The Double Refuge 🎲 Almost Existential

Starbucking

Moksha Latte - At Starbucks

🎲

Moksha Latte

I've drifted from belief in particular things (Christianity, Nothing At All, Taoism, Hinduism, Agnosticism) to belief in the religion of Infinite Space, to the annihilation of self, and to sitting in Starbucks buzzed out of my mind on matcha lattes.

I think about Walt Whitman's phrase, to be both in and out of the game, while Nina Zilli's Una Breve Vacanza dances between my headphones: Meglio così / It's better like this / Camminare sospesa / To walk suspended / A passo lento / Slowly / Tra finito e infinito / Between the finite and the infinite / Nel breve spazio / In the short space / Che contiene un minuto / That a minute contains.

I think about the hundreds of billions of galaxies and the time it takes to get there, and yet I can’t even imagine the mind of a Deity that could take this dust from there to here.

This moment of expansion is mine, but the cause isn’t, because I know too well that Prufrock’s hair is getting thin, and that there are too many prophets in the blogosphere for me to become some beaming star, so I swallow this strange day, this sequence of moments in my local Starbucks writing in this Notebook of Air the strangeness of the last 24 hours: how the fear and coercion just drifted away , all of those things they told me in Sunday school about Hell and Judgment drifted away; how the gulf between belief and hope was replaced by a sky-bridge connected on both sides to solid earth.

All that was left was space — and jagged cliffs of precipitous rock

Let those who believe in le bon Dieu continue to do so. I hope they’re right. Hope's a fine thing indeed when it's no stranger to doubt. The latte's almost finished, and the vision's fled. All that's left of it are words.

🎲

At Starbucks

The agnostic applauds transformation, and desires to remain open (dare I say, faithful?) to the reality of whatever it is they’re experiencing. They try to avoid focusing on one part of the process and making it into a fixed standard or icon.

To some fundamentalists iconoclasm (from destroying icons in Greek) means smashing other people’s icons. Yet iconoclasm can also be a personal, mystical, secular, democratic method of dismantling ideas that are unnecessarily limiting. Everyone uses this method to question rules and dogmas that don’t correspond to their understanding or experience. Mystics use it to open up avenues of interpretation, to escape fixed readings of sacred texts and traditions. Secularists use it so that religious laws (which some want to follow) don’t trump practical laws (which everyone can follow). Democrats use it to maintain an open, fluid society, one in which laws and systems aren't set in stone by militarists, monarchists, corporate oligarchs, commissars, mullahs, fundamentalists, etc.

Agnostics and poets use iconoclasm like the others (to go beyond formulas, dogmas, and ideologies) yet for them it's more a basic mode of operating, a manner of seeing, thinking, and feeling. They use it to break apart the solid conception of things so that they can see new ways these things might be re-arranged. To see what else might come of them. Agnostics try to find concepts, and poets try to find expressions, that resonate with the complex, changing, combination of heart and mind that characterizes a human being.

