The Double Refuge ♒️ The Currents of Sumer

The Bounty of Sumer & Akkad

An Immediate Strangeness - A Strange Familiarity - Reformations

♒️

Bringing in Babylon as a vibrant and creative civilization, rather than as a sub-standard culture and wicked enemy of Israel, allows us to see the biblical texts in a light that is at once strange and strangely familiar.

♒️

An Immediate Strangeness

We can’t ignore the fact that the Mesopotamian texts seem strange to us. I would argue that this is because of at least two reasons: 1. Judaeo-Christian tradition makes it seem like Mesopotamians inhabited a strange, uncivilized, polytheistic culture, and 2. there was a 2,000 year gap during which we couldn’t read cuneiform. During this 2,000 years writings such as Gilgamesh were a hidden rather than a visible foundation to the culture and religion of the Near East. Ideas such as a Creation from watery Chaos, a Flood caused by a high god, an ark of so many cubits, a bad serpent, a boat that ferries us across the river of death, are familiar now, but the originals of these ideas aren’t familiar. They were never traced, never consciously or unconsciously integrated by the Jews, Persians, Greeks, Romans, French, or English. When Gilgamesh resurfaced in London in 1872, it naturally seemed more strange to us than the more recent narratives from Persia, India, Greece, or Rome.

For 2,000 years in the biblical account Noah appears to be an original character. Perhaps this is because 1. Hebrew writers assumed people would see the link to earlier stories, 2. Hebrew writers intentionally didn’t refer to earlier stories, and/or 3. the earlier stories were written in cuneiform and very few people could read cuneiform by the middle of the first millennium BC. In any case, by the Christian era, reading cuneiform was a thing of the forgotten past.

♒️

A Strange Familiarity

And yet, despite this apparent cuneiform oblivion, something strikes me about the Biblical timeline. The common understanding is that when you add up all the numbers in the Bible, the world began in 4004 BC. What started then? Civilization. Where? Mesopotamia.

Uruk, from Wikipedia

The Uruk period (c. 4000 to 3100 BC) […] Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization. The late Uruk period (34th to 32nd centuries) saw the gradual emergence of the cuneiform script …

I don’t cling to this possibility, yet if one looks at Gilgamesh in light of its popularity in its own time, and in light of the masterpieces of literature, its influence seems more and more likely. Here’s the opening paragraph from the introduction to Gilgamesh in The Longman Anthology of World Literature:

The greatest literary composition of ancient Mesopotamia, The Epic of Gilgamesh, can rightly be called the first true work of world literature. It began to circulate widely around the ancient Near East as early as 1000 B.C.E., and it was translated into several of the region's languages. Tablets bearing portions of the epic have been found not only around Mesopotamia but also in Turkey and in Palestine. We know of no other work that crossed so many borders so early, as people in many areas began to respond to the epic's searching exploration of the meaning of culture in the face of death.

Gilgamesh and the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible) are both epic works of literature. While one can attempt to minimize the importance of the former for partisan theological purposes (to increase the importance of Judaism and Christianity), why not see them both as powerful currents that lead out from the dim past to enliven the cultural flow of the world? Here’s the final paragraph from the Longman introduction:

First recorded a thousand years before either the Greeks or the Hebrews learned how to write, Gilgamesh's story circulated through the Near East and Asia Minor during the centuries in which both the legends of Genesis and the Homeric epics were developed and eventually written down. Both the Eden story and the Flood story have clear parallels in Gilgamesh, whose restless hero can also be well compared to Odysseus, even as his fated friendship with Enkidu can be related to the relationship of Achilles and his beloved friend Patroklos. Gilgamesh's story continued to live on in his own region in oral form, and his adventures have echoes in The Thousand and One Nights in such figures as Sindbad. Now that the epic itself has at last been recovered, its haunting images, its moving dialogues, and its engrossing drama make it once again, after two thousand years of oblivion, compelling reading today.

Reading the Bible in light of Mesopotamian religion and in light of the epic of Gilgamesh — whose origins appear to lie in late 3rd millennium BC poems about a legendary Sumerian king — can enrich our understanding of both the Bible and the Ancient World. It can also create what I would call an appreciation of the double strangeness, by which I mean the positive shift of our sense of strangeness into a new and perhaps even stranger sense of recognition. First, we’re confronted with strange gods, like Marduk and Enlil, and strange names like Utnapishtim. This shock is then doubled, twisting itself into an even stranger recognition, when we see ♒️ Marduk rising from the polytheistic pantheon to become a monotheistic God like the ill-fated Aten, or like the more successful Yahweh. For like the God of the Israelites, Marduk ♒️ faces the deep abyss and ♒️ gives order to the universe.

I’ll illustrate this paradox of strangeness with a few parallels that seem striking to me. I’ll mark the items on my short list with a water sign, in an attempt to underscore the notion that these are all brooks, streams, rivers, estuaries or undertows of the currents of Sumer.

♒️ Creation in the Bible is very similar to Mesopotamian narratives, as Enn and Botteró recognize.

