Gospel & Universe 🪐 Saint Francis: Pascal 3

God & Infinity

Infinity - Mathematics - A Sicilian Angel -Whitman’s Spider - Defining God - The Church of Infinity

∞

Whether or not we see God as infinity, or infinity as God, many of us long to be part of that infinity. There’s really no rush however: we’ll return to this infinity when we die. At that point, our lives and our thoughts will probably turn out to be less important than we thought. But all of that is speculation. What we know right now is that we’re alive, that the world is large, and that our time is short. As always, seize the day.

∞

Infinity

Pascals’ wager is a provocative piece of philosophizing. It’s initially appealing to skeptics because it suggests a detached rational framework, and it’s eventually appealing to believers because it uses this framework to dismantle the primacy of reason and to erect a theological framework in its place — which of course infuriates skeptics!

For agnostics the picture remains mixed. The use of reason to get at religion isn’t a problem. Rather, it opens up the range of human experience, levering the practical mind from a tight logic to an expansive emotion. Yet for the wager to be useful to agnostics, they need to divide it into two parts. There's a successful part that engages the mind philosophically and rationally, and then uses this to engage the mind in theological possibilities. Yet there's also an unsuccessful part that can be critiqued from numerous angles, six of which I looked at on the previous page. On this page I'll advance a more general critique centred around the notion of infinity.

Behind much of my argument lies the point I made on the previous page: Pascal's theological argument ignores the overwhelming range of theological possibilities. I'll leave the particulars of this point somewhat in the background here, and focus instead on two problems relating to math, definition, and infinity:

1. Pascal ignores the mathematical possibilities that lie between zero and existential nihilism on one side and the Infinity of God and salvation on the other, and

2. Pascal creates a logical problem by defining God in terms of infinity and then defining access to God in terms of a single, exclusive criteria.

My second argument doubles back to Pascal's odd theological choice that omits all but one theological option. The omitted choices might be divided into several types: theologies and philosophies he could have known about (Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, Stoicism, Sufism, early forms of Deism, etc.); earlier theologies he couldn't be expected to know much about (Hinduism, Daoism, etc.); and later mixes of science, philosophy, and theology that he couldn't possibly have know about (such as post-Lockean Deism, Romanticism, Transcendentalism, agnosticism, existentialism, etc.). While Pascal was forward-looking in his work on calculation and probability, he doesn't anticipate the agnostic possibility that one could doubt or disbelieve and yet still reach God. Those who speak specifically on God’s behalf — telling us what He is, how He works, and who He will or will not save — don’t seem to share the following agnostic assumptions: we’re far too limited a species to grasp what God is or how He/She/It operates; the most respectful definition or characterization of God we can entertain is a benevolent Infinity; and any limits we place on such an Infinity are presumptuous.

∞

Mathematics

My first argument involves mathematics, an area in which Pascal excelled, having invented the first calculator and having more or less inaugurated the study of probability. It may seem terribly presumptuous for me to critique Pascal in relation to mathematics, given his invaluable contributions to the field and my very rudimentary understanding of it. Yet my argument isn’t based on the theories and intricacies of math, but rather on a disconnect between a basic mathematical concept and the theological argument he makes. In this sense Pascal's expertise in math makes his wager all the more odd — and all the more difficult to accept.

∞

Generally, when one thinks of our numbering system (at least since the Hindus and Arabs had anything to do with it), we start with zero. To the right of zero we imagine fractions and then whole numbers, till we reach a hundred, a billion, a sextillian, etc. After about an hour of writing zeros, we see that this exercise can be carried on indefinitely. At this point we can better grasp the concept of infinity.

The possibilities that lie between Zero and Abstract Infinity are, in mathematical terms, infinite, yet in arguing about theological belief Pascal contracts this infinite world of possibilities. Worse, he all but erases it in his final choice between a meaningless zero (and all the negative numbers to the left of the decimal point) and a meaningful positive Infinity (which lies beyond all the numbers on the right of the decimal point). How could such a famous mathematician as Pascal leave out all those never-ending numbers between zero and infinity?

∞

Pascal equates his God with infinity, yet if God is in fact master of the numbers great and small, it seems perverse to insist that however great the beauty and design of these numbers (which stand for everything in the universe), we must discount all of this beauty and design. We see Pascal’s arrière-plan or background reasoning in a fragment of his Pensées in which he argues that each of us is an infinite abyss, a gouffre infini that can only be filled with the infinity of God:

What else does this craving, and this helplessness, proclaim but that there was once in man a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him, seeking in things that are not there the help he cannot find in those that are, though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself.