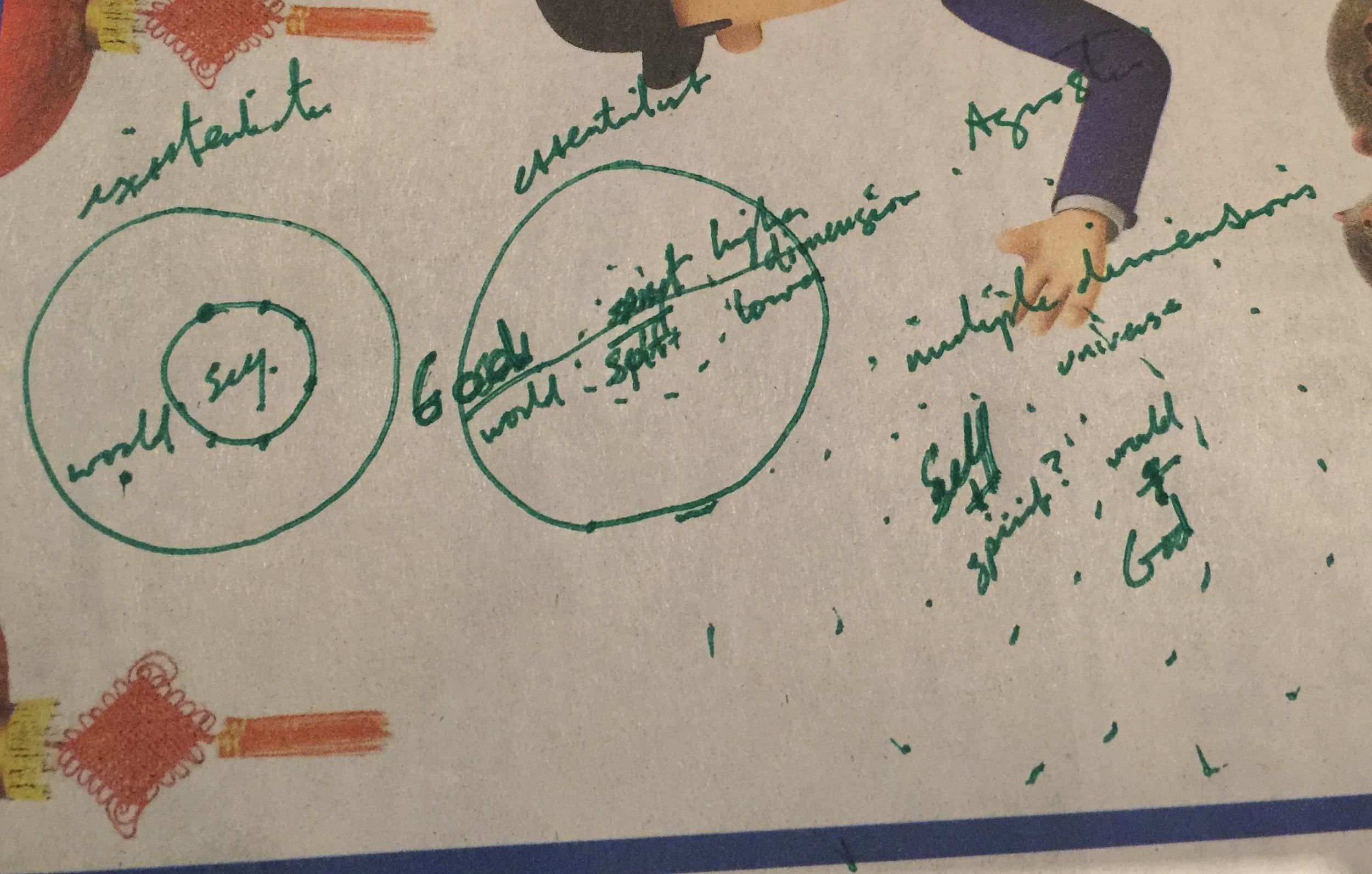

Agnostics strive to remain open to their own bodies, emotions, and thoughts, and also to remain open to the bodies, emotions, and perspectives around them. Diagrammatically, one can see the agnostic’s position as a superimposition of the positions of the existentialist and the essentialist, yet with more permeable barriers. I'll illustrate this by using a little drawing (below) I made at Starbuck's the other day on an advertisement in a free newspaper. I could put these scribblings into a neater form. I could borrow three perfect circles from the Web, and put typed words next to each of them. Yet I'd rather leave the drawing the way I first drew it, very imperfectly. I'm hoping this style of presentation will help me to convey the concept ontology precedes epistemology, because in this case the state of my being -- my ontological state: caffeinated, with my laptop on a free newspaper -- preceded the explanation of meaning (the epistemology) that I came up with.

The first circle (on the left) represents the existentialist concept that the self is separate (and in many ways alienated) from the world around it. This alienation might be seen as an extension of the empirical or skeptical idea, articulated by David Hume in his 1739 Treatise of Human Nature, that we can never know the world around us. Or if we do know it, we know it only through the lens of our own perceptions and conceptions. At the end of "Section 3: Of the Ancient Philosophy," Hume writes that there's "a very remarkable inclination in human nature, to bestow on external objects the same emotions, which it observes in itself; and to find every where those ideas, which are most present to it."

A variant of Hume's idea can be seen almost three hundred years later in Sartre's notion, most fully articulated in his 1938 novel Nausea: we can only see and hear our own nauseating reflections and that our explanations of the world are illusions: "the world of explanations and reasons isn't the world of existence." Looking at a root of a chestnut tree, Sartre's alienated protagonist realizes that descriptions of the root and its function can't really help us to grasp the existence of the root itself: "The function explains nothing: it permits us to understand in general what a root is, but not to understand this particular root" (trans. RYC).

The second circle (to the right, in the middle) represents the essentialist and his or her surrounding world. The essentialist's self is less divided in terms of the relationship between the self and the world. This self may be both physical and spiritual, yet the spiritual portion gives meaning to the physical. Moreover, both spirit and God are made of the same essence, or quintessence (which literally means fifth essence or ether) which originates in the heavenly realms and can, at least some of the time, penetrate the earth-bound elements of land, water, fire, and air.

