Fairy Tales 🧚 Black Diamond

Alicia

The book Beatrice read from most often was Alice in Wonderland. Well, she couldn't exactly read the book, since someone had hollowed out the pages. This wasn’t a problem however: she had long since memorized the story and could expand upon it with incredible verisimilitude. Besides, the hollow in the book made a great hiding place for rice crispy squares and thick slices of angel-food cake.

She was always sure to slip in a number of Dare cookies. She made Baldric swear before eating each one that he would muster the courage to fight the forces of black magic and selfish ingratitude. To consolidate her position over the boy, she told him that books were the stuff of his being, that what he ate was what he was, and that what he read was what he ate. That was on one level. On another, it meant that Alice had fallen into the hole in the book and that it was his mission to bring her back. In urging her son to chivalric action, she quoted from Don Quixote, leaving out certain parts of the narrative, so as to make it more inspirational:

His mind grew full because of what he read about in his books — enchantments, quarrels, battles, challenges, wounds, wooings, loves, agonies. Everything he read about was true, and no history in the world had more reality to it. Then he came upon the notion that he should become a knight-errant and roam the world in full armour on horseback, in quest of adventure. He should put into practice everything he read, righting every wrong, and exposing himself to every kind of peril and danger, from which he was sure to reap eternal fame.

But Don Quixote didn’t mean more to Baldric than the price of cow feed on the Chicago grain market. It was only the thought of resurrecting Alice’s face from the abysm of missing print that gave him the sense that he existed in this world for a reason. When he thought of Alice’s sweet countenance and nimble limbs, he couldn’t agree with his father that he was only a walking shadow that strutted and fretted for an hour or two upon a stage somewhere north of Edinburgh. No, he wasn’t just a poor actor in a tale of mystery and imagination told by a furious idiot.

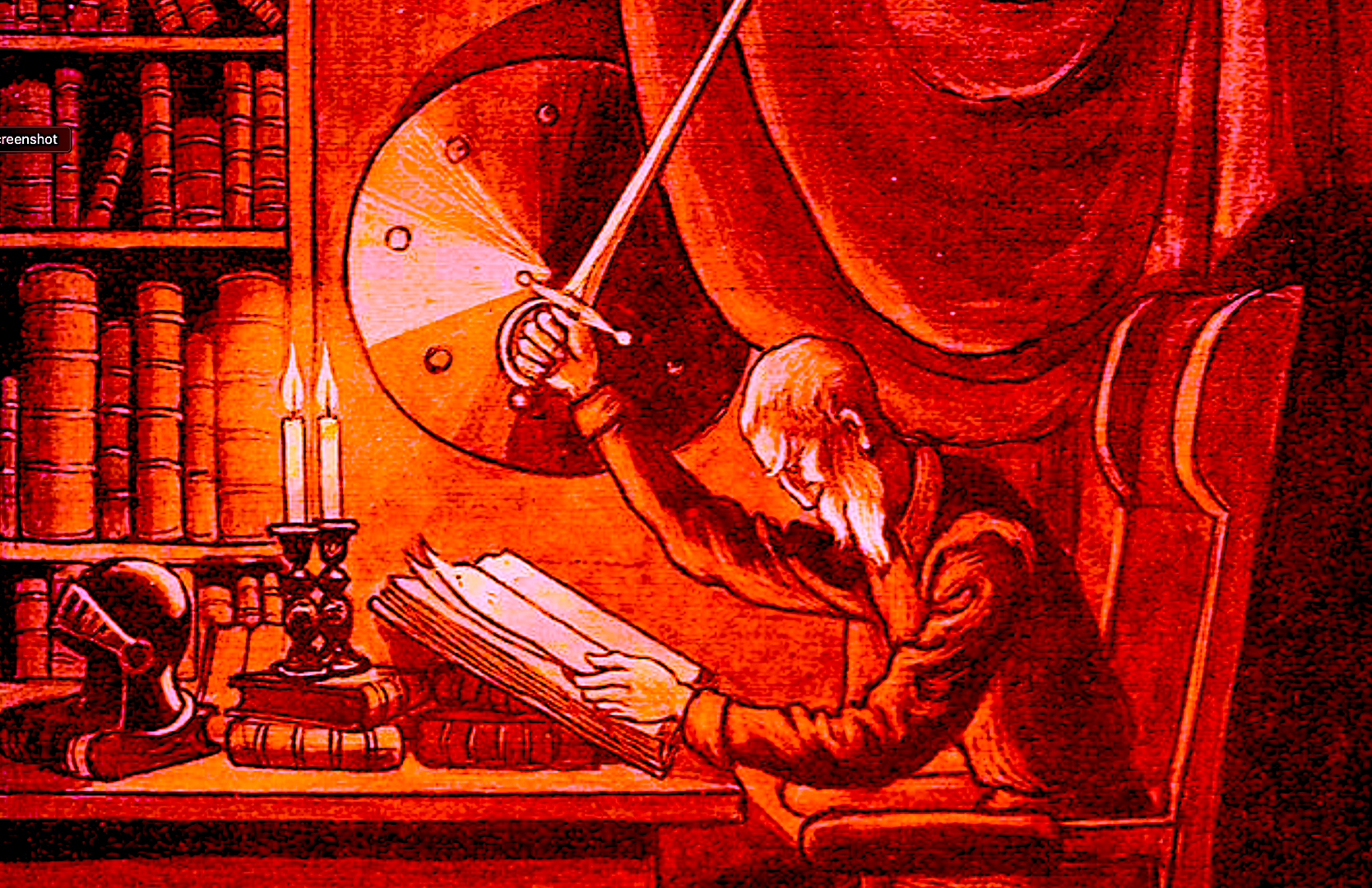

Idiot or no idiot, Baldric couldn’t stop thinking about Alice. This tendency of his mind to wander in here direction infuriated Antonio. He therefore decided to steal Beatrice’s idea of seducing his son’s mind with food. As soon as Baldric came home from school, he made him what he called Richard Alpert biscuits and Carlos Castaneda tea. While his son was consuming these, Antonio quoted passages from Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. He used this version (rather than that of Goethe) because it didn’t contain false notions of redemption, and because it brought the reader directly and unequivocally to Hell, which Antonio insisted was everywhere, despite Tomás de Torquemada’s claim to the contrary.

