Transparently Multicultural

~ for Alain Bashung, son of an Algerian father

he never knew. R.I.P., mon vieux ~

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

There was nothing Anaïs loved more than traditional Arab men. She loved their thick coily hair, their olive skin shaved close from under their eyes to their lower jaws. But what Anaïs loved most was Ahmed’s beard, his long black flowing beard. It started at the lower edges of his chin, making him look like Abe Lincoln, Henry David Thoreau, or an old-fashioned jihadi from the eastern hills. Ahmed liked to shave his upper lip, just as the Prophet recommended. With a twinkle in his eye he would quote the old Hadith, “Trim closely the moustache, and grow the beard, and thus act against the fire-worshippers.”

With a wide-eyed innocence that her father could scarcely believe, Anaïs told him about Ahmed’s culture, his family, his big strong hands, and his full dark beard. At 43 years old, he was the love of her life.

Because his daughter was only seventeen, her father raised both his eyebrows.

Anaïs imagined his gesture to be a mix of surprise and curiosity, so she told him, “Behind every immigrant there’s a fascinating story, full of adventure and poetry. But they probably didn’t teach you that in military school.”

Her father stared at his daughter, slightly narrowing his eyes.

“Yesterday Ahmed and I were leaning out the window of his apartment on Rue Botzaris, looking out over the lake in the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont.”

“He told me about his life in Algeria, and about how his father got caught up thirty years ago in elections that weren’t really elections. The generals and the West had betrayed them again.”

Her father frowned, although not for exactly the same reason he’d previously raised his eyebrows or narrowed his eyes.

Anaïs pretended to take his expression as a sign of deep thought, and continued. “Ahmed said they promised democracy and tolerance, but couldn’t tolerate a vote for Islamic law. As if they didn’t live in a Muslim country! He said that Putin and Wagner would be better than the French.”

Her father froze. He was determined not to make any movement that his daughter might misinterpret as consent.

“By the late 90s things got so bad that his family had to flee. The French were brutal in their indifference, worse than in the 50s.”

His face unchanged, her father pressed his toes downward inside his shiny black leather shoes.

“After the generals shot his father, his mother traded her jewelry for a small boat, grabbed her three children, and sailed for France.”

“Ahmed’s eyes got misty when he told me about the first time he saw the Seine from the Pont Neuf. His father had gone to school in Paris, and had told him about his days at Nanterre, drinking to all hours of the morning, going out with French girls, joining political action groups, and learning the truth of the Qu’ran.”

Her father thought about all those Greek family dramas and how they ended tragically. It was all a pretext — the golden apple, Agamemnon’s sacrifice, the high walls of Troy — but what made sense to him was the pathos, the tortured promise of good intentions. But these intentions jammed up against the facts, and always went awry.

“Ahmed’s life in Ksar el Boukhari had been chaotic, as his father moved them from one broken-down house to the next. But now, looking every day at the lake from five stories up, he can relax. He can imagine what his father felt.”

Surely people understood that Agamemnon loved his daughter and that her sacrifice was necessary.

“I told Ahmed he was lucky, and he shrugged. I pulled on his beard and insisted he was lucky, then let my hand fall over my breasts to my belly-button, to show him why.”

Surely they didn’t think Agamemnon was a heartless man, whatever his differences with Achilles. And yet they never focused on the tears he shed on the beach, watching them drag her body to the fire. They recorded it as if he stood there, dumb, while his evil wife in her harlot robe pretended to weep.

“I told him his beard was a lucky charm, a talisman. Like Samson’s hair.

“He looked at me with his big black eyes and said that I was right: ‘The first time I noticed it growing on my chin I was on the Chelif River, floating down from the Saharan Atlas to the coast, and from there into the Mediterranean. My beard made me think of the beard of my dead father, black speckled with grey.’

“He even quoted Alain Bashung”:

“Ahmed said that when he was living in Algeria he felt rootless. It didn’t help that he was a teenager and they still taught Camus at the lycée. Initially, he agreed with his teacher: his self was like water slipping through his fingers. But then as he and his family floated down the Chelif River, he saw that his self was a real solid thing. Together with his mother and his two sisters, they slipped down the water, and their hands were empty. Now he can joke about it. He says that no one in their family had black feet, so they couldn’t relate to Camus after all.

