Russian Horses

Over the Waves - Into the Skies - Into the Fray - Russian Horsepower - On the Hoof, from Minsk to Magadan - Asklepios & Phaeton

🌊

Over the Waves

There are few images more powerful — or more frightening — than that of an army advancing on a city. And there are few natural images more powerful than that of a stampede of horses. In his painting, Neptune’s Horses (1892), Walter Crane gets at both the physical and the mythological power of horses:

At first it may seem odd that Crane depicts waves, which have little to do with solid land, in terms of horses. Yet there are at least three connections. First, the idea works visually, since the horses unfold from the greater body of water onto the sands, thus seeming to roll in a powerful arc from water to land. Their hooves bring all the power of the ocean with them as they land on their native element of earth. Second, both waves and horses are, like glaciers, very difficult to stop. This point will be helpful when talking about how hard it is to stop war. Third, there’s a mythological link between horses and the Classical god of the sea — Poseidon in Greece, and Neptune in Rome. Hence the title of Crane’s painting, Neptune’s Horses. The awesome, uncontrollable power of the ocean has been seen since Classical times in terms of Neptune riding his chariot across the waves, drawn by sea-horses:

This connection may also be implied in Golikov’s image of the troika, where the snow seems like waves, and the wolves seem like sirens — albeit with less attractive bodies and longer teeth …

🌊

Into the Skies

We can also see the horse’s high symbolic status in the horses that pull Helios’ sun-chariot across the sky:

Horses also play a spectacular role in the doom from the skies scenario we find in Revelation. Here, the four horsemen of the Apocalypse bring with them conquest, war, famine, and death.

When the Lamb opened the second seal, I heard the second living creature saying, “Come!” Then another horse came out, fiery red. The one riding on it was permitted to take peace from the earth, so that people would slaughter one another. He was given a great sword.

In the painting below — The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse by Viktor Vasnetsov — the lamb, his Good Book, and a rainbow (at top centre) lie apart from the violence. They are above and behind the clouds, which form a barrier. They are also protected by angel wings, which represent Heaven as well as fierce angels such as Michael or Azrael:

While the horses and their riders symbolize death and destruction, the lamb symbolizes goodness and gentleness, and the rainbow symbolizes peace, or the calm after the storm of violence. The placement of the lamb suggests two things simultaneously: ❧ divinity has no interest in violence and war, and ❧ love and forgiveness may appear small and gentle, yet they’re above, or more important than, everything else.

🌊

Into the Fray

The link between horses and battle is a global one, as we see in the following painting of Krishna’s chariot, which conveys Arjuna into the battle that’s central to both The Mahabharata and The Bhagavad-Gita:

Prior to the battle, Arjuna asks Krishna how he can justify fighting a war against his extended family: “How should we not know to turn away from this sin, we who clearly see the wrong in bringing destruction upon the family?”

Before the slaughters in Bucha and Mariupol, the Ukrainians may well have asked themselves a similar question.

One of the most powerful images of post-war regret can be seen in this image fromThe Iliad, where Achilles and his horses drag the body of Hector across the battle-field:

The sight of his son’s body being dragged across the battle field wears down Priam, the King of Troy. Priam and Achilles then meet, and together they realize that their war is a bloody stupid waste.

🌊

Russian Horsepower

The horse also plays a big role in Russian culture, perhaps because Russia is so large and the need for rapid transport is so great. In some cases, the horse takes on the persona of Russia itself. For instance, on his way back from the Caucasus, Tolstoy writes, “Nothing on the road cheered me so much and so reminded me of Russia as a baggage horse which laid back its ears and despite the speed of my sledge tried to overtake it at a gallop.”

One of the most famous images from Russian literature comes at the end of Part One of Gogol’s Dead Souls (1842). Here, a horse-drawn carriage, or troika, represents Russia’s mysterious, chaotic, violent, imperial trajectory:

What does that awe-inspiring progress of yours foretell? What is the unknown force which lies within your mysterious steeds? Surely the winds themselves must abide in their manes, and every vein in their bodies be an ear stretched to catch the celestial message which bids them, with irongirded breasts, and hooves which barely touch the earth as they gallop, fly forward on a mission of God? Whither, then, are you speeding, O Russia of mine? Whither? Answer me! But no answer comes — only the weird sound of your collar-bells. Rent into a thousand shreds, the air roars past you, for you are overtaking the whole world, and shall one day force all nations, all empires to stand aside, to give you way!

