Crisis 22

The Dangerous Years

Parallels - Years - Puppetry - James Bond - Daughter of Darkness - Spoiler Alert

⚔️

Parallels

In ⚔️ The Dangerous Years and 🌪 The Eye of the Storm I see the Ukraine War in light of the 1965 Indonesian crisis that Christopher Koch explores in his 1978 novel The Year of Living Dangerously. The two conflicts are very different in terms of culture and geography, yet both involve dictatorship, propaganda, brutality, brinksmanship, global power struggle, the clash of ideologies and cultures, the collateral damage of innocent victims, the use of massive violence against specific groups of people, and charges of colonialism, imperialism, human rights abuses, & genocide. Much of what Koch has to say about political violence, civilian trauma, imperialism, political rhetoric, idealistic struggle, etc. he says through his literary structure, which is an impressive and complex one that will provide a wide contextual space for discussions of the Ukraine crisis.

Comparing the Ukrainian crises to the Indonesian crisis might help us to understand ✫ the relation between the Cold War and the present crisis, ✫ the human cost and the collateral damage of war, ✫ the multi-faceted nature of the crisis we’re facing, ✫ the hybrid nature of Russian rhetoric, distortion, and subterfuge, and ✫ the way others have coped with catastrophic violence and suffering.

Because the Indonesian crisis occurred 60 years ago in the southern hemisphere, during the Cold War, and in a country that just achieved independence from the Dutch, it helps us make comparisons to contemporary Russian use of terms like Cold War, colonialism, imperialism, Third World, and global south. Russia’s claim in the 1960s to be fighting with the Third World against the capitalist West was harder to counter in the 1960s, what with the Vietnam War destroying much of the good name America garnered after WW II and Korea. During the Cold War the Russians claimed they were fighting for Vietnamese (or Cuban or Nicaraguan) freedom from Western imperialism, and today they continue to make a similar claim in regard to “the global south.” The idealism of their Cold War claim was always deflated by their suppression of Eastern Europe, and it lost all its air with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The rhetoric is emptier now than ever, now that they are themselves the imperialists. One might even call them genocidal colonialists — for two reasons: 1. they’re the only European power that instead of backing away from colonialism has attempted to reinstate it as a legitimate enterprise; 2. they deny Ukrainian identity and seem intent of destroying it, and they are bombing civilians and vital civilian infrastructure (dams, apartments, power stations, etc.).

The fact that many people debate if we’re in a New Cold War suggests at least two things: 1. the old Cold War is deeply connected to the situation today, and 2. while we can see what the Cold War was, it’s still debatable to what degree the present situation is a repetition of the past.

Looking at the present Ukraine crisis through the lens of a unified novelistic treatment of the past Indonesian crisis might also give us a certain critical distance. It might help us to see details as well as larger sweeps of political and cultural history — something that’s very hard to do with an ongoing crisis that is, for Westerners, very close to home. Seeing a past situation with some degree of context and clarity (even if this means clarity about things we don’t know), may make us more likely to see similar or different patterns in the present. In addition, using a novel might might help us to think not just in terms of politics and history, but also in terms of human meaning (as in philosophy and religion) and personal experience (as in psychology and social relations).

⚔️

Years

The title of this page comes from The Year of Living Dangerously, a phrase used by President Sukarno to describe the chaotic state of Indonesian politics in 1965, right before Sukarno was overthrown by the right-wing General Suharto.

The Danger of Titles

I initially called this page The Years of Living Dangerously, simply pluralizing the film’s singular Year. Then I saw this had already been used in a climate change series. So I thought, Dangerous Years, then I saw the 1947 film starring Marilyn Monroe. So I thought, The Dangerous Years, then I saw the 1978 novel by John Harris. The novel deals with Western powers in Russia at the end of WWI. So I thought, good enough.

The Australian writer Christopher Koch (1932-2015) uses Sukarno’s phrase as the title of his 1978 novel, which was made into a powerful film in 1982, starring Mel Gibson, Sigourney Weaver, Helen Hunt, and Bembol Roco. The film is directed by Peter Weir, and does an excellent job of getting into the depths of a complex work of literature.

