Gospel & Universe 🧩 Introduction

The Unconvinced

The Courage of Your Non-conviction - The Convinced - The Problem With Convinced Scientific Atheists - The Problem With Theistic Existentialism - The Unconvinced

🧩

The Courage of Your Non-conviction

In doubting, agnostics aren’t completely alone: their doubt is shared, at least to some degree, by theists and atheists who also question their beliefs.

While theists, agnostics, and atheists are often seen to inhabit three separate epistemological categories (belief, doubt, and disbelief), some of them may be more alike than they seem — if, that is, we bisect these three categories with two further categories: the convinced (or the sure) and the unconvinced (or the self-doubtful).

The Convinced

The convinced group have the courage of their convictions. They believe that their truths are universal and that they apply to everyone. If others have a different understanding, they are sadly mistaken, lost, misguided, or willfully wrong. For convinced theists (often called traditionalists or fundamentalists), truth reverberates from the Wisdom of the Ages and from hallowed books like the Bible or Qu’ran. For convinced agnostics (also called hard, permanent, closed or restrictive), truth comes from the conclusion that neither religion nor science has the ability or the authority to make pronouncements about the ultimate nature of reality. For convinced atheists (the more extreme among them being positivists or New Atheists) truth comes from the ever-increasing explanations of science, which establish a solid base of understanding and meaning.

From the agnostic perspective, there are internal contradictions in two categories related to the above categories: convinced scientific atheists and convinced existential theists.

❧

The Problem with Convinced Scientific Atheists

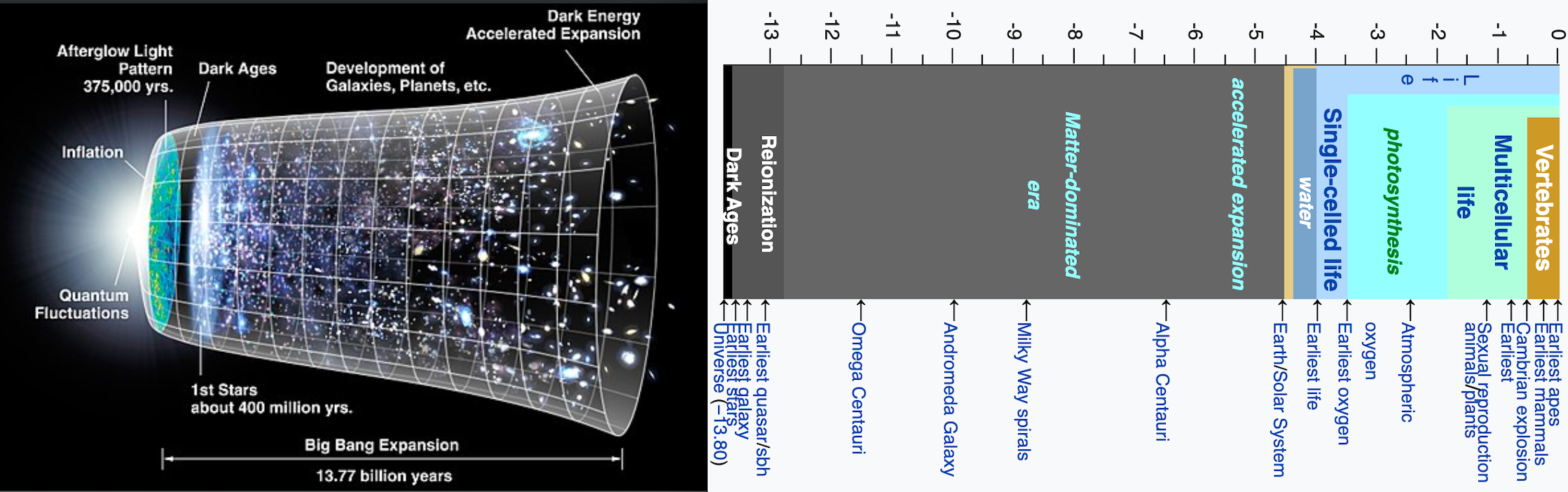

Atheists who believe strongly in science have to contend with the notion that while science can prove things, it also points to how little we know and to how small our perspective is compared to the bigger vistas of time and space.

It may at first seem odd to claim a divide between convinced atheists and scientists. Yet the convinced atheist believes science has proven there’s no God and the scientist believes science may one day prove there’s no God, but it hasn’t proven it yet. These are very different stances on a very important topic, given that the concept atheism clearly and directly responds to the concept theism. I would go so far as to say that convinced atheists can’t really claim to be scientists, at least not in the philosophic realm, for they reach conclusions that science hasn’t reached yet, or may never reach.

Oddly, it’s more consistent for theists of a mystical bent to be scientists, for in affirming their belief in theism, they’re affirming a belief, not a fact. They affirm something which has nothing to do with logic or science, something they don’t pretend to prove. I should add a crucial caveat here: my argument only works with theistic mysticism and not theology that makes specific claims about time and space — that is, claims that might be disproven using archaeology, philology, or history. By mysticism I mean the following (from the Apple dictionary):

1 belief that union with or absorption into the Deity or the absolute, or the spiritual apprehension of knowledge inaccessible to the intellect, may be attained through contemplation and self-surrender: St. Theresa's writings were part of the tradition of Christian mysticism. 2 vague or ill-defined religious or spiritual belief, especially as associated with a belief in occult forces or supernatural agencies.

