Collected Works ✏️ Vancouver

The Subterranean Homework Blues

7:55 AM

Dr. Rexroth is staring down at me with his usual intensity. Although his lips are pressed tight, I distinctly hear him say, “Don’t mess it up this time, Matthew.” He drops the exam instructions, front facing downward, on my desk. The piece of paper is violet, unlike the white sheets dropped onto the desks by the professors of Sociology and History.

7:59 AM

Exam instructions are now on every desk of the Osbourne Gymnasium, which is the proud home of the UBC Thunderbird teams, whose banners deck the walls and float from the rafters. According to their website, on October 30, 1948 the Kwicksutaineuk people “officially grant[ed] permission to UBC to use the Thunderbird name and emblem.”

The clock is about to strike the hour. Thunderbird pennants flutter in the wind of the air-conditioner above. The ghosts of the Thunderbird elders are watching, with eagle eyes. They’ve seen what the old White people have done to the forests, the rivers, and the fish in the sea. It’s late in the summer, and they’re anxious to hear what the young White people have to say about it.

The Doctors of Philosophy exchange wry glances from their makeshift tables at the front of the gym. Meanwhile, the students recite The Lord’s Prayer in every language from Tagalog to Greek: Yea, though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death…

The clock strikes the hour, and the students turn the page.

8:00 AM

The exam paper lies before me, like a siren mocking Odysseus. Old Rex even went to the trouble of printing the exam on coloured paper. Hellish shades of violet. A warning about the journey ahead.

The Inquisitors are making their rounds of the gymnasium, like priests in Blake’s Garden of Love:

And I saw it was filled with graves, / And tomb-stones where flowers should be: / And Priests in black gowns, were walking their rounds.

I must remember everything. Otherwise the Grand Inquisitor, who knows everything, will assume that I know nothing.

2:00 Am the night before

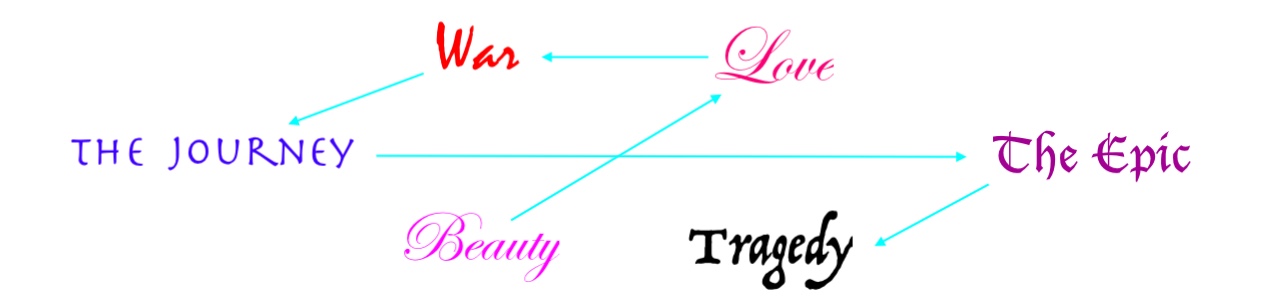

Six hours to go until the exam. I consult the prep sheet. Six possible topics to write on: Tragedy, The Epic, Beauty, The Journey, Love, and War. Old Rex added the following instructions: “You will write your essay on one of the six topics. The day of the exam, I will roll a die and Fate will determine the precise manner in which your number is up. The die will decide. There’s no point trying to second-guess my intentions.” To underscore his point about Fate, he included a colour print by Walter Crane:

Six hours to go. Six topics to choose from. Six paths into the dark woods. 6 X 6 X 6. If that isn't ominous, what is?

About a month ago I figured that I didn’t have to come up with an argument, so much as a counter-argument to the main point he hammered home all year — that the Western Epic is the greatest thing on Planet Earth. Coming up with a counter-argument was easy enough, since I disagreed with almost everything Old Rex said. So, I decided that in the exam I could repeat Old Rex’ argument, occasionally questioning it and suggesting alternative interpretations. I knew this was a dangerous strategy, but I could preface my essay with the quote from William Blake: “Opposition is true friendship.” If there was one thing Old Rex needed, it was a friend.