“Ahmed has an amazing sense of humour, even in the face of everything the West has done to him. He turns it into a running joke. Whenever we’re in bed he twists his legs to show me the soles of his feet. ‘See, no pied noir!’ He also says that European existentialism is a joke. It never gets at true experience. Phenomenology is a waste of time. Only the living Word of God can redeem a dead culture. And the Qur’an is the living word of God. But only the oppressed can hear it.”

Her father steadied himself by putting his right arm on the living room credenza. His hand lay on top of the varnished 17th century Italian wood, as if relaxed. He tried to imagine how his world might have looked in a painting by Vermeer, with his obedient wife all dressed up, his prim daughter mute as stone, and his hunting dogs ready at the leash.

On her thirteenth birthday, he gave Anaïs a gift of two pearl earrings. From then on he called her ‘my girl with the pearl earrings.’

She used to be so calm and agreeable. She used to radiate light everywhere, even in the pitch dark. Her eyes were so direct, as if they were a translucent medium for her open soul.

She still had the same flawless skin as Scarlett Johansson in the film, so smooth and white that an artist would give his eye teeth to paint it.

He thought to himself, ‘The movie got it right: the wife would take one look at her beauty, the pearl earrings against her flawless ivory skin, and go insanely jealous. And yet the whole thing would be settled without bloodshed, in a rational way. In a Dutch, Northern way.’

He didn’t think of his daughter as an angel, and he imagined that she’d get caught up in all sorts of sordid affairs.

But they’d be Northern affairs, ones he could understand. Affairs of money and sex — not alien politics, faraway cultures, and patriarchal codes that he couldn’t decipher, yet of which he nevertheless seemed to be the biggest culprit.

His daughter lauded Algerian culture, yet did she really understand it? Ahmed told her that Muhammad brought women freedom, back in tribal Arabia. Yet was the 7th century the right historical reference point? Maybe in the Atlas Mountains, or even in Algiers, but in Paris? Her father imagined the patriarch of an old Algiers family looking away from Delacroix’s image of the French Revolution, thinking ‘How horrible! Breasts in the open air!’

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

“Ahmed went downstream with his family past Chlef and into the Mediterranean. From there they drifted with the current that took them them past Algiers to Lampedusa. From there they made it to Sicily, Marseille, and finally Paris. Looking down into the Seine from the Pont Neuf, he knew he was finally home.”

Anaïs told her father that Ahmed’s story made her feel reborn, as if she was living a new life altogether. “The same year Ahmed completed his journey across the Mediterranean I completed my own journey, from my mother’s fallopian tube to her vagina, and out into the world.” Her eyes were wide with wonder.

Her father winced. He didn’t mean to do it, but he couldn’t help it. In order to cover it up he hit the wall gently with his forearm, making sure not to use so much force that he’d crack the plaster. Focusing all his thoughts on the exact amount of pressure necessary, he managed to block out all his other thoughts, at least for one blessed moment. But then they all flooded back, compressed into one short sentence: ‘He’s not even French!’

But then he struggled to be fair. He was thinking that Ahmed wasn’t good enough for his daughter. But he hadn’t even met the man. He willed himself to retract his feelings about Africa. If European civilization meant anything, it meant the rule of law, the justice of the courts, telling your story before a judge.

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

Because her father was a general in the French Army, Anaïs believed that he was bound to appreciate the political and geographical aspects of Ahmed’s story. Her father was always saying that young people don’t know anything. She was determined to prove him wrong. Perhaps she could even make him appreciate the poetic subtlety of Ahmed’s situation as the Other, although she doubted it. Her father was about as sensitive as an accounting ledger.

Turning to him she said, “Why can’t you think with your heart for once? All you care about is the French Army and repressing other peoples’ freedom.”

Her father wondered if the children would really remember their parents, or would it just be a quick funeral, a long talk with lawyers, and then drunken reunions where they’d rehash all the things the parents had done wrong?

Still, she would help him to change. To this end, she reached into her pocket and pulled out two crumpled pieces of paper.

“Ahmed has developed a theory about the archetypal river of human origins. Even though he’s Algerian, he identifies with the American poet Langston Hughes, who also came from Africa. Only Africans understand what it’s like to suffer.”

Her father thought about those terrible family murders, the shame-killings that were rife in South Asia and the Middle East. Luckily God didn’t give him any commandments of the sort.

“Ahmed can quote the entire poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers in the original English. He speaks so many languages — Arabic, English, Spanish, Russian, Farsi. Of course he was forced to learn French.”

Did anyone ever ask what the children had put their parents through?

