Gospel & Universe 🎚 The Priest’s Dilemma

Rivers of God

Seine & Saraswati

In his little room one block from the Seine

Jean-Luc kneels in front of a small altar to the Mother of God.

He recites the ancient, inevitable words,

not the newfangled German tacked up on a door

somewhere in Saxony along the Elbe,

and certainly not the English slogans

so fashionable now on the bursting t-shirts

of the dancing Madonnas and Our Lady of the Gaga dolls.

No, his words go back to the Latin and Greek,

the Hebrew scriptures, the Aramaic script,

and the Phoenician that gave it birth.

Yet even that, he feared, was not the beginning.

Before Phoenician was Akkadian,

and before Rome and Jerusalem were Thebes and Uruk.

Before culture flowed onto the banks of the Tiber and the Jordan

were the Nile, the Euphrates, and the Saraswati.

L'Écriture Sainte

At times Jean-Luc grew tired of the promise of Vatican II. In his small room in Maison Saint Augustin he looked up at the gigantic photograph of Jean-Paul II, who had been canonized several years ago, on April 27, 2014. Jean-Luc loved the man, but he also wondered how the frame got so big.

Next to it was a large photo of the new Francis, not yet transformed into a saint. Jean-Luc wondered how he suddenly contracted all those super powers. He was once simply Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Mario. Jean-Luc imagined him with his bright red hat, interdicting fireballs, ascending to the heavens, and hurtling bright green turtle shells from his popemobile.

Jokingly, he said a few God the father of mercies to forgive himself for his indiscretion. Yet, in all seriousness, what was there to forgive? Was the pope really so far above us? Was this what Jesus taught?

Jean-Luc thought about Francis' notion that the Church be open to everyone. The problem was, some people assumed that what he meant by everyone included everyone — including women and homosexuals. But Francis then added that this use of everyone didn't change the fact that women could never become priests and that marriage was only between a man and a woman.

If the Mother of God showed up at the seminary gates, she would be turned away, while men of harrowing faults were ushered up the steps and into the hallowed spaces of the apse.

Jean-Luc shuddered to think of the recent scandals in Boston, and of the mothers who sat in the front row while the priests intoned the sacred vows. These men who called themselves priests then proceeded, in the vestiary, to bring down the altar boys.

Why pretend to change and to love, when you won't even change for love? His face flushed with embarrassment just thinking about it.

His frustration with the slow pace of Vatican II led him out of his cell and into the streets of the Latin Quarter. His disillusionment led him westward, up the steps of the Collège de France, and into the lecture halls where gay men and lesbians were permitted to climb the steps to the podium. Hindus, atheists, Mormons, anyone could speak who had something to say.

In the secular space of this unhallowed apse, they discussed things that the priests left out — things like universal rights, recent astronomy, sexuality, secularism, DNA, the right to die, the conundrum of biblical scholarship, evolution, and the 150 year-old deciphering of cuneiform.

Together with the Sorbonne, the Collège de France had some of the world's leading experts in Assyriology, the study of the civilizations that used cuneiform. Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria.

Cuneiform itself fascinated him. It was a seemingly simple, 5000 year-old script named after wedge-shaped marks pressed into moist tablets of clay.

Jean-Luc imagined the fingers of God pressing into the clay. Into the water and the dust. Moistened by the baptismal waters of the earliest rivers known to man. He thought of Langston Hughes' poem, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers":

I've known rivers:

I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I've seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I've known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

La Géographie

The Church was obsessed with Hebrew geography. Yet what did it matter if Jean-Luc read the old stories by the River Jordan or by the banks of the Nile? By the Ganges' side or by the rivers of Babylon? Why were any of them more sacred than the Seine?

The Church was obsessed with the letter J. Jericho, Job, Joshua, Jesus, Jacob, Joseph. Jeremiah and John of Patmos. The River Jordan. The Jews. Everything had to come from that particular tribe, that particular land, their particular book. Yet what did it matter if Jean-Luc read the old stories in the Bible — God formed man of the dust of the ground — or if he read them in the Epic of Gilgamesh — The Goddess pinched off a piece of clay and threw it into the wilds. She then fashioned a primitive man, Enkidu, the offspring of silence and lightning. What did it matter if the Hebrew Noah built the ark — Make rooms in the ark, and cover it inside and out with pitch. [...] The length of the ark shall be three hundred cubits... — or if it was the Mesopotamian Utnapishtim — The children brought pitch ... each side of the deck measuring one hundred and twenty cubits... .

In one story Yahweh wanted to drown the world, but then he warned Noah. In another, Enlil wanted to drown the world, but then Ea warned Utnapishtim to build an ark. What did it matter who said what to who, as long as the Heavens relented?

