The Double Refuge 🔭 The Sum of All Space

Third Spinning Rock from the Sun

Jet Lag 1 - Copernicus: Location x Location x Location - Moses: The Moving Sky

🔭

Jet Lag 1

We’re moving at hundreds of kilometres a second in different directions. Yet here I sit in front of a marble table that appears to be absolutely still.

It’s 4 AM and I’ve got jet lag. After tossing and turning in a sort of sleepy wakefulness (or wakeful sleepiness), about five minutes ago I decided to just get up and have a coffee.

I turned on the lights, and thus activated a flow of electrons that I don’t really understand. I then put coffee beans, which came from somewhere in the highlands of Ethiopia or Columbia (I’m not sure which) into a metal container and closed the lid. I pressed a button and three razor-sharp blades spun amid the coffee beans, creating a noisy havoc of tiny brown bits. Thirty seconds later, I put a small cup of espresso on a white marble table next to the living-room window.

Outside the window a patch of pale light is widening slowly in the blackness. I take my first sips. The table’s moving at hundreds of kilometres a second every which way through the universe. And yet it appears to be perfectly still. There are no strong air currents in the room, so the surface of the coffee appears to be absolutely flat.

A still cup of espresso on a marble table at 4 AM. What could be more magical, more mysterious than that?

🔭

Copernicus: Location x Location x Location

In 1543 Copernicus wrote, At rest, however, in the middle of everything is the sun.

He was of course wrong.

He was right about the sun being in the centre of the solar system. The Church, for a thousand years, was wrong about that. Yet only from the most human-centred perspective can the sun be thought of as in the middle of everything. And it’s certainly not at rest.

At its equator, the sun rotates at about two kilometres a second. A seething mass of plasma crisscrossed with magnetic currents, the hydrogen and helium in the sun move in different directions and at different speeds. Nor is the sun stationary in the larger space that surrounds it. With its eight planets, the sun moves around the centre of the Milky Way at over 250 kilometres a second. This is like going from Vancouver to Calgary, 674 kilometres, in less than three seconds. The flight usually takes an hour.

The Milky Way, with its 100-400 billion stars, is unbelievably big. Yet it’s like a drop of water in an ocean, the currents of which are still being charted.

The Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy (the largest nearby galaxy) are being pulled at over 100 kilometres a second toward each other by their own gravities. They’ll collide in about 4 billion years, to create a new massive galaxy.

The Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxies are the largest galaxies in our Local Group of galaxies, which lie on the edge of the Virgo Supercluster of galaxies, which is moving toward the Norma Cluster and the Great Attractor at about 600 kilometres a second. Travelling at 600 kilometres a second, one could get from Vancouver to Calgary in just over one second. The Great Attractor is itself moving toward the Shapley Supercluster, an extremely dense region of space in the Centaurus constellation.