Qu’est-ce donc que nous crie cette avidité et cette impuissance sinon qu’il y a eu autrefois dans l’homme un véritable bonheur, dont il ne lui reste maintenant que la marque et la trace toute vide et qu’il essaye inutilement de remplir de tout ce qui l’environne, recherchant des choses absentes les secours qu’il n’obtient pas des présentes, mais qui en sont toutes incapables parce que ce gouffre infini ne peut être rempli que par un objet infini et immuable, c’est-à-dire que par Dieu même. (du fragment Souverain Bien 2)

Pascal’s point is an ingenious one, and would appeal to many Romantics and Transcendentalists, yet it’s also a case of reasoning from two extremes. Moreover, our great cravings are all the more reason we would marvel at the great beauty of the world and universe, as well as at the near infinite range and complexity of designs, from atoms to the geometric precision of a spider's web or computer chip, and from the human brain to the images coming to us now from the James Webb Space Telescope.

∞

A Sicilian Angel

A decade ago I bought a little glass angel in the picturesque town of Taormina, with it’s Graeco-Roman theatre perched on the gorgeous Sicilian coastline:

The angel I bought there makes me smile whenever I look at him.

He seems so perpetually surprised by the grandeur of the world around him, as if he’s been traumatized by the beauty of the contours of Taormina’s amphitheatre — how smoothly its half-circle fits into the jagged coastline.

Did the pagan world really do this?

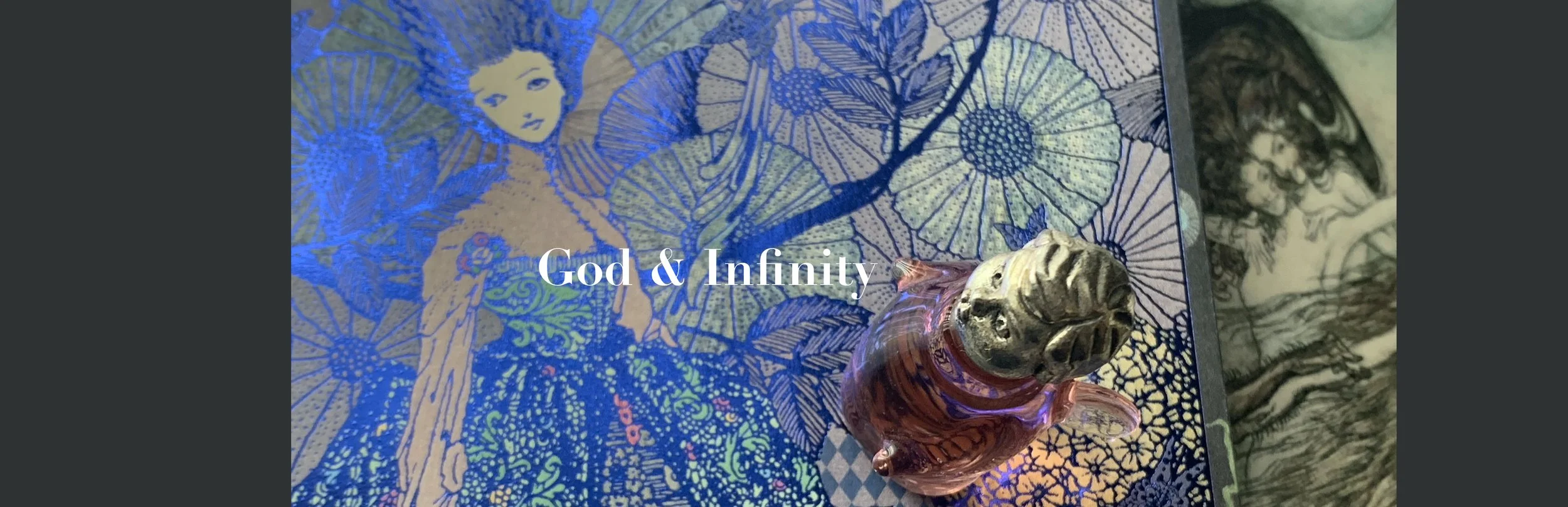

Back in Vancouver, I set my little Saint Francis down on two book covers and take a photo. Here he stands, hollow-eyed and amazed, on a Rackham & Clarke wonderland of flowers and waves:

Petrified in space, Saint Francis marvels at the beauty of the woman’s dress. He’s an angel, used to all kinds of shimmering glory. He knows that God’s world “will flame out, like shining from shook foil,” yet still he finds it difficult to look at its human incarnation in the form of a woman who isn’t the Mother of God.

