Crisis 22

Dead Young Men

⚰️

Not a poem in forty days

Poetry went to the grave

When on November 23rd

Andriy Yurga, a fighter of the “OUN” battalion

Died in battle at Pisky

He came from Lviv, nickname “Davyd.”

Poetry turned black

Wore mourning clothes for forty days

Then it was covered with earth

Then with ash

Forty days poetry sat in the trenches

Clenching its teeth shooting back in silence

Poetry didn’t want to talk to anyone

What is there to talk about?

Death?

(from the start of “Not a poem in forty days,” by Borys Humenyuk, translation by Maksymchuk & Rosochinsky)

⚰️

While the death of young men in battle may be accepted by the Kremlin as an inevitable price of their war against Ukraine, there’s a long literary tradition that argues that this price is too high. Even in Homer’s version of the Trojan War there’s a deep critique of violence. This starts when Agamemnon sacrifices his own daughter so that the Greek ships will sail swiftly to Troy. It peaks when Achilles drags Prince Hector’s dead body all over the battle field, after which King Priam comes to Achilles secretly. The two enemies sit together, lamenting the division, destruction, and futility of war.

⚰️

During those forty days poetry saw many deaths.

Poetry saw trees die.

Those that ran through the minefields of a fall

And never made it to winter.

Poetry saw animals die.

Wounded cats and dogs

Dragging their spilling guts down the streets

As if this were something ordinary

Poetry didn’t know what to do:

Take pity and help them die, or

Take pity and let them live.

