Crisis 22: Politics & Literature I

Fog & Shadow

Fog - Shadow - Koch’s Year - 007

🟢

March 2025

Fog

In the opening pages of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Anna Pavlovna asks, Dites moi, pourquoi cette vilaine guerre?” / Tell me, why this nasty war?

Anna is asking (in 1805) why Napoleon is waging war in Europe, yet the same question can be asked today about Russia in Ukraine. Indeed, why? And where do we start in trying to understand what’s going on?

The simple truth might be a good place to start: the Kremlin has chosen to invade its neighbour. Why? ❧ Perhaps so that Putin can stay in power. This isn’t a stretch, since he rode to power on his war horse in Chechnya decades ago. Yet there are other reasons. Let’s start with the most preposterous one — that is, the one the Kremlin gave on the eve of its invasion: ❧ Nazis are controlling Ukraine, and the Russian Army is on a special military operation to root them out. Perhaps the Kremlin would also have us believe that the little green men who took over Crimea in 2014 weren’t Russian, but Martian. In the same absurd universe of fantasy facts, the word operation means the same thing as war. And yet, I doubt that the average Russian believes in making alliances with Martians or in altering the meaning of words.

Three more realistic reasons come to mind, namely that Russians ❧ fear NATO, ❧ despise the West, and/or ❧ want to return to the glory days of Empire. Yet once we get into these reasons, it’s hard to separate what Russians think from what they’re allowed to say. This is no mean distinction in a country where to defenestrate is an active verb. Journalists, opposition leaders, and whoever suggests an alternate reality to that of the Kremlin, are silenced one way or another.

It’s here, in the muddle of intentions seen through the fog of war, in a global climate of catastrophe and torn loyalties, that my little project comes in. While I can’t give a clear answer to Anna’s question Why this nasty war?, I’ll take a look at it from a variety of literary, cultural, and geographic angles. Hopefully this type of exploration will help people in the present, and also serve as a sort of cultural-political diary for the days when this crisis is in the past.

For the moment, everything is up in the air and it’s hard to know which questions to ask. So perhaps it’s best to admit that my little study isn’t likely to lead to a clear picture of what’s going on. Yet hopefully it will lead to a more informed and more fully humanized understanding. Not so much an understanding of what in the world is going on than a range of understandings about what is going on in the world.

My understanding is largely coloured by my agnosticism, a philosophy in which we can’t be sure if there’s a God or not. Likewise, I don’t think we can know about what’s going to happen in Ukraine, Russia, and global politics. This is why I emphasize methods of coping when fumbling in the half-light, ways of moving forward despite being surrounded by fog and shadow. My approach is a geo-political version of negative capability, which Keats defines as the ability to remain “in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Of course we’ll keep searching for fact and reason. But we don’t need to be irritated by this search. Instead, we can learn and be stimulated along the way. We can look for answers in the richness of human culture, whether it’s Russian or Ukrainian, American or British, Indian or Chinese, Australian or Indonesian. This richness makes the search less one of irritation and more one of discovery and depth. The irritating problem remains, but an enriched or refined search for solutions can help to dissolve the irritation. One might call this the balm of art, the wisdom of history, the relief of geography, the solace of culture, the consolation of philosophy, or the persistence of globalism.

🟢

Shadow

Take for instance the cultural expression of the Indonesian puppet theatre. It may seem a world apart from the Ukraine crisis, yet it supplies a paradigm that will come in handy psychologically by helping us process the angst of uncertainty and obscurity. It will also come in handy politically by giving us a medium through which we can puzzle out the Kremlin’s hidden manipulations. Finally, it will help us counter the Kremlin’s absurd claim to lead the Global South against the Evil West. If we understand more of the Global South and the way it articulates and explores politics, then we’re less likely to let Russia define Western liberal democracy on our behalf.

The Wayang Kulit, or puppet shadow-theatre, is used in Indonesia as entertainment and also to mark special occasions. Yet most crucial here is that it’s also used to interpret politics. Indonesians see in it local politics, national politics, and international politics, mixed in with the cultural and religious fusion that’s characteristic of their national identity.

Wayang Kulit literally means Shadow (or Imagination) Leather. The flat stick-puppets are made of leather, and the audience sees these leather puppets as shadows or imaginary figures on a silk screen. In this shadow-theatre, puppets who represent Good and Evil, Falsehood and Truth, Left and Right appear in the guise of darting, fugitive outlines, cast onto the silk screen by the flickering light of a kerosene lamp on the other side of the screen.