While spirit, God, and the world may be unified in this way, the world of the Christian essentialist is also divided or bifurcated: the physical world is one thing and the spiritual world is beyond all things most of the time. In certain forms of mysticism and poetry this split disappears, and in most forms of Hinduism the two worlds consistently overlap. In the non-dual Hinduism of Vedanta, they have never been separate. The Sanskrit phrase All this is That gets succinctly at the idea that the relative world, or this, is in fact infinite, Brahman, or That. We see this in the thinking of Shankara (8th C. AD) and his Advaita Vedanta, yet also much earlier in the Chandogya Upanishad (8th-6th C. BC): All this that we see in the world is Brahman (sarvam khalv idam brahma, 3.14.1). Yet for essentialists in general, and for Christians in particular, the physical world is distinct, and distinctly inferior to, the spiritual world. What one gives to God is vastly more important than what one gives to Caesar.

My little drawing also suggests that the essentialist is rather confused. Note that the writing is sloppy: in the very middle the scribble should read spirit / self. The reason I say they're confused is that they're given an impossible task: they must — in practical terms, not just in abstract terms — reconcile God's world with our world. They must expose, impose, or juxtapose God's will, God's eternal commands and truths, in the here and now. This is no easy task. They must square absolute truth with relative truth. They must square Biblical history with human history. They must square Classical Hebrew and Christian culture with the Modern social sciences and with democratic, secular society. They must square Creation with evolution. They must square the unmoving Earth with astronomy. They must struggle with abortion, birth control, gay marriage, and an unholy host of other issues. Who wouldn't be confused? Yet despite all this, for the essentialist there remains a clear line, a clear distinction between the higher dimension of celestial essence and the lower dimensions of earthly existence. Maintaining this line gives them a divine sense of purpose, and perhaps even a great sense of inner peace -- gives them somewhere to anchor their psyches in a chaotic world. But I also imagine that the constant effort to square the single revealed Word with the many relative words must at times be exhausting.

The third circle (that of the agnostic) is far more confused. It's hard to see what's even there. There are so many dots that it's hard to see the circles clearly. The agnostic is confused in different ways than the essentialist, however. The agnostic revels in the confusion, revels in the fact that the self, the world, and the heavenly realms are a deep mystery. The agnostic doesn't confess to having figured out the meaning of life, let alone the meaning of spirit or God.

The circles of the agnostic are also slightly off the grid. The dotted trajectories don't entirely fit in with the idea of firm or clear circles; they only mirror circles insofar as they question them with dots suggesting broken or permeable lines and a preponderance of empty spaces. The world of the agnostic might be seen as a world of ellipses (dots suggesting more to come) lined up and slanting into concentric ellipses (elongated circles, like the pathways of astronomical bodies) all of which expand outward toward unknown spaces and infinite possibilities.

Near the centre of the third circle (between the body and the body politic, crowned once by God) lies a question mark. Maybe there's a soul in the body, and maybe there's a God at the centre of everything. Or maybe not. Regardless, agnostics still breathe the same air and still live in the same world as the Chinese lanterns, the salesman, and the tufts of a monkeys' hair.

Diagrammatically, theoretically, these circling dots, these permeable ellipses, seem to make sense. Yet in practicality it isn’t easy to get beyond one’s self. It’s difficult to go beyond the needs and perceptions of a body which is held up by the ephemeral yet very specific scaffolding of bones and muscle, and wrapped in the genetic contingencies of cells and neurons. We exist within the internal feedback loop of our bodies, controlled by the internal feedback mechanisms of our autonomous and non-autonomous brains. It’s a gargantuan feat to really get outside ourselves and see what others see, let alone feel what others feel. This is why the golden rule's so powerful, and so difficult to follow. How to get beyond the self-referential thoughts and feelings that separate us from whatever’s around us?

Whatever’s around us. I share Hume's skepticism about what we really know about the world around us. Yet I also think that skepticism -- like iconoclasm -- can be used as a levering device from habitual perception, so that we can move toward other modes of perception and being. Thomas Huxley's grandson Aldous would agree, as would Blake, that we need to occasionally cleanse the windows of our perception. Whether or not we'll then see the world as it is, infinite, is another matter. Maybe we'll just think about the table, about the coffee on the table, and wonder how much the plantation workers got paid.

🎲

Next: Cloud Illusions