The Double Refuge 🇮🇳 The Fiction of Doubt

Eruptions of the Sacred

Hierophanies - Poltheistic Polysymbolism - Hinduism & Daoism

🇮🇳

Hierophanies

In The Sacred and the Profane Mircea Eliade argues that a hierophany, an eruption of the sacred, “allows the world to be constituted, because it reveals the fixed point, the central axis for all future orientation” (21). In Rushdie’s early fiction, this kind of eruption provides a momentary orientation, yet it's often followed by darker and more chaotic eruptions. For instance, in Midnight's Children Saleem initially hears angelic voices but they turn into a cacophony of fallen angels, drunken djinns, and hundreds of diverse Indian personalities; in Shame Omar initially sees the screen of Qaf, but this is taken from his field of vision by his three witchy mothers, after which Omar ponders the heavens and the depths of the earth only to find intergalactic monsters and a frightening abyss; in the Verses Gibreel in his dreams hears the voice of Gabriel yet the reader can’t help but hear the voice of Satan, and the reader seems to be right as we see Gibreel wheel from one demented vision to the next. Often in Rushdie's early fiction, what begins as a liberating orientation, a meaningful vision of the universe, turns into a nightmare.

If Rushdie were strictly a magic realist writer, eruptions from some other world wouldn’t be as disruptive and problematic as they are. For magic doesn’t necessarily reverberate into the cosmos, doesn’t necessarily reach toward Shakespeare’s edge of doom, Yeats’ blood-dimmed tide, Dante’s ascension to the Heavens, or Attar’s blissful annihilation. When writers introduce a magical or inexplicable event into a framework of realism this doesn’t force them into an established system or cosmology. Yet myth does, and religion does with a vengeance. When writers introduce a religious symbol or motif this brings with it an entire cosmic system, a pre-fabricated universe dominated by figures such as Satan or Shiva and by ideas such as Apocalypse or Grace.

It may be that in order for writers to break free from conventional conceptions of the universe they can’t just ignore traditional models. If a writer creates a new cosmic realm detached from science or human history, or from established myth or religion, then the realm is a fantastic one. The particulars of such a realm don't necessarily have much to say about the belief systems that have shaped human thinking for millennia. Ancient otherworldly systems, on the other hand, orient the individual and constitute the world in a psychologically, culturally and historically responsive way. Often learnt in childhood, they have psychological impact even if the rational mind has rejected them. In terms of ontology and epistemology, they are well-rounded and can’t be dismissed easily or quickly, if at all.

In order to challenge an established cosmic system or orientation, it may be more effective to respond to it with an equally weighty or developed orientation. For instance, in questioning the notion of an afterlife in Paradise or Hell, the system called science is the most powerful counterweight, assuming the reader puts great store in rationality, cause and effect, verification, etc. If the reader puts store in theistic ideas, however, a plot involving reincarnation may be more effective. Even if one doesn’t believe in any particular version of the afterlife, there’s nevertheless a power structure based on usage, indoctrination and precedence. There’s a sort of “Common Law of the Unknown” which makes mythology and religion carry more weight than cosmologies which never gained adherents or which appear to be freshly hatched from the imagination.

Rushdie may not believe — or fully disbelieve — in the other worlds he includes in his early fiction, yet he knows that these have been employed for centuries and that they consequently reside and reverberate deep inside the minds of his readers. In The Study of Literature and Religion David Jasper observes that when people ask themselves fundamental questions, the language used is still steeped in cosmological settings and mythological figures:

The story of Eden and the figure of Satan remain alive in our emotions, and in the textuality of theodicy they continue to address the problem of suffering and evil in God’s world, however dead their ‘theory.’ (129)

Rushdie understands that ‘theory’ has been undermined by skepticism and other theories. Nevertheless, he brings it alive again and again by creating characters who believe in the otherworldly and by describing events which corroborate their belief. For instance, in Midnight’s Children Padma’s belief in witchcraft is validated when Parvati makes Saleem invisible. Even when characters such as Aadam Aziz, Omar, or Chamcha reject religion, they are indelibly marked by the very belief structures they reject.