The only change I’d make to this definition is in the somewhat pejorative combination of the terms vague and ill-defined. From an agnostic point of view there’s no clear definition of God or spiritual essence, so it’s odd to use the word vague. It’s also odd to use the word ill-defined, because lack of definition isn’t ill in itself (similarly, it’s odd to describe the work of scientific verification as “coldly logical”). Moreover, the vagueness and slipperiness of definition works to the theist’s advantage in regard to science: the more the language of the definition escapes the demands of verification and proof, the more likely it is to be of interest to the open-minded scientist, and of disinterest to the positivist who requires scientific proof for something to be true.

Imagine that someone says there’s a three-headed angel-fish in the Amazon River. The convinced atheist might insist there are no three-headed fishes and certainly no angels. The scientist on the other hand might say that Nature often has surprises in store, so let’s look into this claim.

The same pattern emerges if a mystic says that the universe is throbbing with an energy that lies beyond all meters: the convinced atheist might insist that nothing lies beyond all meters, while the scientist might be doubly intrigued — at first by the claim of the energy itself and secondly by the thought of making a meter sensitive enough to measure the hitherto unmeasurable.

Mystics who debate epistemology talk about an airy nothingness which yet has an essence. Who can prove them wrong? Convinced atheist scientists who debate theology on the other hand talk in a redundant circle, denying the existential existence of something that theists define as having no palpable existence here in our existential world of calculus and meters. In this sense, philosophically-minded scientists might more logically tend toward agnosticism and theism.

I say philosophically-minded here, because many scientists don’t focus on the philosophical side of science. Many come — too quickly — to the positivist conclusion that if they can’t verify something it therefore isn’t true. They assume that many of the great scientists believed in God because they had a blind spot or because this belief was a relic of their time period. Yet there never was, and still isn’t, a conflict between science and abstract theology and mysticism. Indeed, one might say that the rational scientist and the mystic meet at the point of infinity and in the subsequent annihilation of the finite self. We are tiny dots in an immensity, whether it’s the notion of God or exoparsecs that gets us to that understanding.

I previously wrote that it’s impossible to get at any fixed or complete gospel about the nature of reality or universe. Yet maybe the infinity imagined by scientists and mystics constitutes such a gospel. Maybe.

❧

The Problem with Theistic Existentialism

In looking at theology from an agnostic perspective, it’s crucial to distinguish between 1. theology which makes abstract and mystical claims, and 2. theology which makes specific claims about astronomy, physics, history, etc. While abstract and mystical claims can’t be proven wrong, specific historical claims can be proven to be both wrong and derivative: the world doesn’t stand still in space, water can’t be turned into wine without grapes and a wine-press, and the Hebrews didn’t come up with the notions of an angry god, a flood, an ark, or a new covenant (the Mesopotamians came up with these notions).

Historically-speaking, specific theological belief became more and more difficult in the 19th and 20th centuries: astronomy, geology, evolutionary theory, Mesopotamian philology, and genetics came together to provide a clear alternative explanation about how how we came to be who we are. It became more and more necessary for believers of a rational or scientific bent to take a leap of faith, passing over the incongruities and contradictions of specific religious claims to land on the side of belief. Some even used the term Christian existentialism to describe people who believe in the existence of science and logic yet also believe in the mysteries and miracles of Christianity.

For agnostics the term Christian existentialism doesn’t really make sense, since after taking this leap the leaper becomes an essentialist. Not that one can’t make this jump, and not that this jump isn’t a good thing to do; that’s up to the jumper. It’s just that the result can’t bridge the gap between the categories of existentialism and essentialism. The term Christian existentialist (or Hindu existentialist or any type of theistic existentialist) combines two fundamentally different meanings: an existentialist life means living without the essence of soul or God in this material world, whereas an essentialist life means living with an essence of soul or God. This is the fundamental distinction made by Sartre, and it is a distinction built into the term existential itself — to exist, that is, to exist alone or by oneself, without aid, intervention, or punishment from some otherworldly essence, whether this be a god, God, Force, Absolute, demon, or angel.

Sartre codified this term in the Modern context, yet even in the Middle Ages people understood that there could be 1. a material or physical world, and 2. an immaterial or spiritual world. They understood the difference between 1. those who believed only in the material world (then called unbelievers or materialists, later also called existentialists) and 2. those who believed that there was an essential or spiritual world shadowing or dominating the physical one (then called believers, later also called essentialists).

Theistic existentialists say they are essentialists and theists at the same time, whereas agnostics say that they experiment with existentialism and theism, one at a time, but not together. They don’t try to experience the essence and yet not experience the essence at the same time. While there’s a great deal of phenomenological overlap between agnosticism and existentialism, agnostics don’t claim to be existentialists. Both are philosophies, and it would be like claiming to be a stoic and a skeptic at the same time. The problem of boundaries is even greater when it comes to existential theists, since they aren’t talking about overlapping philosophies but rather about two fundamental and distinct categories: belief and disbelief.

