is what Ea appears to have had in mind.

To calm Enkidu’s doubts about the peril of their mission, Gilgamesh tells him that when we die we sink into a meaningless oblivion, but while we live we can attain a meaningful glory:

All creatures will sit at the end in the boat of the West. When the boat of Magilum sinks, the creatures are no more. But we will go forward, fixing our eyes on this monster Humbaba. If your heart is seized by fear, throw the fear away; if you are seized by terror, throw the terror away. Seize instead the axe — and fight! Whoever leaves the battle unfinished is never at peace.

Professor Clay raised the upper portion of the tablet into the sunlight. It bore the title, The Sun at the Bottom of the River. It had a blood-red border, the same colour that was at the bottom of the grooves that spelt out the word Magilum.

The symbolism of the colour was uncertain, since blood could mean death but could also mean life. But what sort of life lay at the bottom of the Euphrates? He’d always understood the boat of Magilum as a symbolic precursor of existentialism and atheism. Along with the other grim Mesopotamian reports of the afterlife, the boat of Magilum seemed like a grim forerunner of Charon’s boat — yet without a landing on the other side!

The Mesopotamian boat suggested that we’d be better off in oblivion than flitting about like a shadow after death. This had always reminded the professor of Achilles’ words in the underworld: Don’t talk about the glory of the afterlife to me, bright Odysseus. By the gods, I’d rather be a slave on earth — the property of some dirt-poor tenant farmer — than be the king of the lifeless dead!

Professor Clay coined a phrase to sum up what he’d learned over the last fifty years of studying the Ancient World: Only in the present do we learn how much more we don’t know about the past. This saying of his held true once again: the newly-discovered tablet began with the words, Blood flows like life itself though the veins, and like a river to the sea. The next lines referred to the gangway, the ferryman’s warning, the cross-current, and the hidden stream, but the professor was still thinking about the meaning of veins and rivers and the sun setting in the West. Deep in thought, he looked at the ground. This is when he saw it, from the corner of his eye: a large unbroken tablet, bright as gold. Along the top it read, The End of Time: The Revelation of Gilgamesh.

