The Ring 💍 Paris

The Academic

What, Martine thought to herself, could humans possibly know about the nature of reality? They spent a third of their lives sleeping in their beds, dreaming nonsensical dreams about whatever ridiculous things they’d done during the day. And then they spent half their waking hours thinking about what everybody else was thinking. They built up a body of knowledge that they called science, and then proceeded to ignore all the other bodies of knowledge that they’d built up for the last 4000 years. They ignored the wisdom of the past, and then complained that their lives were meaningless.

The only humans that made any sense to her were the artists who broke all the rules and the academics who dug up what people had forgotten over the years. She was especially fond of the dearly departed Assyriologist Jean Bottéro, who tried to explain (despite resistance from priests and pastors) that neither the Greeks nor the Phoenicians invented numbers and writing, and that neither the French nor the Danes invented existentialism. Martine’s uncle François told Martine about Bottéro’s Monday afternoon seminars, which he gave after retiring from the École Practique des Hautes Études. François taught Egyptology there, and was fascinated by his colleague’s take on the sister-civilization on the other side of the Red Sea. She listened to her uncle, with a sort of otherworldly rapture, as he told her about the struggles Jean had with the orthodox establishment, and yet how he ploughed through all of this to uncover the implications of the ancient Sumerian and Akkadian texts.

François told his rapt niece about the 4000 year old tablets which contained the story of Gilgamesh, the king who tried to find the land of the afterlife, where he might see again his dear friend Enkidu. On his quest, Gilgamesh meets an alewife, who tells him that there’s no such land. Nevertheless, Gilgamesh finds a ferryman who steers him to the paradise of Dilmun. Here he finds Utnapishtim, who was told by a god to build an ark in order to survive the coming flood. Yet, unfortunately for Enkidu and Gilgamesh, this survival business isn’t for humans. Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh that no other humans — other than him! — get to live once the waters of death have covered their heads.

With a twinkle in his eye, François called Gilgamesh the ur-text and the genesis of the later sacred texts, from those of Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon to Borges’ “Library of Babel.” François added that Gilgamesh was also the starting point for the strange journey of religious mutations, which took humanity from religion without an afterlife or cosmic Plan, to religion with a detailed topography of Heaven and Hell. At first, death is a slow descent into water, or a scrabbling among dusty feathers, but later it becomes a very specific doctrine about Heaven and Hell, and about what you have to believe in order to get to one and avoid the other, and about what a wafer in the mouth means if the man who has this wafer in his mouth speaks certain words in Latin or Greek.

Her uncle had been a great help guiding Martine through her early school years, where the teachers were really good at throwing alienating philosophy at their students, yet not so good at suggesting how these philosophies might bring her life together in some meaningful way. Yet like Bottéro, François had read his Voltaire: when the wise alien Micromégas gives the French Academy a book that contains all the answers to life, the old secretary see that it contains nothing but empty pages. Commenting on Voltaire, François told his niece the same thing that philosophers from Locke to Sartre had said: “The only thing to do about the human condition is to fill those empty pages with something interesting. If you’re a blank slate, then you have the freedom to inscribe what you want. Engrave something beautiful into the surface, even if you do it like your beloved William Blake, with corrosive acids and crazy speculations.”

Because Martine thought like an alien, and because she wrote with acids and crazy speculations, she made the perfect academic. Out there in the world, most people were practical. But within the narrow and convoluted corridors of the Ivory Tower, with its intricate marble balustrades and its occult libraries leading to dream-chambers that would put most people in the looney bin, her type of thinking didn’t seem strange at all. So she continued to play the game, and no one was the wiser.

💍

Sitting, waiting, Kenneth thought about Martine. And because he wanted her to be there and she wasn’t, he also thought about Antoine.

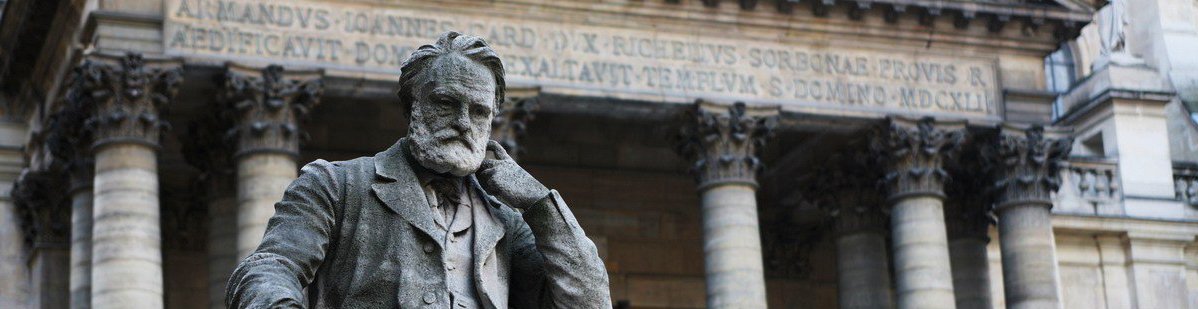

How he hated the man! It irritated him to see Antoine ride up to the curb in front of the Sorbonne on his mobylette. Antoine always wore tight black leather pants, so thin you could see his penis pointing more or less upward. Kenneth called it the Leaning Tower of Penis. Antoine also wore the same tattered collection of Serge Gainsbourg t-shirts every day, as if he were a poor student instead of a professeur agrégé at five-thousand euros a month. He strutted in front of his students like a metrosexual peacock. He spouted ridiculous theories about the relevance of Japanese cartoons and the music of Lady Gaga — anything to ingratiate himself to the latest fads and the slimmest legs. It would have made Victor Hugo vomit.