One might say, sometimes I feel like a stoic and sometimes a skeptic, and likewise I believe at certain moments and disbelieve at others. Yet it’s far more problematic to say that you believe and disbelieve at the same time. Perhaps one way to say I’m a Christian existentialist would be to say I alternate between Christianity and existentialism. Or I inhabit the contradiction of my position, believing and not believing simultaneously. Yet this stance seems rather close to schizophrenia or madness, for it isn’t asserting I live in an existential material world yet believe in another world, but rather it asserts I live in two very separate worlds at once. In one world miracles aren’t possible. In the other world, they are. But they are the same world.

🧩

The Unconvinced

Returning to my chart, I would suggest that there are fewer contradictions in the positions of the unconvinced.

The unconvinced group thinks that belief, doubt, and disbelief are subject to interpretation and re-interpretation, to the historical moment, to one’s philosophical predisposition, to cultural bias, linguistic orientation, etc. The unconvinced suspect they’re right, but they’re not convinced they’re right. As a result, they avoid certainty, whereas the convinced embrace it. In terms of problematic positions — such as those of convinced scientific atheists and existential theists — the unconvinced are less vulnerable: because they doubt their views, any solid idea or any contradictory idea they have will be subject to their own doubts, with the obvious aim of eliminating discrepancies and contradictions.

The unconvinced group is more in line with a generalized search for truth, which makes those with an interest in theology lean toward mysticism rather than organized or historical religion. It also makes them lean more toward epistemology (the study of how we arrive at any truth) than to established schools of philosophy (which tend to explain ways that truth can be established). One might even argue that unconvinced theists, atheists, and agnostics are more aligned with each other than they are with people who share their beliefs yet insist on them. This is perhaps an uncomfortable point for convinced agnostics, given that they stand rather uncomfortably on the same ground of certainty as those who have stepped through the door of belief and those who have slammed it shut. To continue the metaphor, convinced agnostics jam the door open and stand on the doorstep. Unconvinced agnostics see the open door, but understand why some might want to close the door once in a while. Moreover, they like it when the door is open because that allows them to slip from one side to the next.

Convinced theists, in arguing with unconvinced theists, might argue something like the following: Although you can’t prove God, you can nevertheless feel Him. Although you can’t grasp Him by logic and reason, you can nevertheless believe in Him. Why wouldn’t you actively believe in what is by definition operating on the levels of feeling and belief? The convinced theists have a strong case here, and this partially explains why so few theists tend to doubt their belief. One must of course include the psychological and social benefits of a clear belief in an all-penetrating sense of Meaning and in the notion that the ultimate Power in the universe cares about us. In addition, there is escape from sin and punishment, clear moral laws, universal justice, the promise of an afterlife, etc. With all of this on offer, why go so far as to believe it if you don’t commit yourself to this belief?

Agnostics on the convinced side might object that there's no philosophical position, or there’s little value to a position without a firm belief in that position, yet the agnostic thinks the value lies in 1. a realistic view of the universality of doubt, and 2. a stand which allows you to explore all sides, deeply and objectively, that is, without wanting to prove them right or wrong.

Convinced agnostics might also argue that unconvinced agnostics have dogmatically committed themselves to eternal indecision. While convinced agnostics may be firm in their assertion that no one can claim to know an ultimate truth, from a subjective or phenomenological point of view it seems valid to concede that while agnostics don't know an ultimate truth, others might. The convinced agnostic appears to have a point when they argue that the deep skepticism of the unconvinced agnostic is a version of a universal truth, since unconvinced agnostics don’t waver in their conviction that they may be wrong. Yet there are two problems with this logic.

First, it’s difficult to refute someone who says that they might be right or they might be wrong. Even if convinced agnostics proved that conviction is right, this doesn’t contradict the position of unconvinced agnostics, since they already admitted they may be wrong. Their response would be, Yea, we imagined that was the case, anyway. Such a certitude wouldn’t necessarily make them happy, nor make them sad, since what they lose in hope for an essence is countered only by the proof that we’ll never know if they have an essence.

Second, the convinced agnostic’s argument may be a contradiction in terms, for it mistakes the observation of change for the constant of change. Unconvinced agnostics would object, How can you say that everything changes yet then say that change stays the same? The observation of continual change doesn't mean that unconvinced agnostics believe change to be a constant — and this for two reasons. First; saying that change is a constant doesn’t mean that constant is equal to unchanging; rather, in this context it means occurring in every observation, which verifies that change occurs. Second, unconvinced agnostics remain open to the possibility that some things don’t change. Unconvinced agnostics are comfortable with the notion that tomorrow they may believe something else. Like scientists, they take their present knowledge to be contingent, provisional, and conditional. It all depends on the ontological situation of the moment and on the present historical and personal state of their human understanding.

🧩

Next: 🧩 Agnostic Geometry