Anaïs lifted one of the pieces of crumpled paper and read:

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

“After reading the poem to me yesterday, he recited again, and again by heart, several lines from La Nuit Je Mens:

“He then picked up a copy of Les Miserables and read the first stanza of a poem he’d hidden, unbeknownst to Victor Hugo, between the bread crumbs and the policeman.” Anaïs read the second crumpled piece of paper to her father:

Ahmed’s Beard: A Hydrological Roots Saga

My beard grew along the waters of the Ganges, the water flowing from Mount Kailasa to the Bay of Bengal.

I saw the goddess Ganga, flowing through the dark strands of Shiva’s hair.

She sailed past Farrukhabad and Prayaganj, to the Sea of Dreams.

There was a part of Ahmed’s performance that Anaïs left out. After reciting the poem about his beard, Ahmed looked up from his copy of Les Miserables, and said in the voice of a Disney villain: “Of course, the Hindu gods — the licentious Hindu gods — are only metaphors.” His eyes glazed over, yet they remained fixed on the frayed wallpaper of the apartment. Shaking his fist at the paisley design, he said, “We will grind them to dust! We will crush their bones and mix them with our salt! We will throw the salt on the road for our camels to lick!

“We will descend again from the North, the scimitared cavalry of the mujahideen, and rip with our bare hands the stones of Rama’s temple in Ayodhya. Then, once the infidel bodies are impaled on the resurrected stones of the Babri Mosque, Prayagranj will become Allahabad once again!”

Anaïs was sure he intended this as a joke, or perhaps a mockery of the Hollywood versions of the Muslim villain. Yet his eyes looked strange, steely, as if he was repeating something that was both wrong and right. As if there was no distinction between the Hindus and their politicians. But then his eyes softened, and he said in a lighter tone, “In any case, I love their water imagery. Perhaps it’s better to say,” and here his voice became deep and sonorous again, as he read the second stanza — which Anaïs now read to her father:

My beard swept down the Jordan River, past Jericho to the Dead Sea. In the distance lay the Gulf of Aqaba and the Living Sea, tinted red by the henna of the Lord.

I heard the singing of the wadi herons when Muhammad went down to Mecca, and I’ve seen the black stone of the Ka’aba turn all golden in the dusk.

Anaïs hoped that her father would appreciate the ecumenical reference to the Jordan River and Jericho, given that his mother had made her own difficult journey from the Jewish ghetto in Kraków to the Parisian suburb of Sarcelles.

Anaïs asked her father, “Did you know that the Hebrew language descended on the Tigris and the Euphrates, from the Akkad of Sargon to the Arabs and the Palestinians, the Canaanites and the Jews? Ahmed says, ‘We must remember that we’re one Abrahamic family, one People of the Book. After all, Hammurabi was the first rabbi, and Muhammad was the final prophet of the Jewish line’.”

Her father was determined to judge the case impartially. He turned to the defendant’s lawyer, who objected, ‘It was just a poem about rivers! It was just a pun on rabbi!’ He then turned to the prosecutor, who observed that Plato had wisely expelled poets from his Republic. Puns were just another form of lie.

Her father thought to himself, Who knows what sort of damage was being done by the woke garbage they taught these days, and by the hip-hop music they listened to? To them, every Black sound is a magic bell, whether it’s African or American. But then again, the Algerian quoted “La Nuit Je Mens,” so he must know something about being French.

Who doesn’t have a mountain of questions in their boots? Her father thought of his own father, and wondered if he would ever meet him again. “At night I lie, I take a train across the plains… Where is your echo now? Where is your echo now?”

So he couldn’t really be the judge. He would have to meet the man first. All he had was a tight fist planted against a plaster wall. The judge was somewhere else, raising his gavel. But he refused to bring it down.

Anaïs ended her paean to Ahmed’s beard by telling her father that it was dark as ebony, from his lower jaw down to his belly button. From there it continued, the difference in colour and texture almost imperceptible, into the dark jungle of his pubic hair. His glorious beard was like a black and glistening prayer mat for the centre of his soul, his Muslim heart.

Her father knew that if he raised his voice or issued commands, Anaïs would double down, throw a tantrum, and not talk to him for days. He therefore suppressed any form of expression as she continued her account of Ahmed’s family — of his uncle who was a school teacher in the madrasa he opened in Sarcelles, and of his mother and two sisters who never went out after 8 PM and who apparently filled their small Belleville apartment with the exotic warble of Arabic day and night.