A variant type of symbolic Russian horse is used a hundred years later in Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, where the Devil’s cavalcade of black horses take an apocalyptic flight toward cosmic redemption. In this section of Crisis 22 I’ll suggest that Bulgakov’s steeds add a road to Damascus possibility to the violent and imperial flight of Gogol’s horses. I’ll use this figurative take on horses to ask, Will Russia 🔴 pull on the reins, 🟡 reflect, and 🟢 turn away from its violence in Ukraine?

In his collection of wise sayings, A Calendar of Wisdom (1911), Tolstoy includes this quote from the Buddha’s Dhammapada:

I will call the right groom he who can stop his rage, which goes as fast as the fastest chariot. Other people have no power; they just hold the reins.

🌊

On the Hoof, from Minsk to Magadan

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia was free to join a de-imperialized world. Like Britain after WW II, Russia had centuries of literature and art, music, and culture — but also centuries of bloody triumph over less militarized nations of the earth.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was an actual event in 1989, yet it remains a symbol of fallen tyranny. While Putin said in 2005 that “the collapse of the Soviet Union was a major geopolitical disaster of the century,” most non-Russians see it in an opposite light. From Estonia to Tajikistan, they see it as a release from the Soviet political system and from the communist Empire it controlled.

It’s important to remember how large this empire was. It contained 🐎 the Eastern Block of Europe (from Poland to Bulgaria — not shown on the map below) as well as 🐎 the lands Russia conquered and incorporated into ‘Russia’ over the centuries — Kazan, Astrakhan, Cherkessia, Ossetia, Chechnya, Dagestan, and everything east of the Urals, and 🐎 the Soviet Socialist Republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, Belorussia, Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kirghizistan, and Tajikistan — all of which were allowed independence after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Russians might have allowed freedom to reign around them, and made the type of post-colonial friendship with the previous SSRs that Britain made with the countries of the Indian subcontinent. But instead it chose the other path — holding ever-tightly to people closest to it, sometimes through brutal force as in Chechnya, and sometimes through a combination of political, economic, and military influence as in Belorussia. The culmination of this brutal force is the present situation, where Russia allowed independence to a state — based on 🐎 an acknowledgment of its national identity, implicit in its status as a Soviet Republic, and 🐎 in exchange for it surrendering its nuclear weapons — and then took back their word, arguing that somehow it needed to be saved from itself.

