Gospel & Universe ❤️ Three Little Words

Locked Into This World

Texts - Dreams

❤️

Texts

Locke’s notion that we’re products of our senses is a highly practical one. It’s for this reason that the zealous priest may well despair when he reads about it. The very eyes he uses to read his Bible, and the finger that turns the page, seen by the eyes, tells him that here’s an argument that his Holy Book cannot ignore. No matter how much he reads about sacred mountains and airy skies, he knows he’s only sitting in a chair, and that the chair isn’t some throne in the sky but instead sits on a British India carpet, and that the carpet lies on the wooden floor of a house. The windows of the house might be used as metaphors for open skies and infinite journeys, but usually they’re used to look outside and see whether or not it’s raining. It’s been raining for 40 days and 40 nights. The priest wonders if the streets will have little rivers in them and if he’ll need to put on his rain boots.

We live in the real world, not matter what it says on the page.

⛵️

Dreams

One of the problem agnostics have with dogmatic religious people is that they pretend to tell us things they can’t possibly know. For instance, what happens after we die. Agnostics can’t imagine how they can even imagine they know this.

It's hard to imagine death because everything with which you imagine it is a function of your life. Your brain thinks about a different form of existence, but your eyes and your fingers can’t imagine it. You’ve never not breathed, or at least not that you can recall. In order to understand it, you have to use something else, for the experience of the afterlife is clearly not at hand. So you enter the realm of analogy and metaphor, and the metaphor that makes the most sense — from your toes to your cerebral cortex — is the dreaming we experience in sleep, the most famous example of which is contemplated by Hamlet:

To die, to sleep,

To sleep, perchance to Dream; aye, there's the rub,

For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause.

Hamlet’s statement is wonderfully agnostic: the possibilities of theism and atheism are both latent in the word perchance. Perhaps we sleep and dream (die and live again). Or perhaps we sleep dreamlessly (die without an afterlife).

