The Double Refuge 🦋 Butterflies Landing

A Positive-Sum Philosophy

Superlatives - Plusses & Zeros - Tolerance

🦋

Superlatives

If you say My country is great, no one's likely to say that you're wrong. People's opinions differ, and almost everything in the realm of preference is relative. Except of course that context plays a role here: if you're in the West in 2024 and you say Russia is great, others are likely to set you straight, especially if they’re Ukrainian. Yet when someone says My country is the greatest, there'll be an instant debate, often heated. By saying it's the greatest you're saying something like it has the best people, the best culture, the best approach to life, the best nature, the best cities, etc. The generality that let you get away with My country is great no longer applies; people will quickly argue that other countries may be just as great or even greater. And once you get into specifics, the debate never ends.

Likewise with religion. Apart from the New Atheists (who reject all religions), few would find it offensive if you say Christianity is great, Hinduism is great, or Islam is great. Of course, the context is important here. If you're shouting this while burning a library in Alexandria, taking apart a mosque in Ayodhya, or driving through a crowd shouting Allahu Akbar, people will most forcefully disagree. But if you calmly assert My religion is great, very few people are likely to get upset.

But if you say My religion is the greatest, the same problem occurs as when you assert My country is the greatest. The same problem, yet worse in some ways. This is because the view of a country involves pride and culture; it isn't a philosophical or universal judgment about truth.

A statement about the best country is obviously relative, and can be qualified and debated by comparing people's opinions on language, economics, nature, art, etc. A definitive statement about the best religion on the other hand is almost always a judgment about universal truth. It generally signifies most true and in some cases it signifies the only truth. And no reasonable people, whether they have another version of the truth, or whether they reject the notion that there's only one truth, are likely to take such a statement sitting down.

🦋

Plusses & Zeros

In The Double Refuge I look at religious systems from a positive-sum perspective, which means I see differences as diversity rather than as competition:

Christianity+1 + Hinduism+1 = 2 great traditions

religion+1 + science+1 = 2 great takes on life

The result is a sum of two, rather than the sum of zero we get when we see differences as competitors that cancel each other out:

Christianity+1 + Hinduism-1 = 0

Hinduism+1 + Christianity-1 = 0

religion+1 + science-1 = 0

science+1 + religion-1 = 0

I try not to exaggerate the positive or negative things I find in religion & science, although it’s pretty hard not to see the damage. Christianity surrounds and frustrates me because of ✖️ its exclusivity (its claims about the one Truth, the Elect, the Chosen People, etc.), ✖️its cooperation with authoritarians (like Hitler, Putin, and Trump), and ✖️its antagonism to science and liberalism. Yet Christianity also amazes and inspires me, especially when I look at ✰ its emphasis on forgiveness and redemption, ✰ its close ties to humanism, secularism and liberalism (paradoxically, it has also been a stumbling block to these…) ✰ its service to the poor, disabled, sick, and old, ✰ its liberation theology, ✰ its writers like Dante and Milton, ✰ its ecumenicals and universalists like Thomas Merton, Matthew Fox, and Richard Rohr, and ✰ its magnificent art — which intoxicates me, and takes me back in time to the southern lands of virgin births, ornate columns, and well-dressed angels…