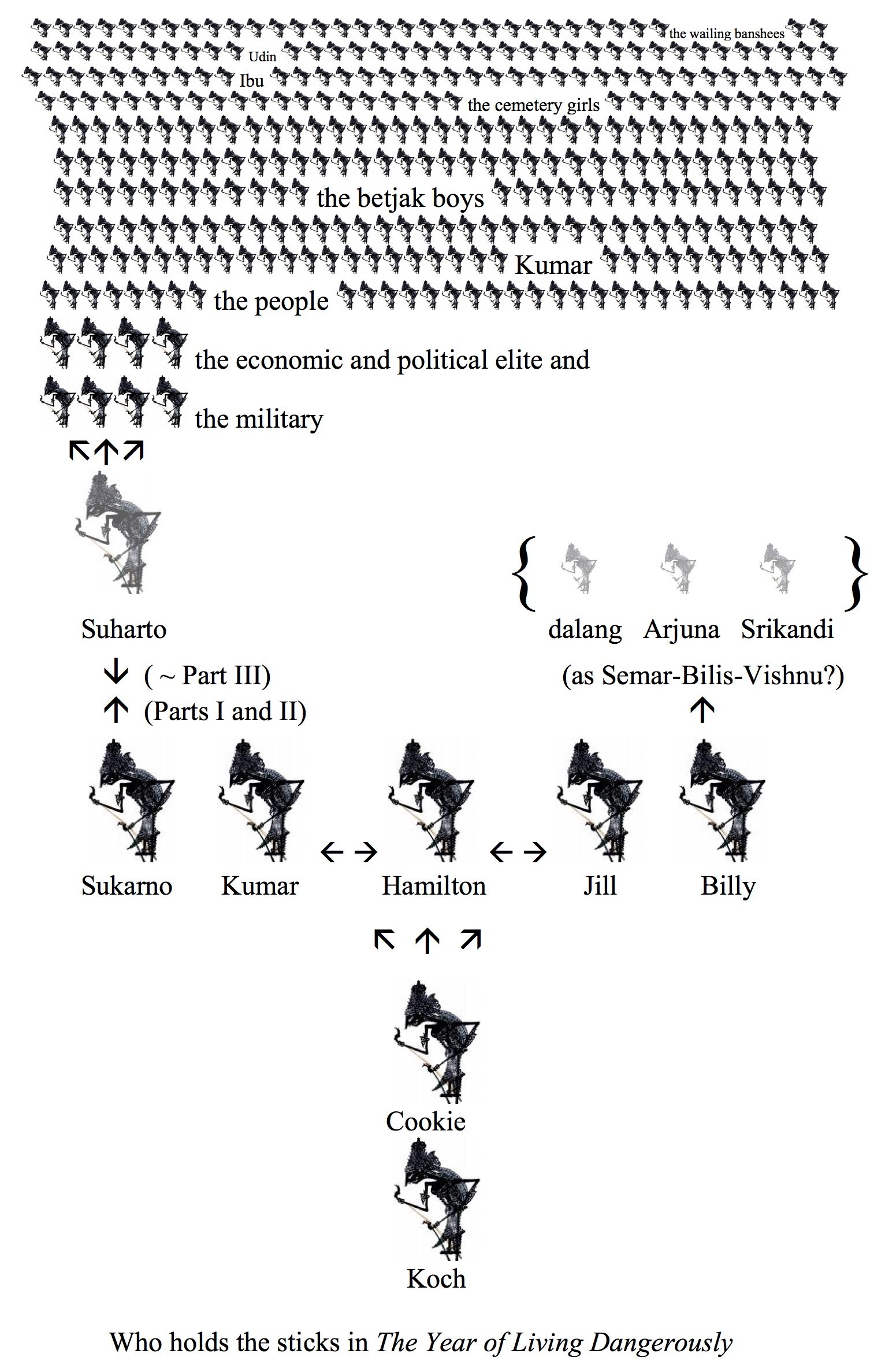

As I illustrate in the chart below, The Year of Living Dangerously is an intricately structured novel. Koch attaches powerful symbolism to those who hold power as well as those who don’t — for example, the desperate prostitutes at the cemetery, the impoverished pedicab drivers or ‘betjak boys,’ a woman named Ibu who is forced by poverty into prostitution, her son Udin who is poisoned by the canal water they drink — all of which leads to the pathos-laden spectacle of Udin’s funeral caravan, winding through the streets of Jakarta, led by the betjak drivers. Koch deals with elite politics, espionage, sabotage, etc., yet he also deals with ordinary people whose lives are ripped apart by the larger forces of economics and politics.

Something similar happens in the Ukraine crisis: global powers struggle for economic and military control, the Kremlin uses this global situation as an excuse to invade Ukraine, and those without power (both in Russia and Ukraine) end up fighting the war, having their homes destroyed, losing limbs, losing their lives, lising their brothers and fathers, their illusions, their hope…

⚔️

Stick-Puppetry

Koch constructs a subtle and elaborate narrative structure for his novel using the Wayang stick-puppet theatre. This theatre contains a mix of Hindu and indigenous mythology and narrative. It’s used in Indonesia as a form of entertainment and insight on the everyday level, and as a form of commentary on the political level.