🌊

Asklepios & Phaeton

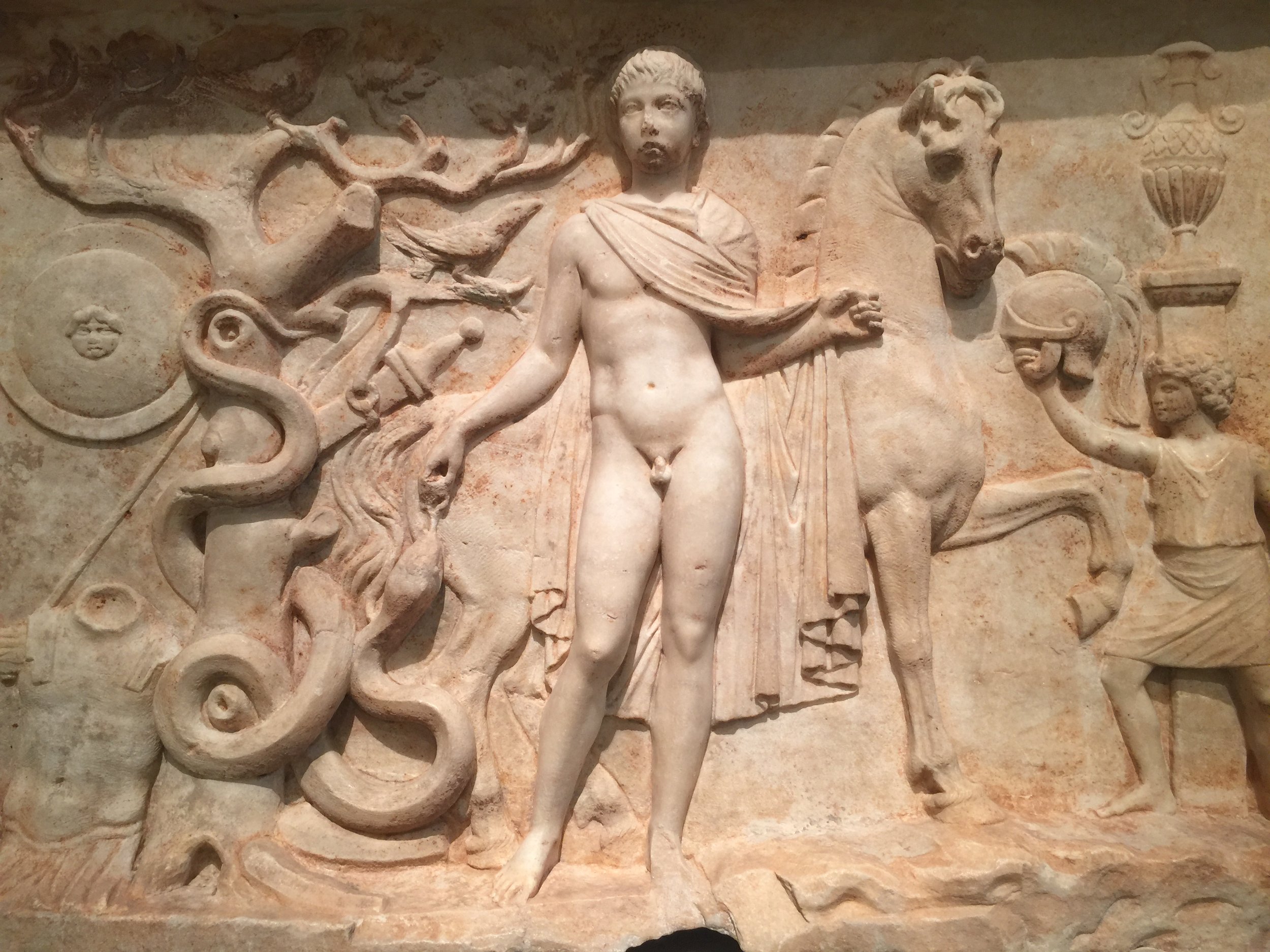

In getting at the terrible mistake the Kremlin is making, I’d contrast two visions: one of peaceful harmony, the other of violent war. The Kremlin could have been like the god Asklepios (the god of healing) leaning “on a staff, around which his sacred animal, the snake, is coiled” (to use the Athenian museum’s description):

Yet instead the Kremlin decided to do what it wasn’t able or supposed to do. In this he resembles Phaeton, the son of Helios. Phaeton is hell-bent on driving his father’s sun-chariot across the sky:

Despite Helios' fervent warnings and attempts to dissuade him, counting the numerous dangers he would face in his celestial journey and reminding Phaethon that only he can control the horses, the boy is not dissuaded and does not change his mind. He is then allowed to take the chariot's reins; his ride is disastrous, as he cannot keep a firm grip on the horses. As a result, he drives the chariot too close to the Earth, burning it, and too far from it, freezing it.

In the end, after many complaints, from the stars in the sky to the Earth itself, Zeus strikes Phaethon with one of his lightning bolts, killing him instantly. His dead body falls into the river Eridanus, and his sisters, the Heliades, cry tears of amber and are turned to black poplar as they mourn him. (From Wikipedia)

We see this (completely avoidable) tragedy in Gustave Moreau’s 1878 painting, Fall of Phaeton. Comparing Moreau’s imagery with the previous image of Asklepios, we see that the healing snake becomes a violent bird of destruction. In Moreau’s version, the snake rises to meet the falling god, as the elements of earth, sky, and sun crash into each other, and as a lion roars down in anger from the skies.

The horses which once conveyed the chariot of light now falls into darkness. Russia, having allowed freedom to its closest neighbour for one short decade, now leads them both to violent death.