⚰️

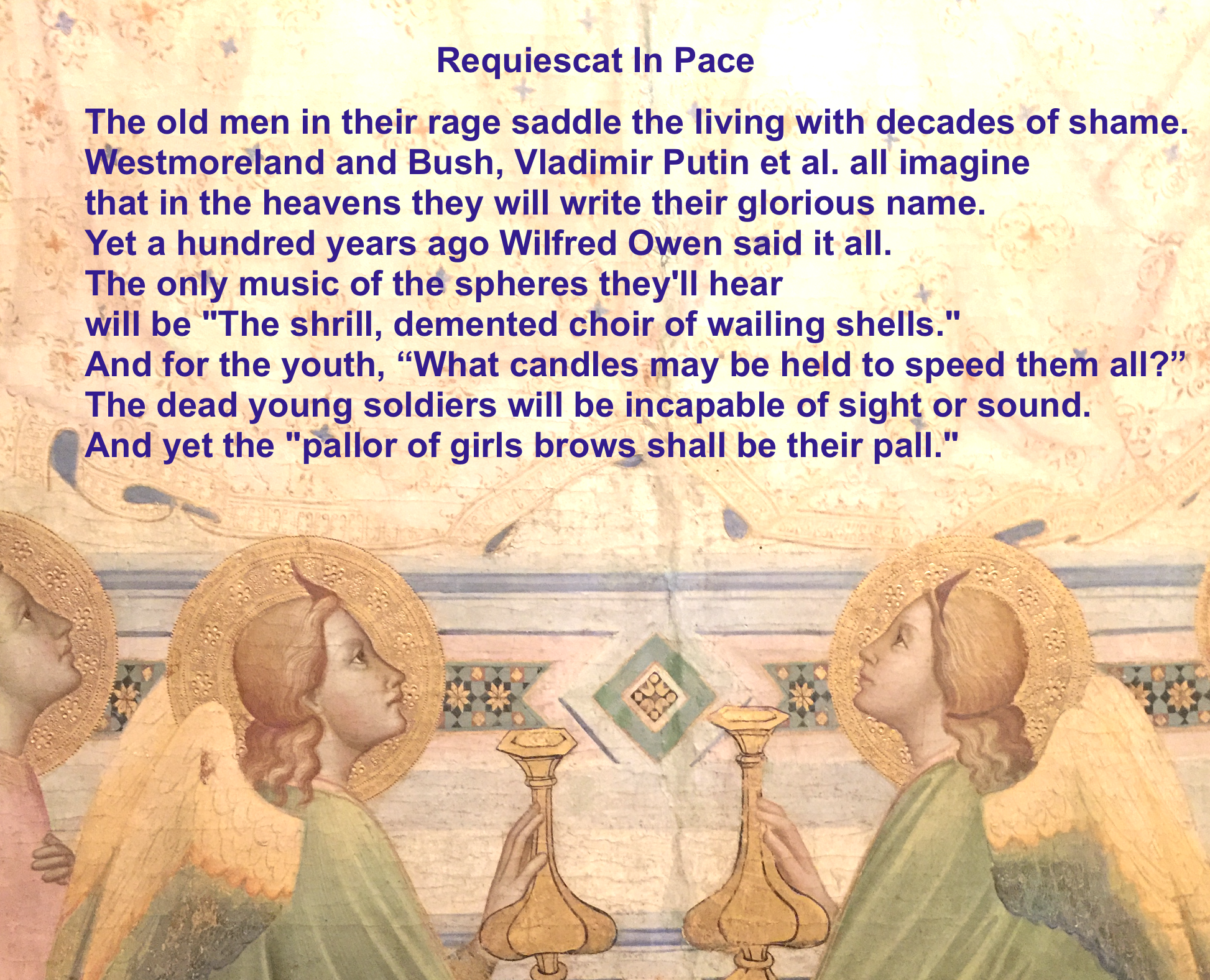

One of the most moving critiques of war was made by the English WW I poet Wilfred Owen. Three of his poems might even be seen as a trilogy on war’s tragedy: “Dulce et Decorum Est” portrays the brutality of fighting and the mental damage it creates; “Anthem for Doomed Youth” depicts a surreal funeral where no one is comforted; and “Strange Meeting” takes the dead soldier into the afterlife, where he meets a man who he calls “strange friend,” who is the enemy he killed.

I am the enemy you killed, my friend. / I knew you in this dark; for so you frowned / Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

The dialogue in “Strange Meeting” is dominated by the murdered enemy, thus allowing, from one point of view, the enemy’s view to win out in the end. The poem also presents a cruel irony: Owen makes a statement about war, yet the statement is about how the dead solider can’t, because he’s dead, tell his story so that others will avoid going to war.

Whatever hope is yours, / Was my life also; I went hunting wild / After the wildest beauty in the world, / Which lies not calm in eyes, or braided hair, / But mocks the steady running of the hour, / And if it grieves, grieves richlier than here. / For by my glee might many men have laughed, / And of my weeping something had been left, / Which must die now. I mean the truth untold, / The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Owen of course was able to write this poem, which is a positive outcome that contradicts to some degree the pessimism of the “strange friend.” Yet in another way, the poem is tragically prophetic: after Owen wrote his poems against war he died in battle a week before Armistice. All those poems he might have written after the war lie, like him, deep in the ground.

⚰️

People are the reason for a house.

Then came the mortar shell.

In autumn, the house used to like the sound

Of walnuts and apples

Hitting the roof.

Now the shell hit the roof.

Then came a rocket from the rocket launcher.

The house leapt up like a girl

Jumping over a fire at the summer solstice.

It hung in the air for a moment

Then landed slowly

But it could no longer stand up straight.

Walls, floors, furniture,

Kids toys, kitchenware, grandfather clock,

All of it bitten by war,

Licked by fire.

⚰️

In his 1918 poem “Dulce et Decorum Est,” Owen argues that we shouldn’t teach our children “the old lie” — that is, the idea that battle is a glorious affair. Owen refuses to finish Horace’s Latin phrase, dulce et decorum est (“sweet and proper it is”) until the end his poem; that is, after he illustrates in disturbing detail how bitter and unfitting war is for the soldier in battle. At the end of the poem the phrase Dulce et decorum est / pro patria mori (“sweet and proper it is / to die for your country”) is preceded by three words: “the old lie.”

Dulce et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime...

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

⚰️

Owen’s “Anthem for Doomed Youth” (1917), might be seen as war’s next stage, the effect of the old lie: the funeral.

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, -

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of good-byes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Owen’s vision of the soldier’s funeral isn’t pervaded by a glorious notion of afterlife. Such a notion is for him as illusory and self-serving as Spenser’s claim to write the name of his mistress in the heavens (Spenser tells his mistress, “My verse your virtues rare shall eternize, / And in the heavens write your glorious name”). Instead of seeing soothing candles and hearing heavenly music, the attendees at the soldier’s funeral hear “the monstrous anger of the guns.” That is, they hear the very things that their brothers and sons heard before being blasted to death.

⚰️

⚰️

Poetry saw people die.

Poetry put spent bullet shells in its ears.

Poetry would rather go blind

Than see corpses every day.

Poetry is the shortcut to heaven.

Poetry sees into the void.

When you fall

It lets you remember your way back.

Poetry went places

Where there isn’t place for poetry.

Poetry witnessed it all.

Poetry witnessed it all.

— final lines of “Not a poem in forty days,” by Borys

Humenyuk, translation by Maksymchuk & Rosochinsky

⚰️

Next: Chapter 4. Waking Up: 🌒 With Open Eyes