As I emphasize in my graph above (with its fractal puppets), Koch uses Wayang puppetry to show who attempts to control or ‘hold the sticks’ of both the political and the literary narratives in the novel. Ultimately of course the novel is controlled by Koch, yet he sets up a narrator (Cookie) and this narrator sees events largely through the eyes of the protagonist, the Australian journalist Guy Hamilton. Cookie also attempts to see events through the eyes of Hamilton’s cameraman Billy, although Billy is an erratic and in some ways delusional guide to events. Cookie gets hold of Billy’s files after the cameraman dies, and he quotes them and comments on them throughout his account of events, which constitutes the novel. Cookie’s comments on the sources of his account and on the ways in which meaning slips along the sticks makes the novel a realistic metanarrative.

We see the national political narrative first in Sukarno, who believes himself to be the puppet-master (or dalang) of the nation. Yet Sukarno’s power slips throughout the novel, and eventually it’s subtly usurped by Suharto. (Sukarno effectively ceded power to Suharto in March 1966, was put under house arrest in March 1967, and died in June 1970). Cookie comments that “no one can pretend any more to be the dalang when he has become merely one of the puppets.” (Sort of like Lukashenko? To what degree is Xi holding Putin’s sticks?).

While Billy has a fairly good grasp on what’s happening in Indonesia, Hamilton fails to understand how power works there, even going so far as to confront the army guards at the presidential palace. In trying to get at the truth, he’s bashed in the face with a rifle. His blinded, bandaged eye symbolizes his inability to see, yet it also hints at a Western inability to understand other nations and cultures.

Cookie writes his account from his cousin’s hilltop farm in Australia, which provides him a spatial and psychological distance that’s necessary in order to get traumatic and complex events into perspective. Yet Cookie also admits that he doesn’t completely understand his own protagonist. Hamilton also tries to control — or ‘hold the sticks’ — of his lover Jill, who gets secret information from the British Embassy yet implores him not to act on this information, and his assistant Kumar, who appears to be powerless but has deep links to the Russians and the Communist Party.

Hamilton initially controls but finally ‘fumbles the sticks’ of his cameraman, who is in many ways the moral centre of the novel. Billy has high political connections yet he prefers to focus his camera lens on the suffering of the poor, who are all but forgotten. Forgotten, except in his secret files, where the people in his world are represented by the characters of the Wayang: Billy sees himself as the dwarf Semar, Hamilton is Arjuna (the prince in the Bhagavad-Gita), Jill is the princess Srikandi, etc. Billy’s optimism is seen here in an early scene where he explains to Hamilton the importance of the Wayang:

Billy hopes to use his dalang powers to control Hamilton, Jill, and even Sukarno, but the forces outside him have wills of their own: Hamilton betrays Jill’s confidence for the sake of a major journalism story, Sukarno turns his back on the betjak boys, the slum child Udin dies from infected water, etc.

At the end of the novel, we’re left with several powerful images: Hamilton leaving a small-town performance of the Wayang in the wake of the Russian spy Vera; Hamilton listening uncomprehendingly to the wailing of the transvestite ‘banshees’ from his air-conditioned room on the seventh floor of the Hotel Indonesia; Billy moving about below the Hotel in a betjak, documenting with his camera the fate of the banshees, the cemetery girls, and the betjak boys.

The film version also leaves us with a very powerful scene: Billy, distraught by the poverty of the country, the death of Udin, and the disappearance of Ibu, listens to an aria and bangs on the keys of his typewriter, “What then must we do?”

⚔️

James Bond is Alive and Well

Two important aspects of the novel that the film leaves out are the use of two Hindu goddesses (Kali and Durga, who are also figures in the Wayang) and the sinister role played by the seductive yet brutal Russian agent, ironically named Vera or Truth.

The Hindu goddesses serve at least two purposes in the novel: 1. they balance, and perhaps wreak vengeance on, the self-promoted image of Sukarno as a decadent Shiva (the ithyphallic god of destruction & creation), and 2. they incarnate the horror of the slaughter of the Communists, Chinese, and assorted leftists, a horror which follows Suharto’s takeover (the 1965-6 massacres take .5 to 1 million lives). At the end of the novel the readers are left with grim images of genocide and apocalypse — as in this depiction of Kali, who iconically wears a necklace of skulls:

… as the year ends, it will be said that half a million have died, perhaps more. Who will ever know? In circles of lanterns in the paddy fields at night, the cane-knives will chop and chop at figures tied to trees; and trucks will carry loads of human heads, all pleasing to the dancer at the cemetery.

Two main aspects that Peter Weir leaves out of his film — the Hindu goddesses and Vera — come together in the novel, when Billy sees Vera as Durga and Kali (I should note that Hindu goddesses are often merged into one mother goddess):

Every line of that body (corpse-white, as those of the red-haired always are) betrays a daughter of the Drinker of Blood.