The figures of the Wayang operate within the syncretic Indonesian realm of folk tale, contemporary culture, and epic — especially the great Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, with their focus on duty and the conundrum of wanting peace yet waging war. The puppet-master, or dalang, creates the flickering images of these figures from the other side of the screen. The dalang also narrates stories, sings, makes commentaries, and oversees the choir and the jangling flow of the gamelan orchestra behind him.

The motives of the Wayang figures are sometimes obscure and sometimes glaringly obvious. The figures and what they represent disappear into the deep shadows of the Javanese night or fly upward to the intense light of heaven. Watching from the audience side, we’re curious to see behind the scenes, behind the flitting images on the screen. We want to see who’s running the show.

🟢

Koch’s Year

In Christopher Koch’s novel The Year of Living Dangerously (1978), the Australian journalist Guy Hamilton tries to find out what’s happening in Jakarta behind the scenes. Who’s holding the reins of power, and how will the drama unfold? Hamilton tries to enter the hidden corridors of power in the tumultuous “Year of Living Dangerously,” which is President Sukarno’s name for 1965. As puppet-master, Sukarno is tilting his country toward China and the Indonesian Communists, yet the Muslim generals don’t want to live in a Chinese-style State that denies the existence of God.

Two-thirds of the way into the novel, Hamilton travels into the hills of Western Java looking for information about the strength of the Communist Party. On the outskirts of Bandung he comes upon a humble performance of the Wayang Kulit.

Hamilton hears the dalang singing and commenting, and he realizes that this dramatic performance is a complex way of understanding the world. Yet he hasn’t spent the time necessary to understand the Wayang. As a result, his understanding of the country is a limited one:

People pressed close to watch the sacred theatre's mysteries; but Hamilton drifted away to the other side of the screen, to the magic side, where only the filigreed silhouettes could be seen, their insect profiles darting, looming into hugeness, or dwindling to vanishing-point. Their voices chattered things he could never understand, rising into the warm dark: but the schoolroom rapping on the puppet-box commanded his attention. Standing behind solemn elders from the kampong, for whom chairs had been placed on the grass, he seemed to be watching the deeply important activity of dreams.

The dalang was singing. His wailing, almost female voice climbed higher and higher, while the little drum pattered on underneath, and the gongs bubbled. On one wavering note, his voice was drawn out and out, until Hamilton, transfixed, seemed to see it like a bright thread against eternal sky; until it connected with Heaven. What was the dalang singing about? He would never know.

Koch’s treatment of the Wayang shows us another way of looking at the world. Although Koch doesn’t say it directly, he suggests that we ought to pay attention to foreign paradigms and ways of thinking. This attitude might be very helpful to the West if it wants to understand and cooperate with Asia and the Global South, and if it wants to counter Russia’s claim to speak for the multi-polar world.

🟢

007

Koch’s treatment of Sukarno’s 1965 also includes many insights into the Cold War, including the shadowy operations of China and Russia. On the outskirts of Bandung, Hamilton is on the verge of starting to understand something of the Wayang, thanks to a friendly villager who explains the plot. Hamilton feels the kindness and humility of the man next to him, and he smells the spicy scent of the clove cigarettes in the night air. It’s an almost magical moment. A moment of revelation, the skein of the East becoming translucent, and he, a tall Australian, about to understand how it might all come together. Yet at this pivotal moment Hamilton allows himself to be turned from the magic screen by Vera, a Russian agent who then seduces, drugs, and interrogates him in a nearby colonial Dutch hotel.

At several moments in the novel, Koch asks his reader if he believes in the spy-thriller scenarios of James Bond. Koch wrote Year in 1978, when such scenarios were a big part of Western culture. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the scenarios faded somewhat, the Russian spies often replaced by Russian mafia dons and Islamic terrorists.