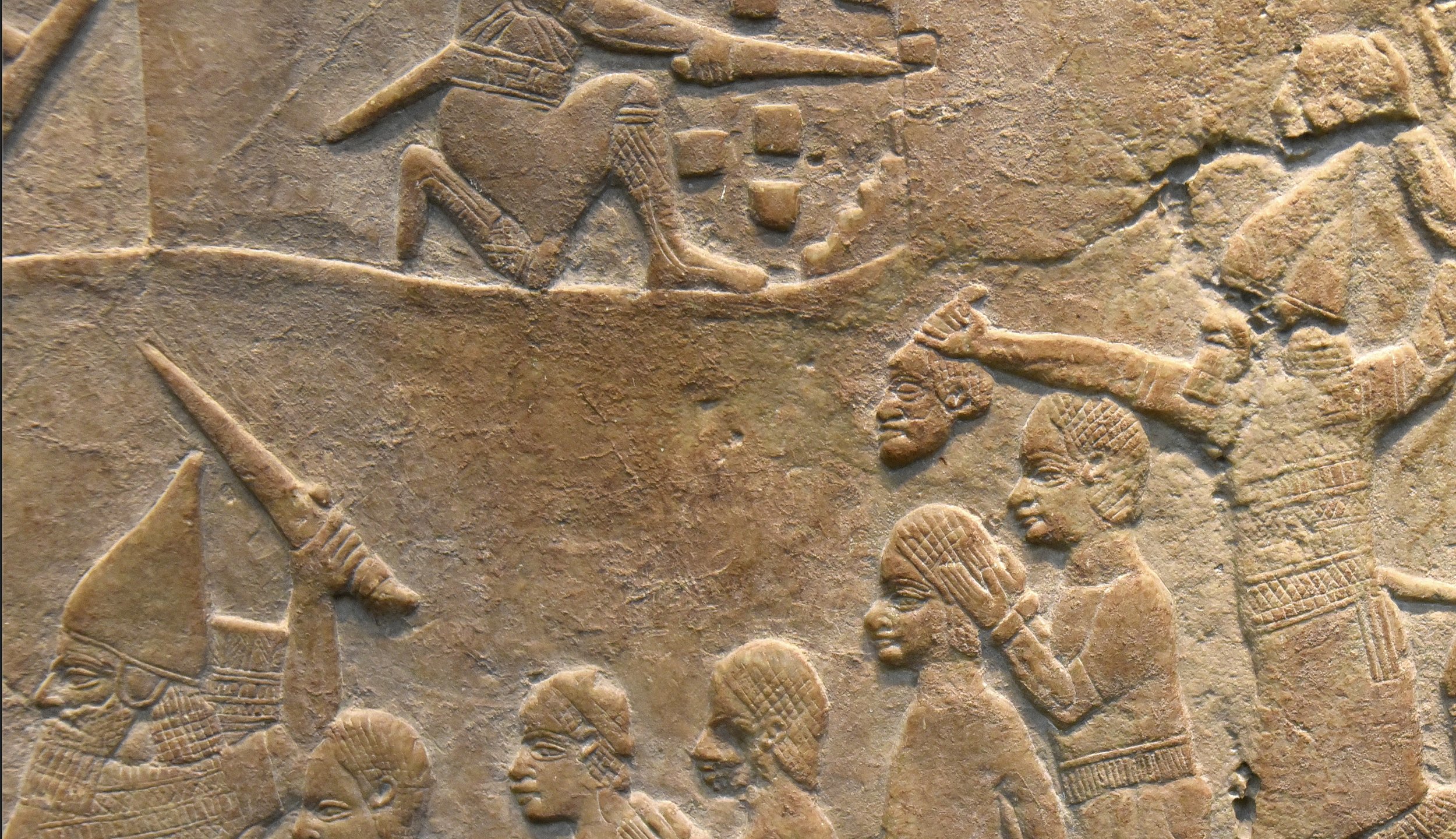

Professor Clay heard the engines overhead, the recent incarnation of the ancient engines of war. Umma and Lagash, Kish and Elam, the Babylonians and the Assyrians. No wonder the great god Enlil got tired of the human noise.

The words of Gilgamesh echoed in his head: Seize instead the axe — and fight! Whoever leaves the battle unfinished is never at peace.

He swore to himself that he would fight to make sure these ancient words would never be lost. And yet his spirit was sinking into the silty water as the bombs rained down on nearby Samawah and he could feel the explosions on the edges of the site. It was as if the fists of Humbaba, who guarded Enlil’s heaven in the Cedar Forest, rained down upon the naked shingles of the world. It was as if Gilgamesh and Enkidu were forever hacking the monster down.

Again and again the ax fell and the heads rolled. The professor took shelter under a nearby cedar tree, its thin branches giving him the illusion of safety. He looked down at the ancient words pressed into the clay more than 4000 years ago. The slashing script pounded into the professor’s brain:

The gold tablet with its black letters burned into the sockets of the professor’s eyes as the bomb fell that blew into pieces his right shoulder and the lower portion of the tablet as he sat on a rock in the slim shade of a cedar tree next to the hole in the ground.

The thunder-stroke erased the early layers of the palimpsest of his mind and his body fell backward like brittle clay onto the jagged earth. His mouth was parched, and he would give anything for a drink of water. Cold, sweet water.

Professor Clay lay on the hard hot ground between the rivers, until the whirring choppers came, and the medics, green and grey, whirled him away to his native land. As the chopper lifted off the ground, thunder-strokes destroyed what was left of the archaeological site.

⏳

Penticton, July 7, 2022

For nineteen years he’s replayed that moment when he sat on a rock in the slim shade of a cedar tree on the dry hot ground. He remembers a blue-green humming, a bright flash, and the tablet on his lap breaking into a hundred pieces.

The care-aid wheels him to a table in front of the window, where he replays moments 5 minutes and 15 years ago. He remembers the hat-string slipping through his fingers like the string of a balloon and he remembers another fragment: a dream about a raven sent forth from the Ark. It flies across the street and perches on the Save-On-Foods sign, as the rubber wheel hits the curb and his hat flies from his head like a balloon slipping from his hand. He looks up at the calm horizon and hears, far away, the thunder-strokes rain down on Kitsap and Minot, Uzhur and Ukrainka. The string slips through his fingers like water.