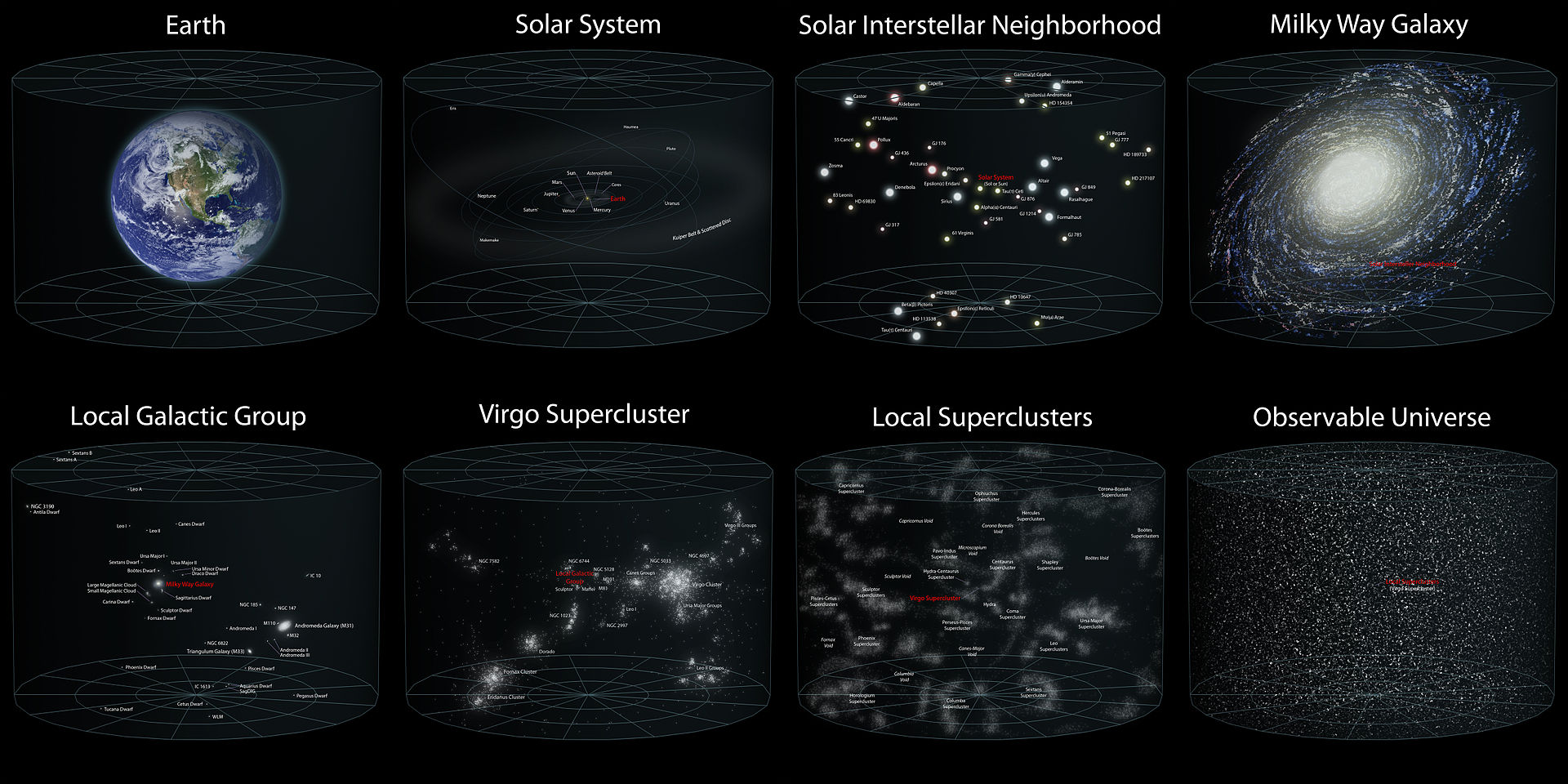

The following two maps show our Local Group (in blue to the left of the Virgo Supercluster) and then the Virgo Supercluster (in blue to the left and below the Centaurus and Shapley superclusters).

The Laniakea Supercluster appears to be the largest rotational or gravitational dynamic we’re involved in. I don’t pretend to understand the ins and outs of astronomy. I am, after all, an English teacher. I understand Voltaire’s clock-work God better than Newton’s gravity. Yet as far as I can see, our greater movement through the universe may depend on 1) whether or not there are gravitational walls or dividers between super clusters, and 2) whether or not super-clusters, groups of super-clusters, and perhaps the universe itself, are within larger rotational or gravitational systems.

Here are two charts of the universe from Wikipedia showing where we appear to be in the larger dimensions of space. The charts are very large and detailed; enlarging them is a mind-blowing exercise in cosmic awareness. The first chart below is no longer on the “Universe” page of Wikipedia, yet the second one can be reached by clicking the graphic (if your computer can handle it, choose the version in 4,500 × 3,294 pixels).

At present, astronomers think there are about 170 billion galaxies, and about 300 sextillion stars — that’s 300, 000, 000, 000, 000, 000, 000, 000 stars. If history’s any guide, better technology will reveal more galaxies and more stars. Indeed, it was only in November 2013 that astronomers discovered the Hercules-Corona Borealis Great Wall, a super-cluster of galaxies 10 billion lights years wide. This star wall can be seen on the top right of the Local Superclusters chart above.

Who knows, what we now see as the observable universe may be moving toward another universe, which may be rotating around a more distant cluster of universes. A hundred years ago we didn’t even know there were other galaxies. In the 10th Century the Persian astronomer Al-Sufi called the Andromeda galaxy a small cloud, and in the 18th Century Thomas Wright speculated about separate galaxies, which Immanuel Kant called island universes. Given that it wasn’t until the 1920s that Curtis, Öpik and Hubble proved the existence of galaxies, who’s to say that what we now call the universe isn’t just one among many? Whatever space you can see or verify, you can always imagine a space outside that space. Who knows, we may be moving a million kilometres a second, toward who knows where. In The Outer Reaches, I make a more detailed — yet still very speculative — case for infinite space.

🔭

Copernicus made invaluable contributions not just to science, but to our understanding of philosophy, religion, and space itself. Yet when he wrote, “At rest, however, in the middle of everything is the sun,” his judgment was clearly premature.

🔭

We’re also moving at incredible speeds within our own solar system. The earth’s rotating at about 30 kilometres a second around the sun. Again, it’s difficult to imagine this type of speed. Traveling 30 kilometres in one second is like going from downtown Vancouver to the Vancouver International Airport — past a hundred cross streets — in a third of a second. Imagine that you’re flying past chairs and doorways, street signs and trees, open fields and over baseball diamonds, in the blink of an eye. You fly past all these in the time it takes you to say Wo. You don’t even have the time to say Wow! Nor can you see the things you go past. It’s all a blur — unless you’re a dozen kilometres in the air, in which case you’re too far up to make out any detail, apart from things like a shopping centre or an airport runway.

At the same time we’re orbiting around the sun, we’re also spinning on our axis at about 500 meters a second (at the equator). At this speed, you could perhaps see a baseball diamond, but you wouldn’t have time to see who’s playing.

🔭

Moses: The Moving Sky

Moses lifted his eyes from the ground and saw that everything moved: the winds twisted and the sky wheeled, with its piercing yellow ball from one end of the horizon to the next.

But the ground stood absolutely still. The sand dunes of time drifted this way and that, but the ground beneath them didn’t shift.

More constant than the great sun-god Ra, the deep stone edifice of Earth was deeper than oceans, more solid than the god-filled sky.

Moses lowered his eyes to the ground and saw that it didn’t move.

🔭

Next: Of Sand & Salt