In the exam I could use the same line of reasoning, the same combination of all six topics, no matter what specific topic the old goat rolled. I just needed to expand on the one topic he rolled, and build reminders of that topic into my general discussion of what he had been talking about all year.

I fit the six topics within a cause-and-effect structure: Love & Beauty causes War & The Journey, which causes The Epic & Tragedy.

I could preface my Aristotelian cause-and-effect argument with the following quote from Hamlet’s councillor Polonius:

That we find out the cause of this effect, Or, rather say, the cause of this defect, For this effect defective comes by cause.

Polonius is in fact a pompous ass, yet the quote will serve two functions: 1. it will unnerve Doctor Fate, who is also a pompous ass, and 2. it will introduce my general point: far from being a sane and logical endeavour, the history of the epic is as defective as humanity itself.

Contrary to what Old Rex taught, it’s not as if this defect is a recent thing. He can expound all he wants about the Garden of Eden and the Golden Age of Greece, yet from the very beginning the defect is clear in the symbol of an apple: in the Garden of Eden Eve offers Adam a bite of the apple of knowledge; and in Greece the goddess of strife throws the apple of discord into the Judgment of Paris. Paris then judges who is the fairest of them all, and chooses Aphrodite rather than Hera or Athena — because Aphrodite has promised him the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Troy.

The epic doesn’t teach us that beauty and love are transcendent values, but rather that they are deeply intertwined with war and tragedy. Human defect is there from the start, turning love and beauty into pageants and side deals, and finally exile and war, which sooner or later bury us in tragedy. In Eden, the serpent’s apple causes the desecration of naked purity and beauty, underscored by banishment from Paradise. In Greece, Helen’s “face that launched a thousand ships” leads to the murder of Iphigenia, whose father Agamemnon sacrifices her in order to ensure strong winds for his war ships in their journey to Troy. This sacrifice is bad enough in itself, but it also allows the slaughter of war to begin.

✏️

A week ago I went on a quest for a book that lay outside Old Rex’s curriculum yet could nevertheless be set astride the Iliad & Odyssey. I wanted to show him that I wasn’t just rearranging his ideas and trying to knock them down, but that I’d learned from his arguments and was ready to make an argument of my own. I finally found the right book: The Voluspá: From Snorri to Wagner. Old Rex said something about The Voluspá months ago, but disparagingly. Perfect.

Like the epics of Greece, Rome, Italy, and England, the Voluspá works for all six topics. First of all, it has beauty and love, the type that starts everything, from Creation to the Trojan War. This beauty isn’t the glory of the sunset, but the capitalized Beauty that leads to love and fornication. The type of beauty that spins the head of even the most lustful satyr:

The beauty that teased poor old Alberich out of his mind, and made the giants dream of a soft-skinned bride:

The beauty that made a jealous Greek husband launch a thousand ships, and caused Adam to eat of the forbidden fruit.

The Voluspá also has ❧ a cosmic battle, ❧ a journey of hell-bent demons in a boat, ❧ an epic form, and ❧ an apocalyptically tragic ending.

When I cracked the book open, the first thing I saw was The Battle of the Doomed Gods (1882) by Friedrich Heine:

The End of the World. While reading the Völuspá (also called The Prophecy of the Völva), I listened to Wagner's Twilight of the Gods, hoping that the spirits of Odin and Thor would descend upon me like a storm of warrior poets ready for battle.

8:15 AM

The gymnasium is almost silent. The only sound is that of students turning pages and clicking their pens. My eyes are weary yet caffeinated to the point of hallucination. The topic lies before me: The Epic, from Odysseus to J. Alfred Prufrock.

Did Old Rex really roll a die to arrive at that topic? I doubt it. I suspect that the game is rigged. Why? Because Old Rex is a control freak. And because he’s a Classical Greek scholar who’s in love with Lord Byron.

2:01 A.M.