What did it matter who was tested, Job or Gilgamesh, as long as at some point there was redemption? The one thing Jean-Luc held onto was that at some point cataclysm turned into salvation. At some point, water turned into wine. Long after the blood of the Sumerians mixed with that of the Akkadians, long after Abraham left the city of Ur. At some point, through the Egyptians or through existential despair, the flooding ceased, and the water turned to wine.

Jean-Luc held onto this hope like a wooden cross swept sideways in a flash-flood crashing through the Zagros foothills. He imagined that he was a friend of Noah's, but Noah hadn't mentioned anything about the weather. Or that he was a friend of Utnapishtim's, what did it matter?

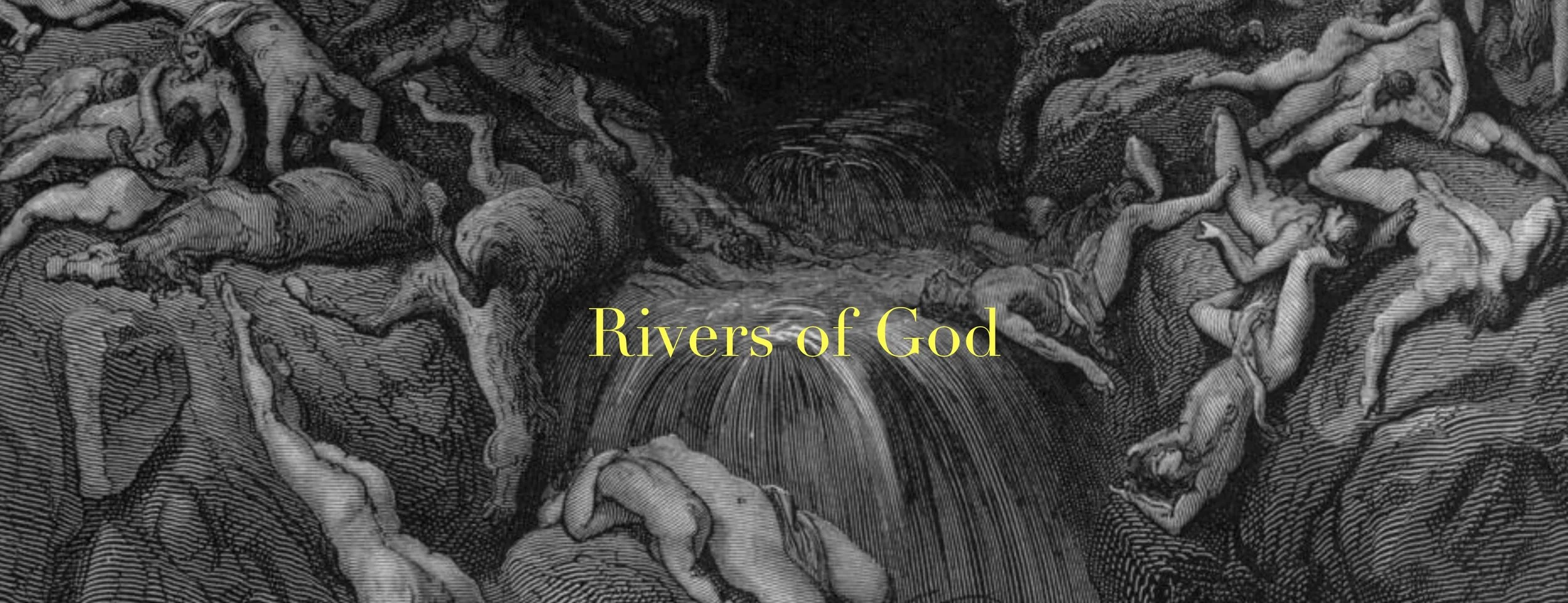

A Dove Is Sent Forth from the Ark (Gen. 8:1-13), from Doré's English Bible (1866), by Gustave Doré. From Wikimedia Commons.

Jean-Luc felt the currents of the Ancient World every time he imagined himself lifting the chalice and every time he imagined himself placing the wafer on a tongue. He thought of the waters of the Euphrates — or the Jordan or the Nile or the Seine, what did it matter? — mixing with the wheat. The wheat that was the body, and the water that was the blood. The blood that was wine.

Yet the Church refused to acknowledge the deep currents of those other rivers. Instead, it peopled their banks with blasphemers and worshippers of false idols. Then it pretended that the old stories came from the thin air of the desert. That one people, and only one people, journeyed from the desert to the well. According to all the popes, from Saint Peter to Jorge Mario Bergolio, only one group of believers, believing one version of history, could drink the water that was wine.