Gospel & Universe 🍎 The Apple Merchant of Babylon

Moses & the Apple Merchants of Babylon

Free Trade

Moe learned to like doing business in the shop out front. It gave him a chance to meet all sorts of people and swap stories about the world around them. The only thing that bothered him was that there were very few ethical guidelines, and whenever they agreed on an ethical guideline no one followed it.

Moe figured it was the fault of the Indian fruit dealer Shesha. Ever since he brought in Kashmiri apples, people stopped buying the local fruit. They were frustratingly delicious. They were even better, Moe feared, than the ones from his family orchard on the outskirts of town. Moe tried to rally his family against the Indian, but all his family cared about was profit. They just wanted to make deals. And Shesha was the man for that.

Moe felt the same lack of interest when he talked to them about Yahweh. He repeated the old mantra about their God being better than all the others. It was a God who was above all the other gods, and who would unite everyone once and for all. But they just nodded their heads and said, OK, whatever. The only one who'd listen to him was Abe, and that was because Moe was his favourite nephew. With everyone else, it was profit over prophecy. They were deaf as doorknobs to his protectionist arguments and to the roar of his omnipotent God.

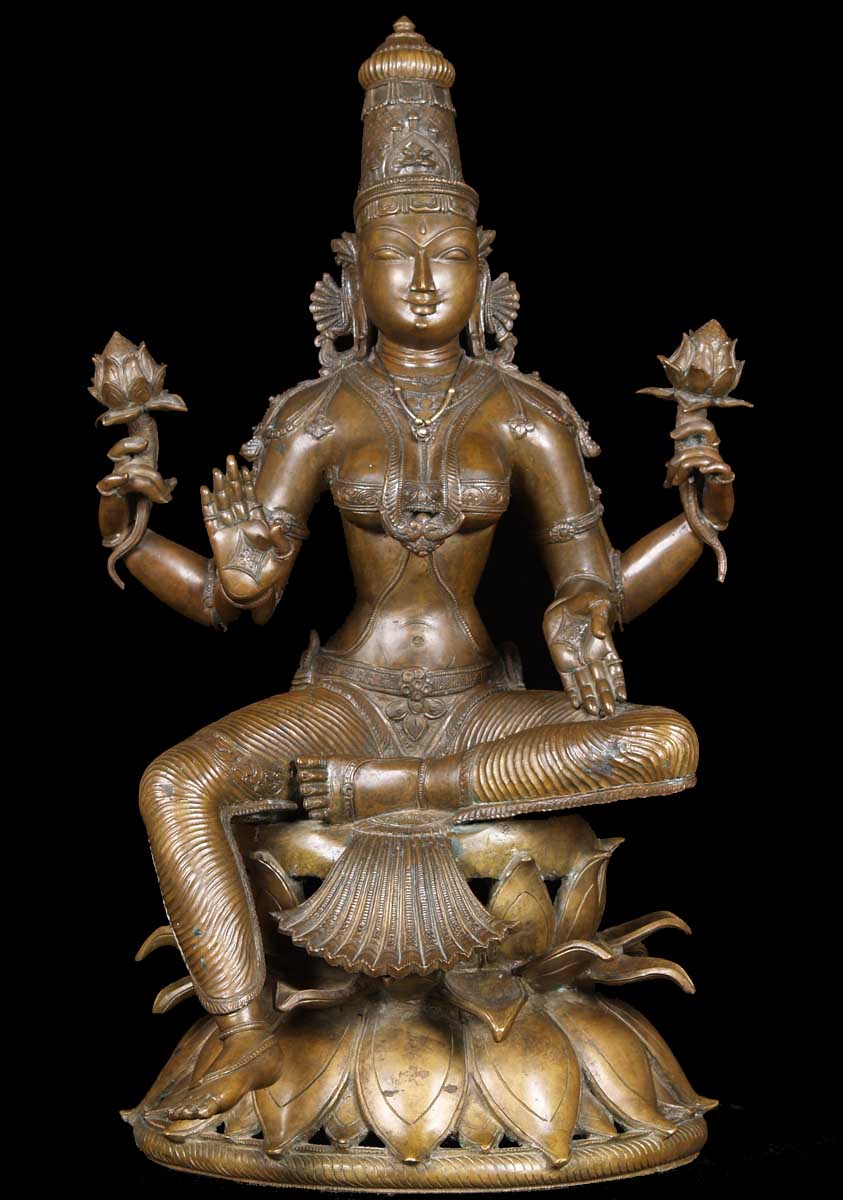

To make matters worse, everything Indian was the rage. Everyone in the market admired Shesha’s bas-relief of the goddess of Fortune. She had large breasts and spun something that looked like an apple on her finger, while happy elephants munched exotic fruit.