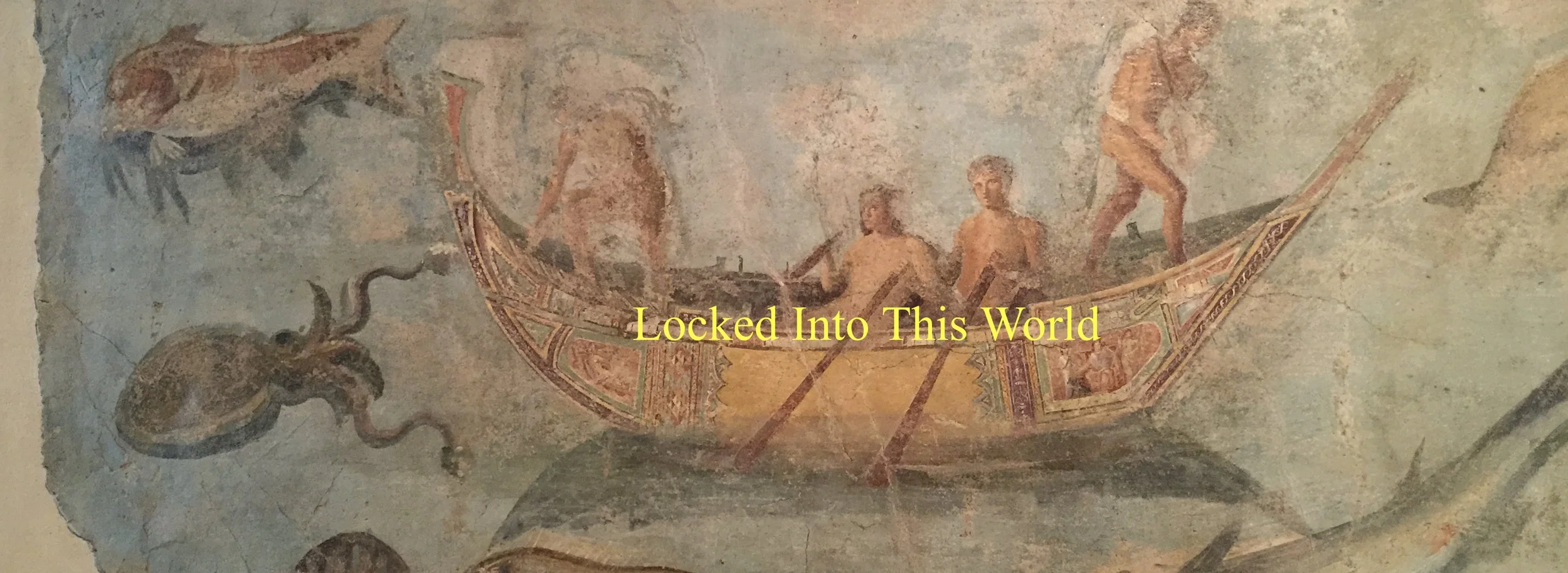

But for the sake of argument, let’s say that we do dream, that we do step across the border into that “undiscovered country, from whose bourn / No traveller returns.” So you imagine yourself going to sleep and dreaming, except that you don't know what it is that you're suppose to dream. So you choose the old dream, the one that’s been etched into you by Art and Literature since Sumer and Greece — that is, the ferryboat rides of Urshanabi and Charon. So you follow your cultural orders, line up on Charon’s dock, and buy a ticket for the other side.

You cross the River Styx, your body dwarfed by Charon, as in the painting below by Joachim Patinir, which you’ve cropped and brightened, adding a touch of hallucinatory surrealism to your afterlife adventure.

You look over to your left and hope that Charon is just navigating the current, making a sharp right turn — onto the via destra and the bright little cove with angels waving you onward with Ave Maria playing in the background. You worry however that he’s turning your little boat away from the bread and song of the angels, taking la via sinistra instead, toward the darkening river that slides beneath a castle dungeon, across from the three-headed dog, beneath the burning towers and tortured limbs.

You can’t help noticing that this dream of the afterlife is limited and dichotomous. What about the other options? What about being reborn on a distant world? Where are all the things that made life worth living? You try to shake off these thoughts because there would be no end to other worlds and to things that might make life worth living again. The conjectures would go on forever. Apsaras and gandharvas, four houri girls, Montana Wildhack. Visions of Paradise. The Rg Veda:

‘Crazy with asceticism, we have mounted the wind. Our bodies are all you mere mortals can see.’ He sails through the air, looking down on all shapes below. […] The stallion of the wind, friend of gales, lashed on by gods – the ascetic lives in the two seas, on the east and on the west. He moves with the motion of heavenly girls and youths, of wild beasts. Long-hair, reading their minds, is their sweet, their most exciting friend. (10.136)

But you’re hardly crazy with asceticism. You live in a regular apartment, in a district of Vancouver they call South Granville. You like looking at the girls from the coffee shop on the corner, and you like to play golf. So you concentrate on the afterlife dream that has been laid before you by your dichotomous forebears.

Forget about the Vedic poets on the banks of the Saraswati. Forget about Zhuangzi and his butterflies.

So you imagine waking up in an other world of pink clouds and harps at the sound of your alarm clock. Your eyes are refreshed with a Rip Van Winkle sleep. You look forward to what John Donne put so optimistically: “One short sleep past, we wake eternally / And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.” You repeat Dante’s magic formula, this time in the present tense: Nel ciel che più de la sua luce prende son io / In the heaven that takes more of His light am I.

But the space around you is still dark. You remember buying a ticket for the boat, and thinking that you were going to be dipped in the River of Oblivion. But you don’t feel refreshed at all. You can’t even remember the boat, or the water flowing through your hair. And it’s the same old you.

You look over to the clock and all it says is 3:00 AM.

⛵️

Next: ❤️ Que Sais-je?