Kenneth also hated the way Antoine wore his beret tilted on his rich, dark hair. Could he be a bigger stereotype, a bigger show-off? The beret was cocked to one side, as if he were about to paint a lily pond in Giverny. He was a walking, scootering caricature of a French bohemian, a baby bobo, wrapped in tight leather.

And of course Antoine’s favourite restaurant was this cursed Maison de Verlaine. Its dark corners were hidden from street view and its table-cloths draped onto your knees, so that you couldn’t say where a leg stretched accidentally or where a hand glided beneath the folds. He hated the whiteness of the cloth napkins.

He imagined Antoine catching mid-air a splatter of whipped cream that flew from Martine’s fork, frustrated as she was at having to pretend to be interested in his Japanese comics. These were the same pink and blue comics that Antoine gave her as little presents. The same ones that ended up beneath her books on literature, psychology, and sociology, which were themselves beneath her nearly-finished Ph.D. thesis, titled Drama for Drama's Sake.

💍

In the preface to her thesis she argued that Art wasn’t Pope’s what oft was thought yet ne’er so well expressed, nor was it le mot juste, the sculpture of rhyme, Gautier’s art for art’s sake, or Baudelaire’s poetry that has no other aim than itself. “The definitions of Gautier and Baudelaire promise immense freedom, yet mostly deliver freedom from doing all sorts of other things. Instead, Art is drama for drama’s sake: its motives and its intentions are to play out our internal moods and conflicts. What Hamlet said of drama can be said of Art itself: it’s a mirror up to nature.”

“Nor is Art merely the spirit of the age, whether this be the Renaissance, the fin de siècle, or postmodernism. In my first chapter, Fin du Fin de Siècle, I’ll argue that if the times determined art, then the definition of art would constantly change, which is the same as no definition at all. Instead, art is a constant: it’s the desire to express our variegated and contradictory moods, our crazy amalgam of ideas. Sometimes it’s an attempt to find a resolution to our inner conflicts, but most of the time it’s simply a way to play out — to mimic or mirror, or whatever words one wants to use — the drama of our lives. This desire is as old as our struggle to accommodate ourselves to the world around us.”

“Even when the artist reaches to the stars, peopling them with dramas that show us who we are in mythic terms, that same artist draws these dramas down into our daily lives. On earth as it is in Heaven.”

In the middle chapters of her thesis, Martine argued that people encountered problems when there was a gap between consuming and creating Art. She illustrated this with the lives of her own mother and father. “Their suicides were the result of them living other people’s versions of Art, instead of creating their own. They failed in their Art because they failed to become artists. That is, they failed to dramatize their own inner torments in ways that worked them through, providing catharsis to alleviate the stagnation of tragedy, and providing a runway of laughter to fly over the head of absurdity. They lost themselves in the dramas and in the aesthetic theories of other people — instead of creating their own patterns that allowed their inner selves to adapt to the world around them. In brief, they failed because they didn’t follow Blake’s credo: I must create a system or be enslaved by another man’s.”

Martine hadn’t told Kenneth yet about her final chapter, Drama Queen. It brought everything into the present. In it, she argued that most of what we do is imitation, but much of what we might do is Art. Her final illustration involved a scenario in which she imagined her own fate as a writer of a thesis, slowly, inexorably zooming in on the local habitation and the name. “This thesis, Drama for Drama’s Sake, is as much conjecture as it is argument. I build all sorts of meanings into my terms, my understanding of academia, my relationships with my colleagues and with a visiting scholar, who may be a robot, for all I really know about him.”

“All I can really know, whether in lines of argument or lines of colour in a painting or photo, is that my ideas are projections of what I imagine him to be: one of those Anglo brainiacs who can’t make the connection between the brain that thinks and the heart that keeps it thinking, no matter how hard she tried to get him to look in that direction.”

The artist in her could of course help him to understand his inner self as best he could, by meeting him in a cafe and exposing the blue tints of kyanite between her breasts, but she still couldn’t force him to do the same: to tell her what was really on his mind.

Kenneth was sure that Martine could become a star, if only she would stop wasting time on comic books and afternoons with Antoine at La Maison de Verlaine. He admired her immensely, and yet she drove him crazy. Literally crazy, to the point where he clenched the tablecloth as if it were Antoine's throat. Beneath the cool English façade he displayed to the amusement of his French colleagues, Kenneth yelled at her imaginary image: Why’d it take a year to tell me you were once engaged to that pretentious twit?

💍

Next: 🎲 At the Caffè

Contents - Characters - Glossary: A-F∙G-Z - Maps - Storylines