The effect of the tea magnified the contents of Marlowe’s tragedy: Baldric saw hideous black vapours sweep up from a dungeon in his mind. He saw a Tyrian purple corridor set with traps for rodents and snakes. A streak of lightning bolted through the grey fog of his thoughts and smashed onto the wall of his consciousness in a thousand horrible images. To wash down the bitter dregs of tea at the bottom of his cup, he was forced to drink dark brown mead that fizzed and popped. This strange brew made him imitate his father, who was performing druidic rites at the high table in a mead-hall filled with Anglo-Saxon thanes.

Baldric barely made it to dawn, by which time the dancing dregs at the bottom of his cup withered into dust and stopped laughing in his brain. The three witches who had danced around his room fell asleep and then toppled into their own cauldron like so many eyes of newt. If this was true, who would be left to stir the cauldron and bring Macbeth to his fatal vision? Looking at the ebony shadow that floated toward him, Baldric didn’t have time to consider this question. A black cape swept across his bedroom, dark frills arcing into the air like a swarm of vultures.

As Antonio twirled downward, he invoked the paranymphs of Baudelaire, ordering them to entwine themselves with les sepents qui dansent. He declared that this was the most beautiful love that Don Juan had ever conjured.

Antonio landed on top of Baldric’s bed with a plop, suddenly despondent. He was tired of Latin fantasies and wanted the real thing. So out of the bedroom he trotted like a fox, and made his way to the chicken coup in the pantry. Yet en route he tripped over a gossamer-thin string, and fell into a deep well padded with goose down. Baldric then heard the clucking, soothing murmurs of his triumphant Mother Goose.

As Beatrice flew into his bedroom she seemed twenty miles away. In the next scene, she was shaking a wand or crowbar in the direction of a wolf, who had climbed out of his hole and was threatening to dismantle a voodoo doll in order to punish womankind for its original fructifying sin. Neither Baldric nor his mother knew what to make of such a threat, although Baldric later had a strange dream in which he met a white-faced girl who looked like a doll. Her enamel skin was milky, and her dress had birds that made it look like she was about to fly away. Unlike his father, Baldric had no desire to punish the doll. He just wanted to put her in his mother’s figurine cabinet and look at her every now and then.

In a puff of smoke his father was gone. His mother flew across the battlefield of hookas and magic lamps to perch on the foot of his bed. In the next cut, her nose was the only thing on the screen, magnified a thousand times into a beak of staggering proportions. It opened, cackling forth poems by Bobby Burns and Percy Shelley. From these she moved on to the romances of Sir Walter Scott, which extolled the virtues of Liberty, Chastity, and the Ecstasy of a down undergarment.

The drugs finally wore off around six in the morning, by which time his father’s chickens had gone home to roost and his mother had taken off her spectacles and thanked the Lord they had survived to see one more day. She then kissed her son goodnight and slipped a book under his pillow.

Although Baldric was in desperate need of sleep, he grudgingly accepted the latest volume and ploughed through it in the few remaining hours before breakfast. There were already 50 books beneath his pillow, yet he had a strategy: if he read one book and one sentence per night, then in sixty years the pillow would descend to within a foot of his mattress and he could get a decent night’s sleep.

🧚

Sleeplessness caught up with Baldric by the time he entered grade eight. He found it particularly difficult to keep his eyes open in math and biology, where his teacher was telling them about ratios, gradients, right angles, split ends, and square roots. Baldric couldn’t honestly say he’d seen a plant with square roots before. But then again he’d never seen a unicorn either, and his mother insisted that such a beast could make all your drams come true.

Even if he went to China where life was upside down, he doubted he would find a square root under the ground. To Baldric’s horror, his teacher also confessed a knowledge of cubed roots, which was even more unlikely, although Mother Nature was probably confused in the wake of Mao’s ambitious backyard plots.

The final straw came when his teacher insisted on calling numbers and letters formulas, as if they were mathematical spells instead of mere prison terms. These formulas were supposed to embody abstract truth, idioms or axioms, Baldric couldn’t remember which. Either way, Baldric was highly skeptical about what his teacher was saying. Ironically, skepticism was precisely what the math teacher was aiming at, albeit through multiplication, subtraction, and long division.

To a sleepy and confused young boy these formulas just sounded like a bunch of numbers and letters thrown together, as one might mix apples and oranges — which Baldric shouted out was against the rules! This outburst stopped the math teacher in his circular track, for he couldn’t deny that he had often eaten such fruit salads at home. Pondering this threw him into a fit of existential despair, followed by an urge to join the Methodist choir. Gradually, he began to teach less algebra, and spent more class time trying to balance a single fallen angel on the pin of his head.

As a result, math lectures were more perplexing than ever. What with no sleep, obtuse angles, squared fruits, carrot cubes, and cubed beets, Baldric couldn’t stop his head from plummeting to his desk. Much the same thing happened during History class, except that one day as he was about to lose motor control of his neck he saw a golden light reflect off the skin of a real honest-to-God angel.