She reminded her father that Hebrew was a Semitic language, just like Arabic.

He relaxed his fist and let his arm fall back to his side. She was 17 years old, and he remembered what that meant. At that age he had told his father — a poet in the Latin Quarter who turned their home into a barricade against The System — that he had joined the Army.

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

Anaïs also told her father about Ahmed’s mother and her long pointed shoes. Made of tough Maghreb leather, their green stars and arabesques made Anaïs think of magic carpets and rides on Aladdin’s Roc. Ahmed’s mother was such a lovely woman, although she hardly ever said a word. And yet the stony glint of her eyes spoke volumes from beneath the fine filigree mesh.

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

Unlike Ahmed’s mother, Anaïs was a voluble young woman who never passed up an occasion to say what was on her mind. In this way she was more like Ahmed’s sisters, although their upbringings couldn’t have been more different. While they went to the Muslim school in Aubervilliers, in the northern outskirts of Seine-Saint-Denis, Anaïs had spent her 17 years in the posh Frenchness of the 8th arrondissement. She went to a private international school, and mixed with the sons and daughters of executives and diplomats from every corner of the earth.

Anaïs said that it was this international school that made her a world citizen. To the dismay of her elegant mother, Anaïs said that it was because of their decision to send her to this school — instead of the local lycée where all her friends went — that she mixed so easily with Arab and Iranian boys who wanted to join ISIS to get back at their parents, with American girls who were girls one week and boys the next, with American boys who were boys one week and girls the next, and with Mexican and Colombian boys who would never become girls and who would one day inherit vast empires that had nothing to do with pharmaceutical companies registered on the stock exchanges in Mexico City and New York.

Her mother desperately tried to change the conversation — hoping to tell Anaïs about the Gaultier dress she saw that morning in a shop. The dress was a bit risquée, but at least it would cover her underwear — but Anaïs was carried away by her new global consciousness: “I feel more comfortable with Mahgrebi and Saudi boys than with the French princes of the polo club. They shave the few hairs on their chins and put on fruity perfume, like sissies. At least Arab boys dress and smell like men. Mom, do you know what oud smells like? It’s a heavy, masculine cologne the Arab men use. When you smell it, you feel like you’re coming from the desert into the wadi, with its smell of spices and cedar-wood fires.”

Her mother didn’t know what to make of being lectured about perfume, but she couldn’t help pointing out that Anaïs’ dress-code must differ drastically from that of Ahmed’s sisters: “I doubt they wear thongs, at least not thongs that you can see. You don’t have la moindre idée how to dress comme il faut, either in this country or in theirs!”

Anaïs retorted, “This is their country. I’m a free spirit and won’t be bound by anyone, least of all my parents. I’m a sartorial ambassador of the world, more than capable of bridging the cultural divide between nations — not to mention the meaningless divide between the haute couture of the 8th arrondissement and the slutty exhibitionism of the 9th!”