♒️ In the Bible, two of the rivers running from the Garden of Eden are the Tigris and the Euphrates (in Greek, Mesopotamia means between rivers, or by extension between the Tigris & Euphrates).

♒️ The snake causes Adam and Eve to be expelled from the heavenly Garden; a snake steals the herb of immortality from Gilgamesh.

♒️ The stern high god Enlil acts like Yahweh when he drowns humans in an apocalyptic Flood. ♒️ The only humans who survive are Utnapishtim and his wife, who ♒️ build an ark, ♒️ send out a bird, ♒️ perform a sacrifice, etc. On a previous page, The Flood, I point out the strikingly similar details of the two narratives, as well as some of the biblical implications when we see Utnapishtim as the blueprint for Noah, a Jewish figure who appears much later in the annals of history, archeology, and philology.

♒️ The first patriarch, Abraham, comes from the Mesopotamian city of Ur, which started around 3800 BC. (Gilgamesh is the king of the even earlier city of Uruk).

♒️ The Bible supplies a story about man’s original sin. This may help to explain the bizarre situation in Gilgamesh, where one man (Utnapishtim) and his wife get to live eternally while everyone else is consigned to a dusty and grim afterlife — which I call the half-life that constitutes the afterlife for the early Hebrews and Greeks.

♒️

Reformations

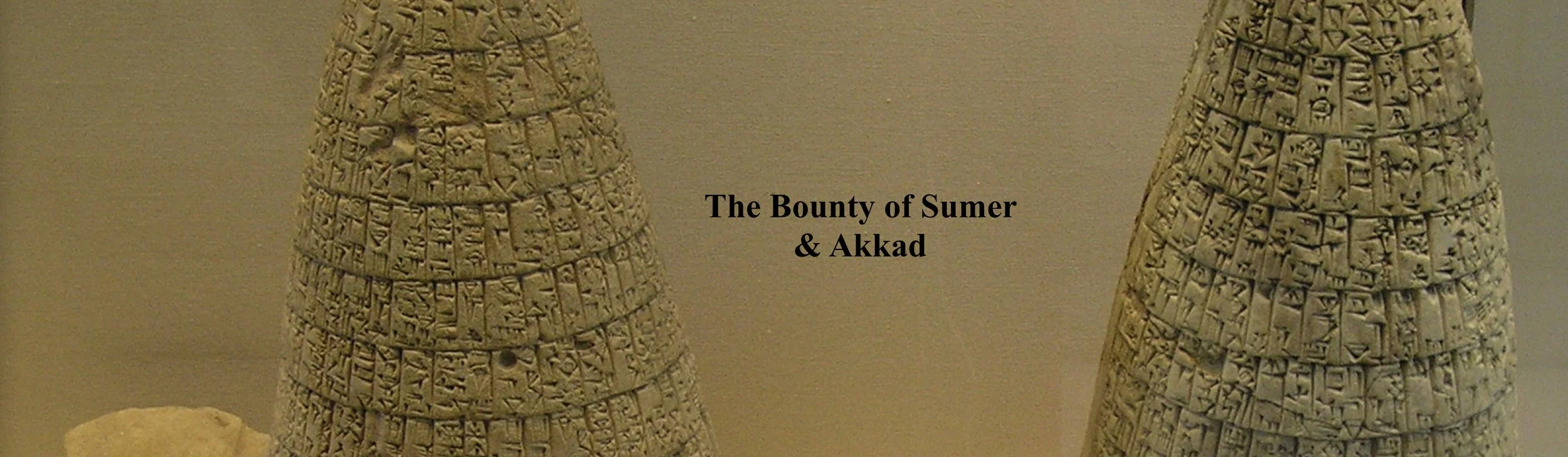

Although I’ve been emphasizing the mythic and religious aspects of Sumer and Akkad, I’d like to end this page with a four and a half thousand year old cone that highlights the importance of secularism and real-world politics.

Below is a photo which I took in the Louvre, and which I used for my title graphic at the top of this page. In the description below the photo, one can see that our secular and humanitarian concerns were also an issue in 2350 BC in the city of Lagash.

Translation: Cone of Urunimgina, relating to the reforms of this prince against the abuse of the ‘old days’ - Baked clay, Tello, c. 2350 BC

This Sumerian document, as well as two other similar cones, comes from the Archives of Uruinimgina, the new man who was put into power by the people after the end of the Ur-Nanshe Dynasty. From his accession, he undertook a policy of reforms with the aim of restauring the old order, which had been compromised by the abuses of the rich and powerful, principally the palace and the temples. The character and the scope of these reforms perhaps have an anti-clerical character, but they also show a desire to ease the suffering of the oppressed. They aimed at a reduction of taxes levied by the priests. They respected the goods of the temple, and “from one end of the country to the other … there were no more taxmen.” Uruinimgina, had “given freedom” to the citizens of Lagash. He also rid the city of usurers, thieves, and criminals: “If the son of a poor man managed to find a pool to go fishing, no one would now steal his fish.” These reforms didn’t succeed in giving him back his power in Lagash. Uruinimgina was defeated by Lugalzagesi, king of Umma, his old rival, and Lagash would never recover.

Some things never change.

Next: Friendly Gods