He averts his eyes from the lush panoply of flowers and woven stuff that might tempt his eye upward to the contours of the head that’s set on an angle on its long neck, and at the hair that combs out, like the flowers fanning outward. The space around her eyes shimmers so intensely that he can’t look at it directly. So he stares up into the air instead.

He hears the sound of the sea behind him. He doesn’t dare turn around to see the spray splashing up the arms of Rhine maidens who have wandered far from their northern homes.

∞

Whitman’s Spider

Pascal’s infinite abyss, his gouffre infini, reminds me of a spider swinging in a meaningless void, yet agnostics see our essential nature more in terms of an open, explorable, infinite space, an espace infini. Some agnostics might see this infinite space as negative, yet the more negatively they see it, the more they become nihilists and the less they become agnostics. Following Huxley, agnostics tend to see our existence amid infinity as an opportunity to explore, to experience, and to communicate with other beings or realities. In this they are similar to Whitman’s spider, who is isolated in measureless oceans of space, yet is forever seeking the spheres to connect them:

A noiseless patient spider,

I mark'd where on a little promontory it stood isolated,

Mark'd how to explore the vacant vast surrounding,

It launch'd forth filament, filament, filament, out of itself,

Ever unreeling them, ever tirelessly speeding them.

And you O my soul where you stand,

Surrounded, detached, in measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form'd, till the ductile anchor hold,

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere, O my soul.

Curiously, Whitman wrote this poem in 1868, around the very time Huxley was consolidating his ideas about agnoststicism.

∞

One can see Pascal’s wager in a positive light, as a way of opening a mind that's trapped by logic into believing there can't be any overwhelming meaning in the universe, and that there can’t be anything mystical or supernatural. Yet if his wager is used as a way to present two choices that are mutually exclusive, it presents a false dichotomy, one that forces the world into believers and nonbelievers. This frustrates rational people who can’t see why they must boil the infinite world of numbers down into an abyss of nothingness, simply because each one of those numbers isn’t the abstract concept and the impossible number we call infinity.

Why should we boil this world down at all? Why should we look at its variety — its numbers large and small, intricately patterned by sequence, formula, and algorithms that stitch its magic across the overhanging firmament — and call it nothing? How can Pascal say that just because we don’t make a specific theological choice we lose it all?

How could he imagine, crossing in his mind the aeons of time — the vast field of extrapolations, the interconnected transmuting ocean of almost infinite variety — that only one formula functions throughout all of the varied sequences, that only one spiritual path cuts over the sea?

∞

Defining God

The second problem with Pascal’s idea that you lose everything if you don’t bet on God is that it expresses a view of God that is at odds with the most fundamental definition of God. Almost universally, religions define God as the ultimate, highest, most complex, benevolent, and just force in the universe. Given that this definition operates on superlatives that are complements to Infinity — omniscience, omnipotence, eternity, and ineffability — it doesn’t make sense to say that one religion has a monopoly on the understanding of God or that one particular path is the only path to God. If God is so much greater than we are, how can we circumscribe Him? How can we ascribe a gender, let alone a modus operandi of preferential treatment and specific cultural norms?

This should be obvious in Christianity, which assumes that humans are very limited in their vision, deeply flawed at best and miserably sinful at worst — in either case completely unqualified to understand God. Pascal himself makes a powerful point about this, arguing that we exist in such a dark abyss of ignorance that we can only be saved by God’s infinite light: "this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object; in other words by God himself / ce gouffre infini ne peut être rempli que par un objet infini et immuable, c’est-à-dire que par Dieu même." So how, if we are an infinite abyss, can we know what God is thinking and how He would save or not save any given individual? More specifically, how can we know that the Bible and Catholic doctrine are right — let alone the only Only Truth — if we are so steeped in darkness?