Everybody’s going about their business as if nothing is happening. There’s a pretty girl in a yellow halter top, ready for the beach. She opens the door of the cafe and looks over at me. I’m staring out the window, sitting next to an old man who is babbling about Uzhur and Ukrainka. As she waits for her moccaccino, she looks over the old man’s shoulder at what he’s writing in his bright golden notebook. It looks like a bunch of gibberish.

The care-aid manages to grab the professor’s hat in mid-air, and places it back on the professor’s head. His few wispy hairs are clamped back in place. And yet he feels the ground burning, and sees the sky turning red. Amid the dry shards and the broken reeds of his crumbling mind, he remembers a flash as if from a rocket, lighting up the bottom portion of the tablet. In the wild and crazy slashes of cuneiform, as if the scribe was writing while his hands were on fire, he sees the words, Exterminate the brutes!

The professor is still drinking his coffee, but the care-aid is impatient to get going. She needs to get back home before her kids get home from school. So she tells the old man to drink up, puts his cup in the recycling bin, and wheels him out the door.

⏳

river lethe, Date unknown

When they reach the other side of the street, the ferry-man takes two shekels from the old man’s shaking hands. Utnapishtim meets him on the shore and finishes his sentence: “Ea will meet us in the Garden.”

The professor sees a light blazing out, and in it is one whose grace and beauty are greater than the beauty of the world. Ea gives him water to drink and sets his feet on the ground.