I pour a bath to settle my nerves, and set up a makeshift work station around the furious tumbling water. The spine of the Völuspá lies on the faucet, and the open pages ride atop the hot and cold water taps. I turn the pages, slightly moistened by the turmoil below the falls. On the toilet seat is my trusty Mac Air: thirteen inches of screen and rubber keys connecting me to the chaos and harmony of the world.

I'm mesmerized by the apocalyptic language of the Völuspá. The rebel Loki, the wolf Fenris, and the giant snake Jörmungandr are making their assault on the Aesir gods. Together with the fire-giant Sutr, they’re about to tear down heaven, light it on fire, and sink everything into the sea.

But how to work this Norse myth into a coherent line of argument about the epic? I remember Old Rex referring briefly to the difference between the northern sagas and the southern epics: he said the Norse and German stories were crude and inferior, and they could never compete with the Greek and Roman epics. Yet as far as I can see, whether it’s in Valhalla or on Olympus, it’s all about in-fighting, lust, conniving, and war.

Old Rex is obsessed with the Greeks, their Golden Age, their law and order, their famed democracy, and, above all, their Iliad and Odyssey. And yet the Classical Greeks also fell into chaos and darkness: war with the Persians, the execution of Socrates, and then a fratricidal war with the Spartans.

Several nights ago I was worried Old Rex might pick the topic of war, so I watched Troy. I was moved by how sad Achilles and Priam are at the end, when they see the futility of it all. After all the lame reasons for battle and butchery, Peter O’Toole sneaks into the Greek tent and sits with Brad Pitt, the two lamenting as only enemies can. Achilles and Priam, having lost everything, for nothing.

If the Trojan War was the start of Western Civilization, it was a bad start. And it never really ends, does it? There’s no such thing as The war to end all wars, Mission Accomplished, or a special military operation. Maybe these Vikings, the ones we conveniently distance ourselves from and treat as violent figments of the Dark Ages, aren't so different after all. Maybe the battle of the gods — the dark vision of the völva, with its destruction of the world — is what we keep doing, despite our vaunted Classical Age, our Renaissance, our Enlightenment, and our liberal democratic End of History. And maybe the women, the wild rheinmaidens and the fateful valkyries, are our only hope.

Love creates war (Helen’s affair with Paris & Agamemnon’s revenge), and beauty turns to tragedy (Helen’s face launches a thousand warships, which bring about the collapse of peace, order, and civilization). The epic and the journey combine to carry these themes through, highlighting war (the battle for Troy in the Iliad) and love (the romantic adventures of Odysseus in the Odyssey).

I look down into the swirling water and see beauty and love fall into tragedy and war. I see the crowds swirling toward the beach. Promenade des Anglais. Nice. The beauty of the goddess Isis turned into a monster, mowing down infidels on the fourteenth of July. The Bataclan. Weapons of Mass Destruction. Vietnam and Iraq. Syria and the Congo. All those special military operations. Global Warming. Water shortages. Eight billion people and counting.

Why do we fixate on Greek versions of tragedy when we've got so many of our own? Instead of repeating Aristotle’s fall of a noble man, why don’t we look at civilization itself, as it seems so willing to fall, again and again? As Bob Dylan said in "Subterranean Homesick Blues," Look out kid / It's somethin' you did / God knows when / But you're doing it again.

The battle of the gods rises from confused currents and trembling stretches of calm.

This is going to be total collapse.

I look up from the swirling water. My laptop is firmly on the toilet seat. My notebook is trembling on my knees.

✏️

Next: ✏️ J. Alfred

Contents - Characters - Glossary: A-F∙G-Z - Maps - Storylines

![“An illustration by Willy Pogany from a chapter from Children of Odin [Colum, Padraic, 1920] entitled "The twilight of the gods […] Flames rise up to Asgard and the broken bridge of Bifröst during Ragnarök.” From Wikimedia Commons.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55c58254e4b0a9ad6b25bf97/1551293753500-0321IQCBJS4WM2H2DSLK/The_twilight_of_the_gods_by_Willy_Pogany.png)