Moe's cousin Qayin traded his bronze six-pointed star, the symbol of their God, for a fancy iron image of the goddess of Fortune. Iron was all the rage. No one valued the old traditions anymore. It didn't help that the goddess had big round breasts, and that his God didn’t have any breasts at all. Yahweh didn’t even have a handsome face, or strong smooth hands. In fact, He had no body parts at all. Even worse, the goddess wasn't afraid to act like a flood-plain girl when some of the other gods came around. She multiplied shekels like children.

🍎

Olive Branches & Holy Mountains

Beneath his shop sign, Moe put up a small statue of a god meditating on the peak of a mountain. He made this compromise with the gods of India in the hope that the god’s asceticism, his deep breathing among icy peaks, would cool the avarice that possessed his fellow merchants. It should be noted however that Moe placed Yahweh’s six-pointed star above the god, just to make clear who was above who.

Moe made a further ecumenical gesture by writing some complimentary things about the Indian gods in his weekly journal of culture and religion, The Holy Mountain. He surprised his uncle Abe when he claimed that there were similarities between the older, more elegant Babylonian religion and the ingénue cults from India. Moe reminded his learned readers that according to Sumerian and Akkadian records, humanity descended from the mountain on which Utnapishtim’s boat landed after the Great Flood. He noted that Utnapishtim was warned to build his boat by Ea, the god of sweet waters. Likewise, according to Indian accounts, humanity descended from Manu, after Vishnu warned him of the coming Flood. Logically, there couldn't be two first humanities, so Moe concluded that the mountain must be the same mountain.

In a truly exceptional gesture of goodwill, Moe suggested that the original Holy Mountain may have in fact been Mount Meru, which the Indus people said was the fixed centre of the cosmos. Around it revolved the sun and all the planets. Moe took this opportunity to chisel a series of interlocking hexagons into the tablets of the journal. He knew that Babylonians loved sixes, and he wanted to make them feel part of his blossoming ecumenical community. He coloured his hexagons red, yellow, and blue to signify the earth, the sun, and the water that descended from the Holy Mountain and made everything possible. Swept away by his own enthusiasm, he claimed that from these primordial colours came the colourful multiplicity of the world.

Beneath his colourful triangle he chiselled, in his most elegant cursive (well, at least as elegant as his stylus and hammer would allow) an encouragement to all who sought Higher Truth: Whosoever seeketh Divine Wisdom, let him climb the Holy Mountain!

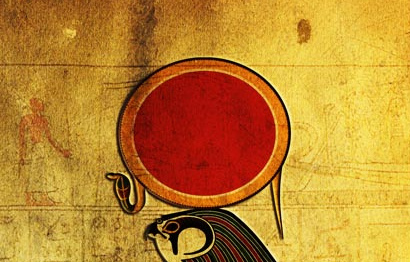

Intoxicated by the spirit of ecumenicalism, Moe reached out even further, to the land he always imagined as his own: Egypt. He knew that Akhenaten had tried to make the sun god the only god. Wasn't this what he wanted for his family's own tribe: a One True God? Just because Akhenaten's attempt failed didn’t mean we should give up on the idea! Wasn't Amun-Ra the creator of life, and hadn't He created man from His tears? Didn't He circle the world every day, and also make a nightly journey across the land of the Dead?

Fired by the glory of this mythic archetype, Moe chiselled a perfect circle at the top of a new tablet. He liked this switch from the triangle metaphor to the circle metaphor. Wasn't the One True God beyond geometry? Beneath the image of the sun-god, he made an outline of two columns, one in Babylonian cuneiform and the other in the simple new 'Aleph-Bet' script used by the Phoenician traders. In the two columns he wrote the following poem:

Ra

You who are always beyond our reach,

You who are sixty times sixty times sixty cubits from the earth,

Yet still we cannot look you in the eye.

You who are the origin of all life,

Who created man from the compassion of your tears.

Why look further for an image of God

Than this perfect circle of blinding light

Lighting the world in Its spinning flight?

Moe hoped that one day this poem would be read by children all over the civilized world. Perhaps his dual-script version would even help them to read the simpler Aleph-bet script that was now so snobbishly seen as only fit for workers and merchants. Wasn't he a merchant? Maybe if the other merchants could see that there was only one God, and that He was unattainable and that it was impossible to even look at Him (like the Sun) then they would stop all their religious quarrelling and favouritism, and get back to business.

Yet instead of prompting the merchants to think of higher things and of the common economic good, his discussion of Amun-Ra and the Holy Mountain only encouraged the shop sellers to import more pagan statues.

With the extra cash, the Persian middlemen bought more apple carts. The markets were soon glistening with the shiny russet spheres of Kashmir and Susa!

This was the last time Moe would ever compromise with the evil deities of a foreign land.

🍎

Next: Eastern Gods