—————

Notes

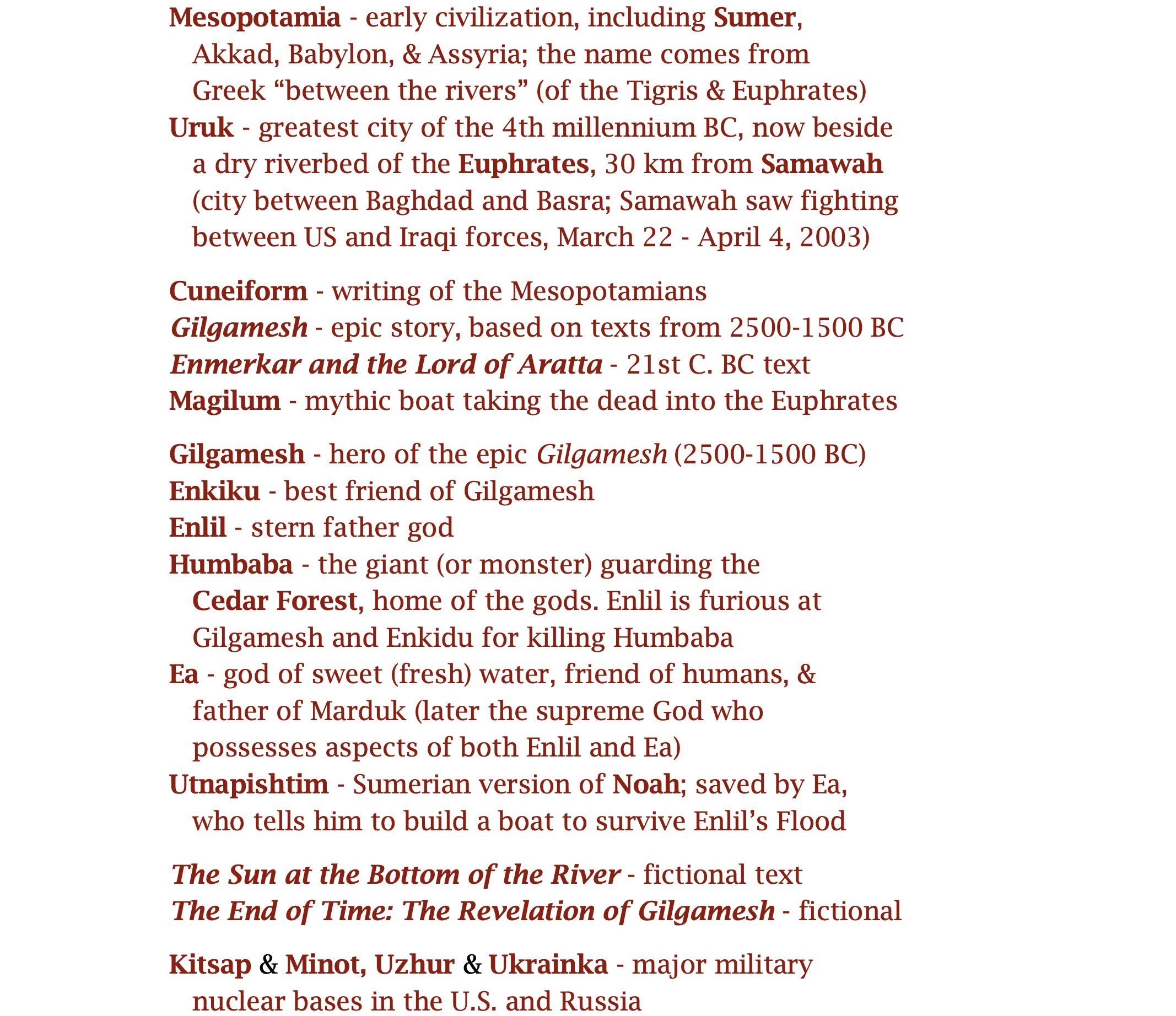

The old man in this story was once an Assyriologist, that is, an expert in Mesopotamian culture and the cuneiform language, which was used by the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, who all lived in the area of present-day Iraq from the fourth to the first millennium BC. Here are a few names that are important in the story:

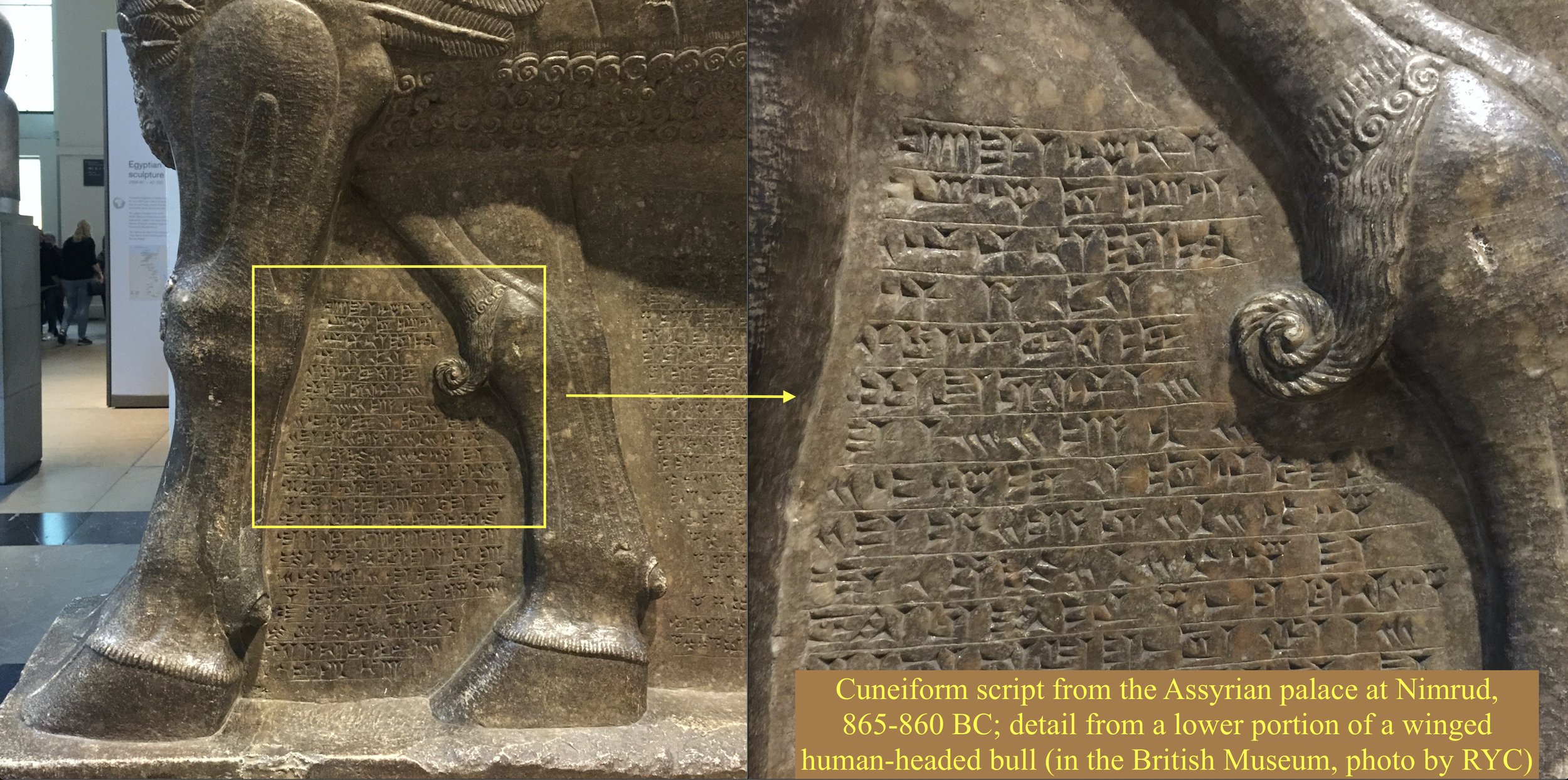

Cuneiform was written by using a cut reed to make imprints into clay tablets. This form of writing was standard for about 3000 years.

Cuneiform isn’t used today, and many cuneiform texts have still to be translated.

In my story the old Assyriologist was working in Iraq during the American invasion and suddenly found two cuneiform texts — The Sun at the Bottom of the River, which is about the boat of Magilum (the boat that souls board after death in The Epic of Gilgamesh) and The End of Time: The Revelation of Gilgamesh, which is an apocalyptic continuation of The Epic of Gilgamesh.

The story plays with the notion that there are probably many cuneiform texts yet to be discovered. According to the entry in Wikipedia, “Between half a million and two million cuneiform tablets are estimated to have been excavated in modern times, of which only approximately 30,000–100,000 have been read or published. […] Most of these have [not been] translated, studied or published, as there are only a few hundred qualified cuneiformists in the world.” What’s been translated so far, however, confirms that the Mesopotamians were crucial in the development of the most elemental aspects of civilization: numbers, letters, mathematics, laws, religion, technology, trade, and — unfortunately — war.

Cuneiform tablets also contain early versions of the Jewish story of the Flood, where God decides to inundate the Earth yet tells Noah to build an Ark. In one of the Sumerian versions of the story, the supreme father god Enlil is bothered by humans and decides to flood the Earth, yet the god Ea secretly tells Utnapishtim to build a giant boat. In my story, the god of sweet waters, Ea, plays a role similar to that of Jesus: he cares about humanity and he suggests a more compassionate version of the just yet stern father god.

The story of the Flood is found in various texts, one among these being The Epic of Gilgamesh, written in various forms between 2500 and 1500 BC. In this epic, Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu fight the giant Humbaba, who guards Enlil’s Cedar Forest, where the gods dwell. Gilgamesh and Enkidu are helped in their battle by the sun god Shamash.

My story is written in July 2022 AD. I suggest that the present war in Ukraine is a vague and distant echo of the warfare of Mesopotamian in 2022 BC — after the wars fought by Sargon and during a period of warfare between powerful cities.

One of the greatest Mesopotamian cities was Uruk, which dominated in the 4th millennium BC, but had declined by 2022 BC, in favour of other cities like Ur and Babylon. It’s in Uruk that Gilgamesh was a semi-legendary king, and it’s also in the ruins of Uruk that Professor Clay spends 40 years of his life on archaeological digs. In 2003 the area near Uruk and the present city of Samawah endured yet another war — this time between American and Iraqi forces — see Battle of Samawah (2003) in Wikipedia.

Just as the professor is making the greatest archaeological discovery of his life, he is blasted by a nearby bomb. He lives for the next two decades with a confusing and apocalyptic mix of cuneiform and biblical texts swirling in his brain. What he tries to remember — and finally succeeds in remembering, at the moment of his death on the sidewalk across the street from Save-On-Foods — are the lines from the two texts he discovered, before they were cracked in two and blasted to bits.

⏳