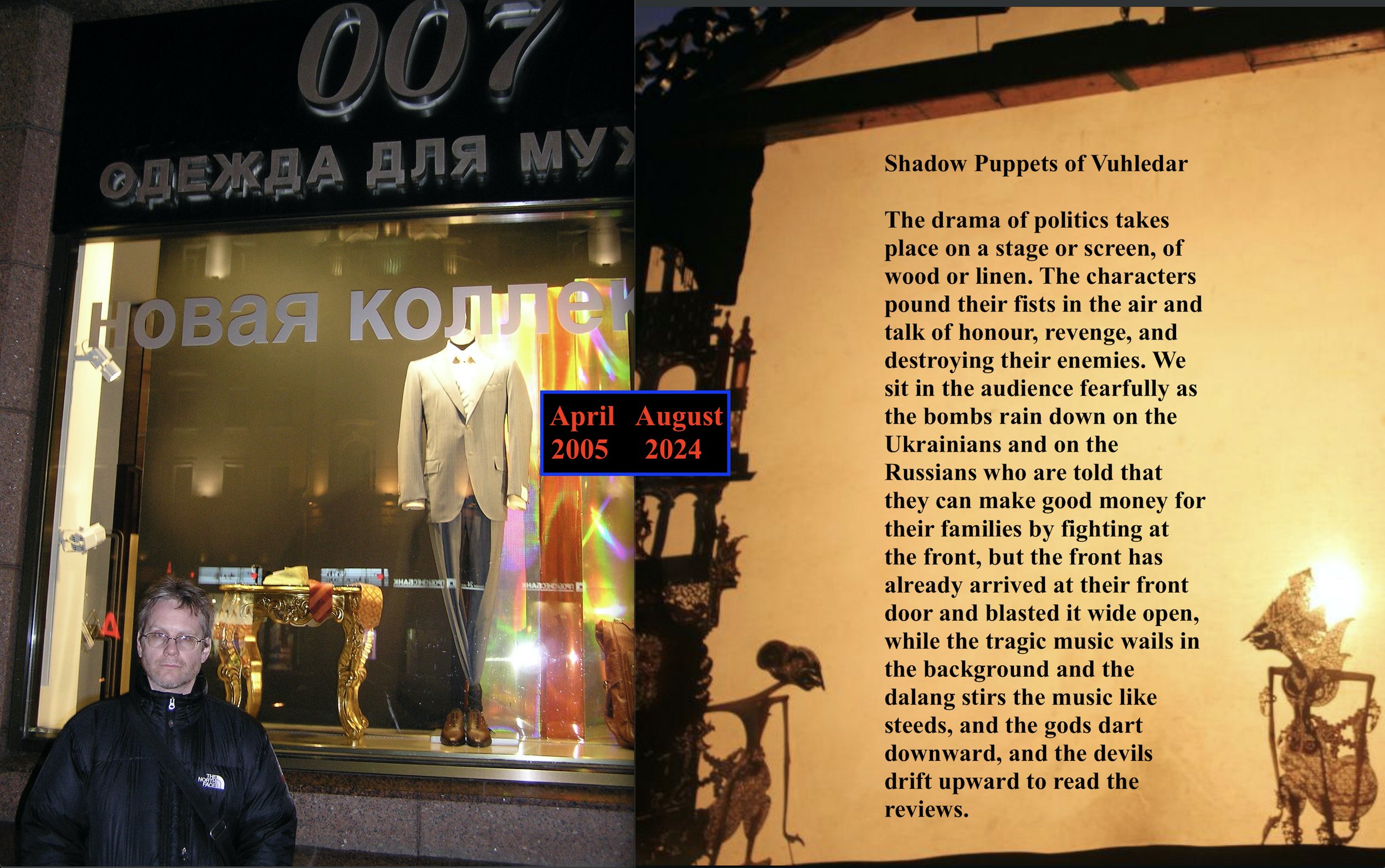

As a tourist in Moscow in April 24, 2005, I thought, What an irony! What an anachronism all this James Bond drama! Now 007 is used to sell fancy clothes! But then came 2014. And February 2022…

Back in 2005, my experience of Russia involved trains and rented apartments, Georgian restaurants and hockey rinks. The 007 lettering above the shop window (on the left side of the graphic above) was a comic anachronism, a sort of fairy tale. It came from an old spy novel rather than real life. Why worry about James Bond and Russian villains when the communists were gone?

Yet that sense of anachronism turned out to be an illusion. Paradoxically, my fantastical, poetic take on today’s war (on the right side of the graphic) has become far more real. Good and evil have taken on the dimensions of the Indonesian shadow-theatre, with its mythic meanings, its moral ambiguities, and its apocalyptic battles. Reality became fairy tale, and fairy tale became real.

Yet happily ever after is as elusive as ever. In the old Ramayana story, the good monkey army (led by Hanuman) travels to Lanka (with Rama, an incarnation of Vishnu), defeats the demons, and frees Rama’s wife Sita:

If only this were the case today! Unfortunately, what we’re seeing is closer to the scenario in the Mahabharata and Bhagavad-Gita, where cousins are lined up to do battle against their own cousins. Seeing this, the hero Arjuna turns to his charioteer, the god Krishna (referred to below as Janardana, the Protector), and tells him that he doesn’t want to kill members of his extended family. They may be greedy, destructive, and treacherous, and he may have to fight them, but isn’t killing sinful in any context?

In the middle of the battle-field, filled with angst, Arjuna must reconcile himself to the imminent slaughter.

🟢

Next: ☮️ Glaciers & Novels