Durga! Uma! Kali! You of many names: Time, and Sleep, and the Night of Doomsday! You who offer bliss, and dark disorder!

Even the narrator Cookie comments: “Billy Kwan was right: Sir Guy had been invaded, since his trip to Tugu, by ‘Durga’s darkness’, by a mysterious lust.”

⚔️

Daughter of Darkness

The role of Russia in Koch’s Year isn’t as easy to see, nor as mythically-laden as the figures of Kali, Durga, or Dewi Shri (who incarnates the spirit of the countryside, far from the Jakarta elite and the Hotel Indonesia). Russia is at once very distant (even murkier than China) and very close — as close as Vera, who pops up into Hamilton’s life like an irresistible Jezebel or Delilah.

Two-thirds of the way into the novel, Hamilton drives up from the congestion of Jakarta to the wide-open hills where he sees a vision of Dewi Shri, watches a village performance of the Wayang, and succumbs to Vera’s charms. On the outskirts of Bandung, Hamilton happens upon a traditional performance of the Wayang. A friendly villager starts to explain to him what the stick-figures mean, what advice Krishna has for the prince Arjuna on the battlefield — when suddenly Hamilton is pulled away from the play of shadow and light by Vera, who is beautiful and mysterious in an opposite sort of way”: while the Wayang leads to insight, light, and vision, Vera leads to confusion, darkness, and blindness.

Vera takes Hamilton to an old Dutch hotel and then drugs him in the hope of getting information about a Chinese arms shipment for the Indonesian Communists. The narrator makes the following comment:

Few of us consciously make contact with that sub-world of espionage which is the myth kingdom of our century. Intelligence agents from a foreign power are rather like hobgoblins in most people's minds: not consciously seen, they are irrationally thought not to exist outside the fables of the entertainment industry. I've known fellow-journalists with this attitude — even though some of their colleagues, unknown to them, were agents themselves, using the job as a cover. (Do you believe in fairies?)

Vera was a shadow, and would remain one. With the bogy mask of the Soviet Union looming behind her, she could never become a person for him.

While Billy becomes increasingly extreme and puritanical in the novel, he’s also the one character who cares deeply about what’s happening to the Indonesian people. Perhaps he cares too deeply. He’s also the one character who’s convinced that Vera’s meddling isn’t some cinematic game, some mere Bond entertainment. Rather, he believes that it’s destructive on the political level (of global Soviet-style communism) and on the personal level, where it severs the bond between Hamilton and Jill. Billy addresses Hamilton in his secret files:

You are inconstant, when I had thought that constancy was your chief virtue. Hamilton, you betray our darling through the same sad lechery which keeps a man like Curtis [who goes to the cemetery prostitutes] tied to the wheel!

Dear God, it's a matter for weeping.

But the spy is spied on. I am beginning a file on your KGB lady, here where all my images are made and stored! What scorn in that white Tartar face, as she looks at you! Can't you see? Fool, you fool, from a continent where ignorance is virtue, where bogies exist only in old, wicked countries overseas — or in your perverted Fleming thrillers! Can't you see?

⚔️

Spoiler Alert

Toward the end of both the book and film, a desperate Billy goes to The Hotel Indonesia, where Sukarno is scheduled to pass by in his limousine. The great god-king will give a brief, self-congratulatory wave toward what in the novel is described as the brightly-lit theatre arcade of the hotel’s entrance. Billy drapes a sign out of a lower-story window: SUKARNO FEED YOUR PEOPLE.

He then falls, or more likely is thrown, onto the pavement below.

The defenestration of protesters, political opponents, cameramen, and journalists. It happens in other places too.

The brutal death of Billy and the apocalyptic motifs at the end of the novel are appropriate in terms of the grim themes Koch treats throughout the novel: the manipulations and abuses of dictatorship, the collateral damage of a global power struggle, espionage and sabotage, the struggle between political systems, violence in the name of idealism. All of these climax in the mass murder of innocent civilians and the horror of slaughter and apocalypse.

Unfortunately, many of the themes in The Year of Living Dangerously are playing themselves out once again on the international stage. This time, however, Russia isn’t playing a secretive, espionage role, but is at the very centre of it all.

While in Koch’s novel the Russians play a covert role — they spy and scheme instead of drop 3000 kg bombs — The Year of Living Dangerously reminds us that their spying and subterfuge isn’t a thing of the past. Rather, it’s part of a less obvious yet wider, deeper danger: the hybrid war war they’re waging from Minsk to São Paulo, and from Moldova to Pyongyang.

⚔️

Next: 🌪 The Eye of the Storm