Gospel & Universe 🔭 The Sum of All Space

Dogma & the Stars

Dogma - A Convenient Narrative - Jet Lag 2 - Notes and Scales

🔭

Dogma

Many Modernists left behind the Medieval vision of the whole truth and nothing but the truth. They realized that a literal interpretation of the Bible no longer explained their location in the universe or their condition on Earth. Some went on the attack: in his 1879 preface to Destroyer of Weeds, Robert Ingersoll mocks Medieval religious claims: There was a time when a falsehood, fulminated from the pulpit, smote like a sword; but, the supply having greatly exceeded the demand, clerical misrepresentation has at last become almost an innocent amusement. Others put their focus on the positive things said in sermons — things that resonated with conscience, charity, forgiveness, love, and the possibility that the universe was controlled, and made meaningful, by a loving God.

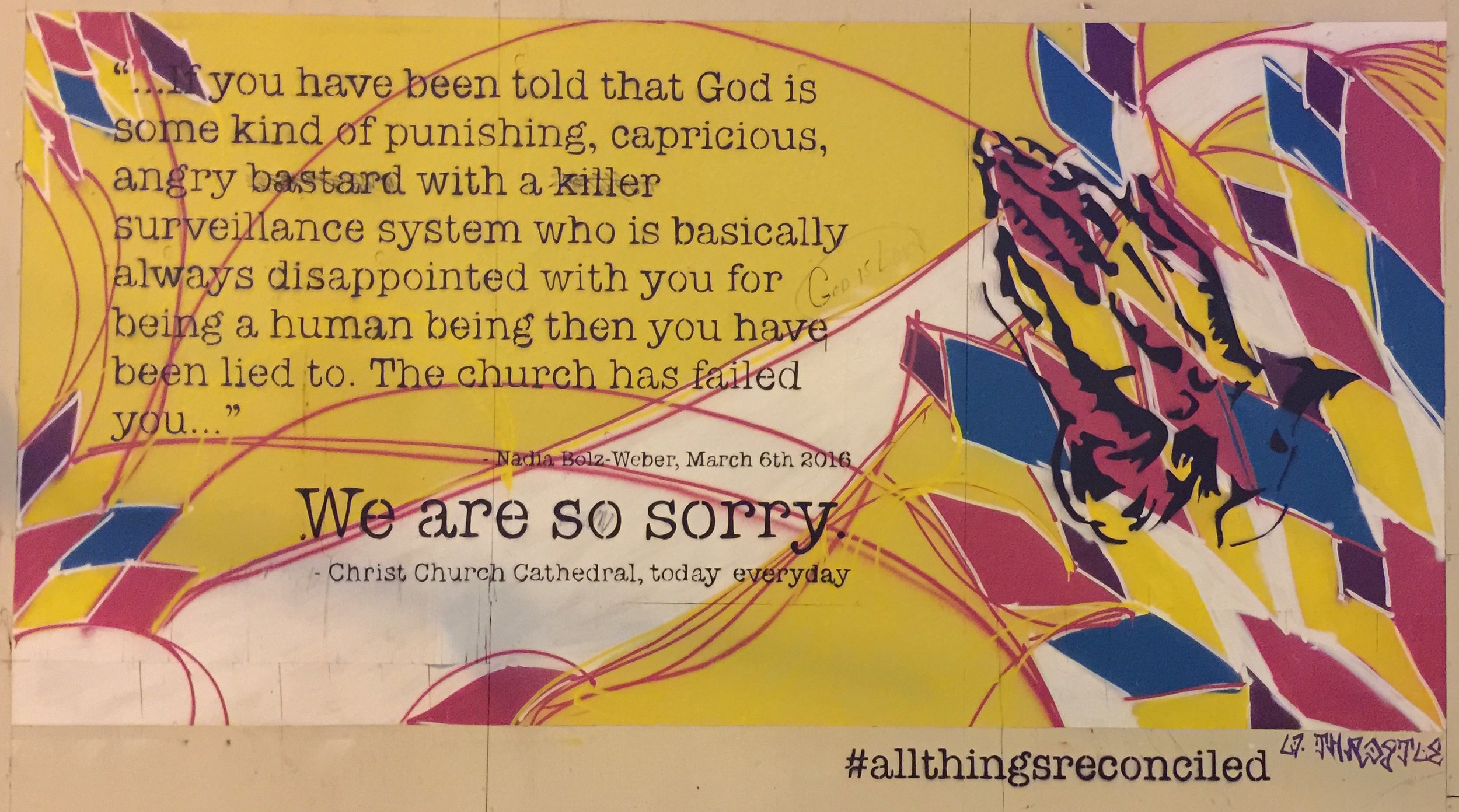

The other night I was walking home from downtown Vancouver and saw this poster. It was pasted onto a temporary construction wall around the Anglican Christ Church Cathedral:

The Bible and tradition has put rational Christians in a tight spot. They have to square what they read in the Bible and what Christians have done in the past, with what they really want from Christianity: love & charity. Not wanting to reject the possibility of God, many Modern Christians are wary of rejecting the quasi-historical framework that has nurtured this possibility for a thousand years. This means that in order to retain the loving spirit of Jesus, they feel obliged to retain, or reconcile themselves to, the dogma that has accumulated around him, as well as the angry, partial, fire-and-brimstone utterances of the Old Testament God.