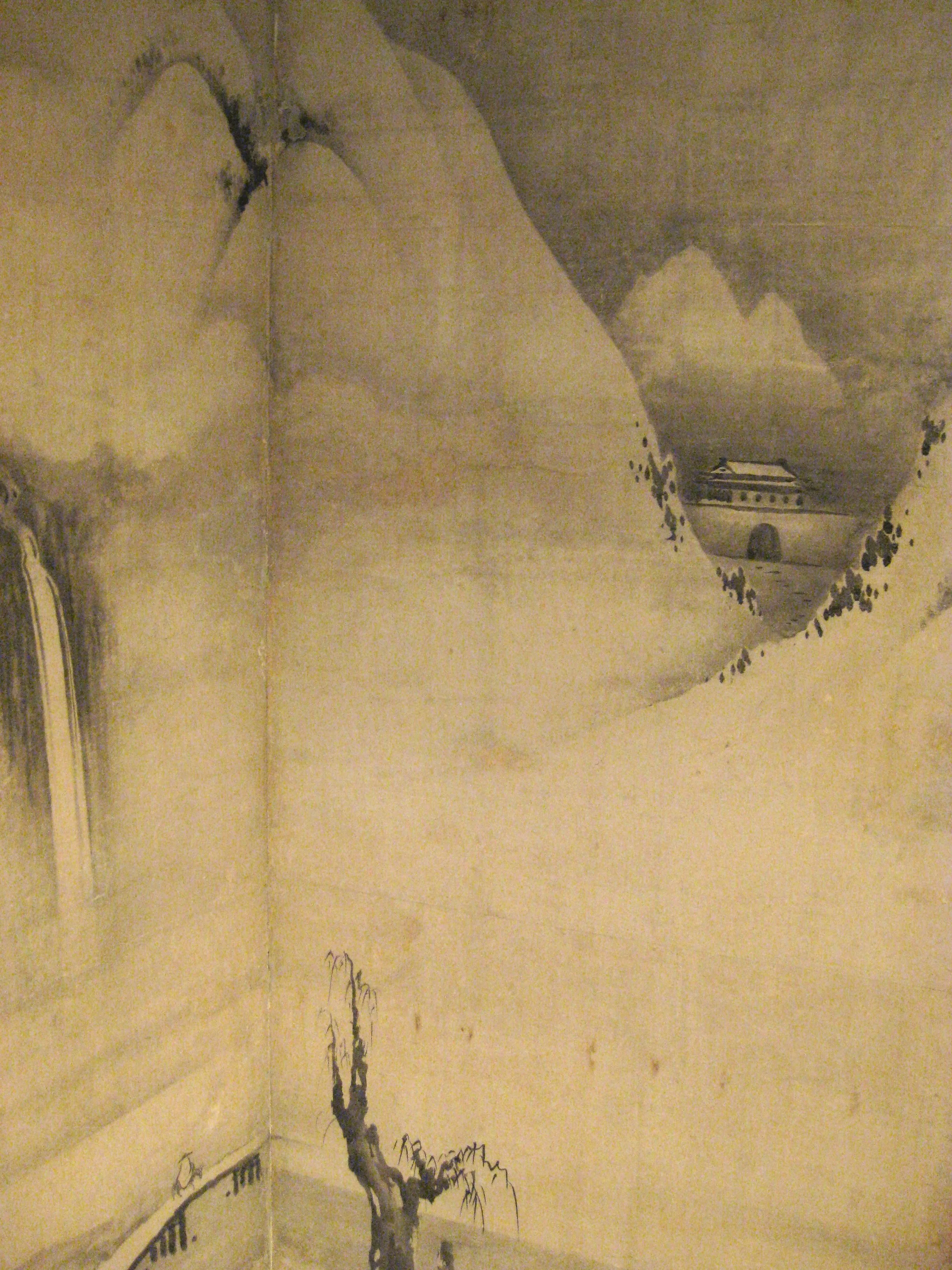

Just as I criticize & praise Christianity, so I criticize & praise other religions. For instance, I applaud the poetry of the Vedas and the diversity of Hindu myth & philosophy, yet I also critique caste, hierarchies of enlightenment, and claims about the superiority of Bhakti devotion or non-dual Vedanta. I also look at religions such as Buddhism, which borrow from Hinduism the notions of dharma, karma, samsara, & nirvana (duty, action, rebirth, & liberation). While I doubt these notions, I find in Eastern religion & philosophy a great deal to ponder, from the quasi-existential views of some Buddhists to the flowing openness of Daoists, to visions in art where the human being is but a detail in the greater picture:

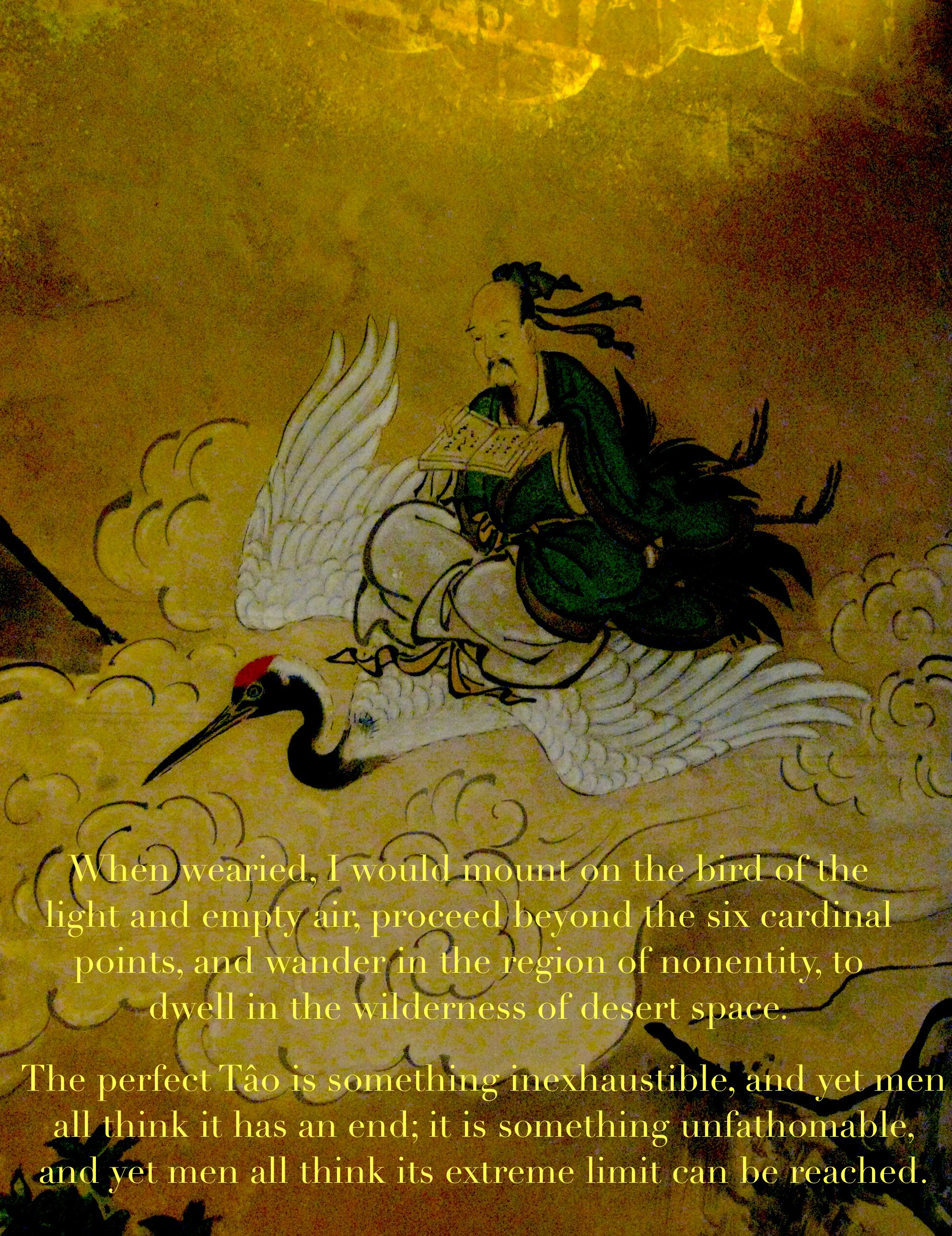

I also have a bias toward non-dual Christianity (especially the cosmic or universal Christ of Fox and Rohr), non-dual Hinduism (especially Advaita Vedanta), and Daoism. The latter is perhaps the least doctrinaire of major world religions. This is especially true if one focuses on the Classical writers Laozi & Zhuangzi, who don’t write about longevity, alchemy, ghosts, or metaphysical powers. Instead, they stress infinity, ineffability, and exploration. They argue that we don’t know the meaning of life, and that we shouldn’t go on about it even if we did. Zhuangzi is particularly poetic when he highlights the notions of a destination that has no location and a journey that has no end:

When it comes to Islam, I try hard to strike a balance, although it would be odd not to notice that Islam is today’s most abused and divided religion. In my chapter 🇮🇳 The Fiction of Doubt I try to balance the positive and the negative, applauding Rushdie’s use of Islamic mystical motifs, yet also highlighting his critique of extremism and militarism. Often the criticism & praise go hand in hand, as when he uses Hindu and Muslim notions of control & freedom in his accounts of communalism and the parliamentary Emergency of 1975-7. In Midnight’s Children he draws moving portraits of the pregnant Amina, who stands her ground against a gang of xenophobic, homicidal Muslim zealots. In Shame the doomed Muslim cinema-owner plays a Hindu-Muslim double-bill, which Rushdie calls the double-bill of his destruction. Even in The Satanic Verses, Rushdie’s most explosive work, the notion that the novel only attacks Islam is odd, given it’s narrative postcolonial dream-framework and it’s subtle yet very powerful homage to Sufi and Christian ideals of peace.

In general I take a positive-sum view of religions. The only things I treat negatively are exclusion, dogmatism, and the notion that there is only one true religion or only one way to understand religion. While I focus largely on this problem in Christianity, Islam has more than its share of problems in this regard.

🦋

Tolerance

Some might argue that being intolerant of intolerance is just as illogical as doubting doubt. Yet I’d counter-argue that both are paradoxes, not contradictions. Furthermore, I’d argue that they’re related: the freedom to debate and explore the relation between doubt & belief is put in jeopardy by religious intolerance (as in Iran) and by atheist intolerance (as in Soviet Russia). In a wider sense, all philosophical and political debate is put in jeopardy by those who would mix religion and government in order to silence the types of questioning exercised by agnostics and free-thinkers. The converse is also true: freedom is likewise threatened by those who insist, as many communist governments have done, that religion is an opium that must be banned.

It’s difficult when intolerant or dogmatic religious parties are voted into power. We can see this, with different results, in Iran, Algeria, and Egypt. We can also foresee it in the MAGA crowd using a free election to take power, after which they proceed to dismantle the constitution, the freedom of the press, and liberal democracy in general.

And it’s often difficult to predict whether or not an intolerant power will allow itself to be voted out of power. In the case of the U.S. it seems that democracy will win out (at least for now…), yet in the case of Iran it appears impossible, given the power of the revolutionary guards, the mullahs, and the supreme leader. Likewise, in Russia the Kremlin short-circuits real change by muzzling critical press (like Novoya Gazeta) and even killing press members and opposition leaders (like Alexei Navalny). What to do in a country where dissent is disorder, and order is what the leader says it is?

In 🇮🇳 The Fiction of Doubt I explore how Rushdie deals with these types of issues, especially in the context of Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan. In all cases he creates a fairly clear divide between authoritarianism and the freedom to follow — or not follow — a religious agenda. His thinking in this regard is very much in line with basic democratic and liberal values.

I’ll argue throughout The Double Refuge — as well as on the next page, Freedom of Thought — that these freedoms are fundamental to the full operation of belief, doubt and open enquiry.

🦋

Next: 🦋 Freedom of Thought