🇮🇳

Poltheistic Polysymbolism

In his first five novels, Rushdie questions yet never entirely dismisses the notion that different epistemologies can be marshalled into a heterogeneous yet coherent view of the universe. These novels might be situated between what Lonnie Kliever calls monotheistic polysymbolism, which is associated with modernity and with the view that diverse systems contain universal meanings, and polytheistic polysymbolism, which rejects this universality. According to Kliever, polytheistic polysymbolism "celebrates the variousness and many-sidedness of all expressions of culture and religion. But it decidedly rejects the monotheistic ideal of a fundamental unity underlying and integrating this heterogeneity." This polytheistic polysymbolism is what some people find impossible to accept in Rushdie. His most ardent detractors are staunchly monotheistic and repeatedly blame him for promoting a fragmented vision of God’s universe. In addition, Rushdie's novels from Grimus to the Verses increasingly reflect the “historical dislocation,” the “apocalyptic pessimism,” and the “rising tide of occultism” which according to Kliever accompany the chaos of polytheistic polysymbolism (“Polysymbolism and Modern Religiosity” 178). Yet Rushdie’s fiction also suggests universal, idealistic, monotheistic perspectives. Idealistic or desperate, he returns again and again to Attar’s unity and annihilation, Shiva’s endless cycle of worlds, Somadeva’s Ocean, and other religious paradigms of infinite contextuality and creativity. Herein lies one of his fiction’s most challenging aspects, be it contradictory or paradoxical.