Many find themselves in a difficult position: Think for yourselves, yet don’t question the authority of the Bible, the Jewish God, or the gospel account of Jesus. Many decide to follow Martin Luther, who in the early 16th Century urged people to think for themselves, yet urged them not to doubt the Great Truths of Christianity. Hence the Lutheran justification: By grace alone through faith alone on the basis of Scripture alone. Yet this formulation presents us with a bizarre version of seeking truth: find truth, but make sure that you find The Truth. Understandably, many people from Christian cultures revolt against this predetermined path to truth. It just doesn’t make sense to open your mind and close it at the same time. As a result, many turn to philosophies that don’t so vehemently ignore history or science: atheism, agnosticism, ecumenicalism, Romanticism, Transcendentalism, Unitarianism, Taoism, etc.

Others choose an in-between option, taking pieces from their old faith and reworking them into a new whole. Tom Harpur is an interesting case in point: he subordinates Medieval Christian ideas to a spiritual Myth that’s more widely historical and cross-cultural. Harpur’s Christ Principle incorporates earlier myths and religions, especially those of Egypt. He uses these to create a new, pagan version of Christ.

🔭

A Convenient Narrative

I’ve been reading Tom Harpur lately. It’s a relief to read that Jesus, in whom I could never quite believe, probably never existed. It’s enlightening to find that, instead, Jesus is a Deep Myth from the earliest civilizations. He’s a Myth that's truer than dogma. And, I feel compelled to add, a Myth that’s truer than fact.

This is the problem I have with Tom Harpur. He says that the traditional version of Jesus is an unbelievable story, and that we need to dig deeper, to a story we can believe in. He even quotes Joseph Campbell: Myth is what never was, and always has been. This is very liberating, especially if you’ve been born into a traditional Christianity, but have never felt at home there. But it’s also a very convenient narrative. It presupposes an always has been that I doubt ever was.

It’d be wonderful if at the deepest level all the old myths about the soul and the Cosmic Spirit were true. But what’s meant by true? That they’re wonderful stories that we hope to be true? That’s easy to believe. But does it also mean that they’re in some sense truer than that? That they connect to some deeper stratum of consciousness, sub-consciousness, or supra-consciousness? That they’re part of a spiritual nexus or Noösphere? To affirm the truth of Deep Myth is to make a leap of faith that’s at once different from, and yet similar to, the one traditional Christians ask you to make. It liberates you from the Mystery of the One, yet puts you face to face with the Mysteries of the Many.

🔭

Jet Lag 2

It’s 4 AM and I’m looking at the cup of espresso on the white marble table.

Rosy-fingered Dawn is slowly drawing Night’s mantle from the cobalt sky. A bough, with its light green buds, moves gently in the wind outside my window. The tree has reached up seven stories into the sky to present its buds to the sun. It has waited twelve hours, quietly in the dark.

Yesterday I sat at a café eight and a half thousand kilometres away, watching the boats bob and clink in the harbour of Marseille. Eight hours ago I was on a plane. The surface of my coffee vibrated slightly on the fold-out tray, tiny ripples rippling outward from the centre of the cup.

I watched the movie Gravity on a little screen. The Lufthansa jet flew at about 200 meters a second. Ten kilometres below it was the Atlantic Ocean: 323 million cubic kilometres of salt water. 323 million cubic kilometres.

The jet circled within the gravitational pull of the earth, which circled within the gravitational pull of the sun, which circled within the gravitational pull of the Milky Way, which hurtled within the greater pull of a cosmic mystery.

As I sit at the still table in front of me, the pink light of the sun turns yellow and white, all according to the way the molecules of the atmosphere filter the incoming waves. I think of astronomy, biology, and the human spirit that tries to fit the pieces together.

🔭

Notes and Scales

A cave man bangs out a harmony

with a dry femur against two bearskin drums,

singing of the stars and moon.

The Daoist master teaches his students, in absentia:

all they see are his footprints

leading upward into the snowy hills,

pine boughs buckling beneath the weight.

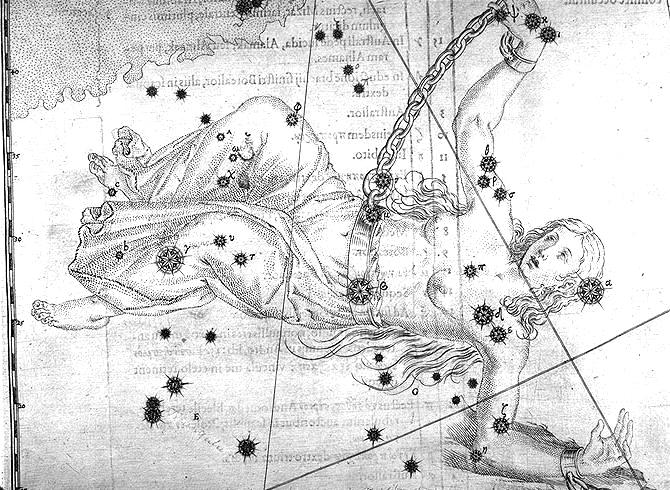

Aristarchus looks up into the Greek sky, wondering if that really could be Diana with her bow, or Andromeda on a rock.

The astronomer adjusts an angle on one of the 115-tonne antennas and peers into the centre of the Milky Way, past the anarchy of swirling suns, wondering if what lies in the middle of it all is in fact a supermassive black hole.

He shudders to think that this is only one of hundreds of billions of galaxies.

He shivers in his lab coat, though the room is warm in the ALMA Observatory, five kilometres above the Atacama Desert.

Along thin, brief lines of human time we connect the dots.

🔭

Next: 🔭 The Chinese Sky