This problem lies at the heart of all dogmatic thinking, and it’s the very point agnostics make to those who think they know everything. Agnostics avoid trying to sound like Socrates — plying each statement to reveal its partiality, its fatal error — yet they assert that we are far too limited to understand the essence or totality of existence. An agnostic doesn’t say Pascal is wrong for believing in God, or for believing that his form of God and his way of being religious aren’t right for him. Rather, the agnostic observes that Pascal has no logical grounds to speak for God, or to tell people who believe in God differently — or not at all — that they’ll miss out on eternity (and many preachers would add, be cast into the smouldering flames!) if they don’t believe in a particular version of religion.

A more reasonable, charitable, and inclusive approach would be to say that God’s infinity could touch everything, whether it’s an animal, an inanimate collection of things, a person who is questioning, or a person who doesn’t see how God can be limited to one timeframe and to one specific philosophy. It’s ironic that those who believe in God tend to limit God’s relation to the universe, whereas free thinkers and agnostics leave the field of God’s influence open-ended, steeped in the mystery of infinity.

Agnostics have no interest in saying there's no God, yet they also have no interest in saying that God only works in certain ways. Rather, agnostics would say, Perhaps God works in mysterious ways. But to say that someone who's thinking openly and freely loses everything — that they're cast out of all joy, bliss, beatitude, paradise to come, or whatever it is that the universe has in store for them — is to limit the charity, tolerance and grace of God. Which, again, contradicts the very definition of God.

∞

The Church of Infinity

If asked to give their definition of God, agnostics would say something like, 1. God is one very inadequate name for the Force that reigns over space and time, 2. we don’t know the motives, meanings, or goals of God, although the vast stretches of astronomy, the intricate organization of physics and chemistry, and the human experiences of love and art give us a sense of what these might be. Given this definition, agnostics have difficulty making specific claims about God, and they remain skeptical of those who vehemently deny the existence of God or who advance exclusive definitions of God. A definition that works fairly well for them is God equals Infinity. Period. Without a qualification or a creed placed on top of infinity. They don’t even need to capitalize it, as if God as Infinity would be offended by a small i. As if catholic wasn’t more inclusive than Catholic.

Given that agnostics live in a world of math and numbers, they couch their elusive creed in universal terms. They don’t say, You must do this and You must do that, and they almost never say, You can’t do this or You can’t do that (unless it’s murder, theft, or some other crime covered by secular law). They’d leave that to infinity, or to Nature with a capital N, or to what they’re happy to call God — as long as It/He/She remains elusive rather than exclusive, loving rather than jealous, fraternal rather than despotic. They don’t require that you think heavenly thoughts or believe certain theological narratives. Rather, they suggest that we move in the direction of greater numbers, openness, and empathy.

Agnostics don’t doubt that two plus two equals four, yet they observe that two to the power of two billion equals so much that we can’t imagine it in any concrete, specific way. Even the most enormous computer isn’t large enough to contain an infinite sequence of numbers. It has to code or signify infinity in a discreet or limited way, as in the letter eight tilted at ninety degrees: ∞. It doesn’t matter if it’s tilted from the left or from the right, or if it’s written with a progressive or a conservative hand. Every thought, emotion, and experience falls into it, and falls forever.

Agnostics can only hope that salvation or ultimate truth lies in the concept or symbol of infinity, which is ungraspable, unbreakable, and ineffable — like God. In the meantime, they would suggest that the more variety we entertain, the more sequences of love and understanding, and the greater possibilities that we add to our never-ending calculation, the closer we come to realizing how much larger God must be than we can ever imagine. It’s the direction that’s important, not the specific value, characterization, or narrative we give to infinity.

As for religious practice, agnostics would refer people to the time-honoured moralities of humanity, from the 3rd millennium BC code of Ur-Nammu to the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They would suggest that everyone read John Stuart Mill’s 1859 tract On Liberty, which argues for extensive personal freedom reinforced by respect and accountability. Other than that, agnostics would counsel something like the following: As you follow your path, finding its beauty and danger, remember that there are other paths just as beautiful, and just as dangerous. Some tempting paths ought to be followed, others avoided. You choose. There is a time for everything: a time for love, a time for compassion, a time for action, and a time for walking in the forest and coming upon five roads that diverge in the yellow woods. There are a trillion times a trillion choices, not just one. Remember this when someone tells you that you must choose between one specific belief or nothing. There are an endless number of ways that lead to the impossible destination, the concept that lies beyond all numbers and words: ∞.

✝︎

Next: ✝︎ Pascal 4: Zhuangzi’s Pivot