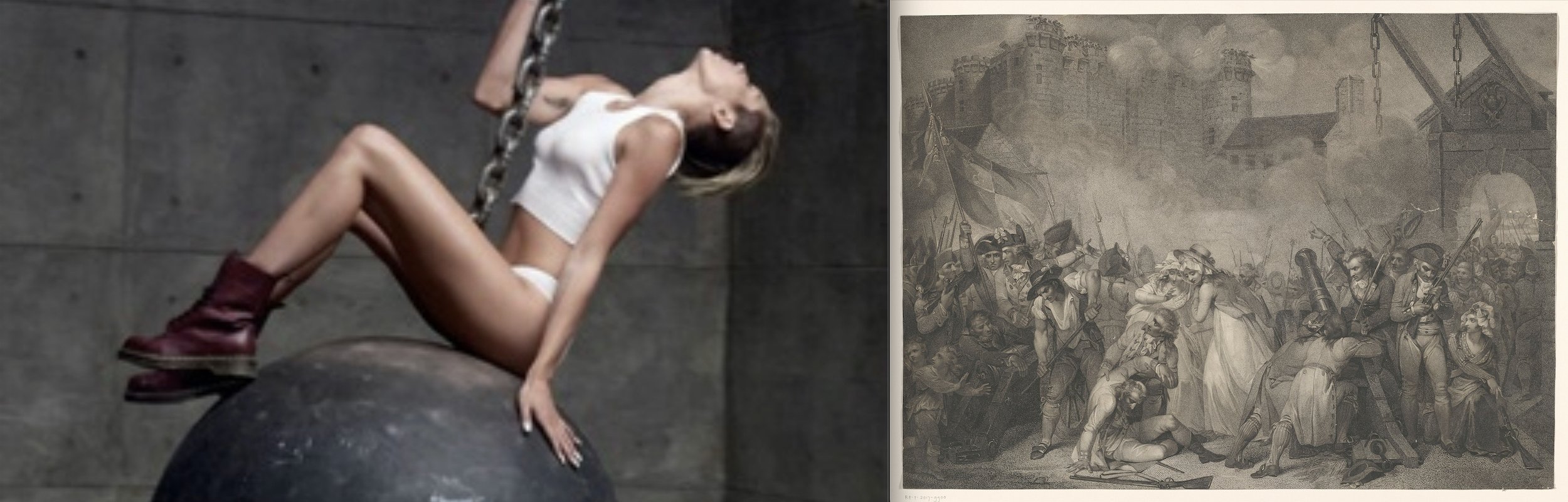

She opened her laptop and played a video her American friends showed her years ago: Miley Cyrus swinging on a wrecking ball.

She told her mother, “The iron ball she rides between her naked legs is the will of the people. The stone wall toward which it swings is the Bastille of elite privilege.”

“The Blanche tarts with their frayed panties have been discriminated against long enough. It’s high time French society validated their see-through world! Vive la transparence! Remember, through tattered clothes small vices do appear; robes and furred gowns hide all.”

Her mother was at pains to connect the Shakespeare quote to the argument. Perhaps Anaïs was suggesting that the tatters of the destitute should remind us of their plight. And yet Anaïs was anything but destitute! King Lear was raging against the loss of shelter and power, not making an argument about putting body parts on display. Why couldn’t she learn from the mistakes of Cordelia and do what her father wanted?

It was like Alfred said: they didn’t teach them anything in school these days.

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

Her parents tried everything to get Anaïs to dress and behave like a proper lady. Her mother took her to the finest shops on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, yet Anaïs insisted on buying skanky outfits in the Goutte d’Or. She left pamphlets on the breakfast table for riding lessons, with handsome rich young white French men holding the reins. Yet all Anaïs could talk about was see-through clothing and the silver bangles on Ahmed’s powerful wrists with their thick dark hair.

Alfred even bought a candy-red baby-grand in the hope of enticing Anaïs into playing the piano. They begged her to come with them to classical music concerts (they had a box for her and her boyfriend, who they’d never seen) and to Molière plays at the Comédie Française.

Determined to resist their cultural imperialism, Anaïs slammed her bedroom door and turned up Megadeath on her small but very powerful speakers.

Once she was free from their harassment and out on the streets, she played Beyoncé on her earpods.

As she walked up Rue Saint-Lazare she imagined herself swinging a bat at the fancy cars, all the while making eyes at the French boys with their ebikes and their unfiltered cigarettes. The boys winked at each other, as if to say that she was indeed the tightest little minx they’d seen from Bois de Boulogne to Père Lachaise.

Anaïs also winked at the Arab boys. She felt it was her duty to educate their mothers, to demonstrate that it was OK to expose your waist and to wear lingerie under a torn leather jacket slung over your shoulder. Along Boulevard de Belleville she got a thrill walking past the mosques and bazaars showing her nipples in public, under a sheer bra that she told Ahmed’s sisters was the latest fashion. She also gave them a copy of a poem she wrote, called “The See-Through Burkini.”

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

Because cultural exchange was a two-way street, she finally brought Ahmed home for dinner.

After he took off his shoes in the vestibule, she reassured him that it was OK to pray for as long as he wanted before dinner. He could lay his Karbala prayer mat (which he brought with him everywhere) over the British India rug in their living room, beneath the portrait of Louis XIV and General de Gaulle.

She told him that he should feel free to her parents informally, using their first names and tu, just to be friendly. He should also defer to her father and ignore the existence of her mother, just to be respectful.

She encouraged him to talk to her father after dinner about Rumi and Hafiz, and about the way Al-Ghazali saved the Muslim world from the cold rationality of Eurocentric philosophy. She told him that her father valued debate, and that he would welcome Ahmed’s frank evaluation of French terrorism in Africa.

🇩🇿 🇫🇷

There was nothing Anaïs loved more than to drive her parents mad.

🇩🇿 🇫🇷