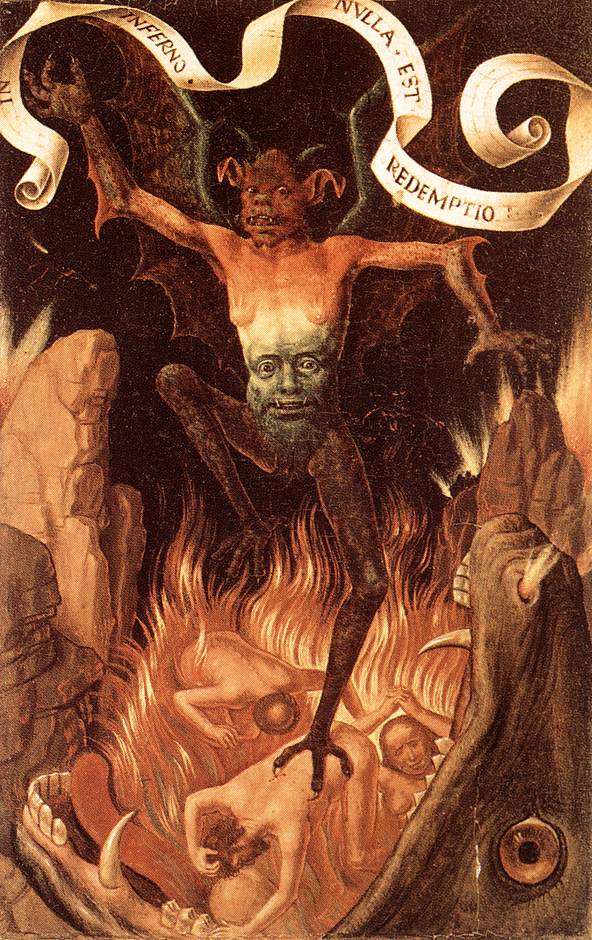

One of the problems in trying to weigh the fragmenting, pessimistic aspects against the unifying, optimistic aspects in Rushdie's early fiction is that each novel has a different mix of these. Grimus and Haroun are overt in their mystical optimism. Midnight’s Children and the Verses on the other hand suggest unity in an esoteric manner: the occult and the apocalyptic take on increasingly dire proportions. Shame is the darkest of Rushdie’s novels in this regard: the protagonist Omar is alienated from deep mystical perspectives (his three witchy mothers remove the screen of Qaf); he is also overwhelmed by the fearsome beasts of his nightmares (a horrific combination of Kali in her rage and the Devil in revenge mode). The ending of Shame brings to mind what Dante and Virgil see at the end of Inferno, where Satan uses his three mouths “like a grinder / [and] with gnashing teeth he tore to bits a sinner,” the sinner in this case being Omar. The important difference here is that Dante and Virgil move on to Purgatory and Paradise; readers can only shudder to think where Omar ends up.

🇮🇳

In “Religion and Literature in a Secular Age: The Critic’s Dilemma,” Theodore Ziolkowski argues that

the general secularization of Western culture has produced a new problem for literary interpretations because there is no longer a unified faith — what structuralists would call an epistemological field — that provides an automatic context of understanding for the literary work. (20)

Rushdie takes this dilemma to new heights, for he not only breaks open the Western treasure-horde of religious systems and epic narratives; he also adds a bewildering mix of Hindu and Islamic systems. The result could be appreciated in an eclectic manner, as a form of postmodern art. Yet for those who desire coherence, his fiction can seem like a global clash of polysymbolic hierophanies. In terms of coherence this is a disaster, yet in terms of metamorphic art it's a goldmine, leading to hybrids like the hell-bound Kali/Satan of Shame or the heaven-bound Simurg/Shiva of Grimus.

Goddess Kali dancing on Shiva, from Wellcome Images (Wikimedia Commons); Hell, 1485, by Hans Memling (Wikimedia Commons)

Simurgh on the portal of Nadir Divan-Beghi Madrasah, Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Source: Alaexis (Wikimedia Commons);Statue of Shiva at Murudeshwar, cropped from Big Huge Labs by Thejas Panarkandy (Wikimedia Commons)

Rushdie may disorient his readers with an alienating series of displacements, yet he also leads them on exciting explorations which hold out the possibility of a hidden orientation and an eclectic field of meanings. He disturbs those who would find solace in a coherent mystical system, yet he also suggests that multiple systems can have meanings of their own.

🇮🇳

Hinduism & Daoism

Parameswaran, Kanaganayakam, Aklujkar and Goonetilleke supply insight into Hindu aspects of Rushdie's work, yet no one (as far as I know) has yet published a detailed analysis of his oeuvre from a Hindu point of view. Throughout this study I suggest various ways in which Rushdie makes intriguing use of Hinduism, yet I don’t pretend to cover this angle in the detail it deserves. The Hindu tradition is of course vast. One might see Rushdie's cosmological speculations in light of the earliest Hindu scripture, Rg Veda, in which the poet says that only the being who lives in the highest heaven knows from whence this universe arises, “or perhaps he does not know” (Rg Veda 26). * Or one might see his fiction in light of recent writers, such as the tantric subversions of K.D. Katrak’s Underworld (1979) or the angst-ridden mystical conundrums of Arun Joshi’s The Last Labyrinth (1981). The Bhakti tradition might also provide insight into Rushdie’s mix of reference and rebellion, allusion and alienation, given that it works both with and against orthodoxy.

Wendy Donniger O’Flaherty’s study of Hindu myth might also supply insight into two key questions raised by Rushdie: What does it mean to exist in this or any world? and What does it mean to arrive at a confident reading of any story? Her comments on the Yogavasista are particularly helpful in appreciating Rushdie’s shifting and oneiric narrative structures:

If [the sage] Vasistha can plunge into the page and come face to face with the monk in his own story, as [the Vedic god] Rudra can go into his dream and wake up the people who are dreaming him, we cannot rest confident in our assumption that our level of the story is the final one.” (Dreams, Illusions and Other Realities, 244)

In her analysis of the story of Lavana and Gadhi, Donniger O'Flaherty asks,

Why could there not be a woman, say, dreaming that she was a king dreaming...? … In fact, this cannot happen in our text. For the Hindu, the chain stops with the Brahmin, the lynchpost of reality, the witness of the truth. To the extent that the Brahmin represents purity and renunciation, he is real, safely outside the maelstrom of samsara and illusion. Our confusion about our own place in the frames of memory, one contained within another like nesting Chinese boxes, is shared by Lavana until the very end of his tale. But to Gadhi, who is, after all, a Brahmin, the god who pulls the strings is directly manifest and takes pains to open his bag of tricks right from the start; moreover, he returns three times at the end to make sure that Gadhi has understood his lesson properly.” (Dreams, 138-139)

In Midnight’s Children, Shame and the Moor there’s no Brahmin or god who enlightens Saleem, Omar or the Moor about the meaning of their lives. In the Verses there’s no one even remotely similar to a holy man or deity who might inform Gibreel about the nature of the strange and dark journey he takes from one reality to the next. Instead, his strings are pulled without his knowledge by Chamcha, whose strings are in turn pulled without his knowledge by the satanic narrator (at least that's my reading of the text). While Grimus’ Eagle learns the meaning of his quest from three separate sources (Deggle, Virgil and then Grimus), the Verses’ Gibreel remains puzzled to the very end of his increasingly miserable existence. Gibreel’s universe isn’t like O’Flaherty’s mobius universe, whose final level is the transcendent continuum called God (Dreams, 244). Rather, it’s a downward, chaotic, splintering spiral whose final level is madness and suicide.

Taoism might also offer useful points of comparison. The third century B.C. writer Chuang Tze may be of particular interest, since he posits an ineffable Being yet refuses to pronounce on such things as the afterlife. Like Rushdie, Chuang Tze sees the self as an indeterminate entity which can’t possibly grasp the parameters of its own reality. In the Verses Rushdie appears to borrow from Chuang Tze, for Gibreel’s notion that he’s part of Gabriel’s dream echoes Chuang Tze’s parable in which a man wonders whether he previously dreamt he was a butterfly or whether he’s now a butterfly dreaming he’s a man.

Much of the meaning of Chuang Tze’s parable lies in the parable of the shadow which precedes it: the shadow can’t understand itself since the contours of its existence depend on the body which casts it. This body in turn depends on outside forces to do what it does, which in turn depend on outside forces to do what they do, ad infinitum (The Writings of Chuang Tze, 245). Rushdie’s fiction in general, and Gibreel’s predicament in particular, suggests that since the self is dependent on an infinite number of unknown factors, it can’t construct a coherent, encompassing framework or ideology.

It's tempting to read a postmodern or existential stance into Chuang Tze’s writing. Yet his understanding of displacement leads to a joyful acceptance of change and identity transformation, an acceptance which works in his philosophical system because he maintains a deep belief in the Tao or Way which guides and helps everything under Heaven. Rushdie, on the other hand, asks the disturbing question, What if there’s no such Way giving hidden meaning to the transformations of the self? In Midnight’s Children Saleem can only hope there’s a spiritual meaning in the annihilation of his Midnight’s Children’s. In Shame and the Verses the protagonists are unable to escape from an increasingly nightmarish universe. In Shame Omar ends up in the maw of the fearsome Beast he has dreaded since childhood, and in the Verses Gibreel dreams he is a tortured Archangel. Gibreel wonders if the Archangel is “the guy who’s awake and this is the bloody nightmare. His bloody dream: us” (SV 83). Rushdie pushes his readers even further into Gibreel’s dilemma by hinting that this Archangel is the Fallen Angel, and that Gibreel’s oneiric existence is a function of Satan’s perverted, violent imagination.

While the traditions of Hinduism and Taoism may help to get at the transformations and displacements in Rushdie's fiction, one must add to them the radical uncertainties of Modernism and Postmodernism.

🪐

Next: The Return of the Simurg