Seeing Double

🇨🇦🇫🇷

Location 1: Ice-blue winter skies; suburbs dotted with parks; names like Killarney and Eagle Ridge; playing hockey in a covered rink at six in the morning; bumper rides back from the rink over slick black and icy streets, the ruts of the car tracks like miniature ski jumps.

Location 2: Rain falling from a grey sky; block after block of six-story stone apartments; names like la Bastille and Montparnasse; crisscrossing the city, thirty feet below the surface on rubber wheels.

🇨🇦🇫🇷

My world began in two places. First, there was Calgary, with its foothills, its Stampede, and its inflated sense of power and destiny (oil can do this to people). And then there was Paris, where my father, who worked for the national French oil company, was transferred in 1975. I’d like to say that he, like the oil world he worked for, was tripping with power. It’d be convenient, rebellious as I am, to think that he was the archetypal tyrant. But the truth is that I was the terror, not him. By the time we got to Paris I had worn him down so completely that he let me do almost anything I wanted, even roam the brightly-lit morning streets, crazed with the idea that a fifteen-year-old could drink in almost any bar. This lack of strict parental control soon made me care more about my future, since it now seemed so precariously in my own hands. Parents can be crafty…

So I went from my comfortable little Calgarian world of sex, drugs, and rock and roll — perhaps best summed up by the evenings I spent with Marilou beneath the pool table in their basement — to a far different, far more perplexing world. It was a world where all those things on the news that I had previously ignored were the things that my new friends came from. For some reason, my parents thought it a good idea to send me to a bilingual school, even though I got kicked out of French class in grade eight for telling the teacher to go to hell. I was a real charmer…).

In Paris, there was a Chinese girl in my class who came fresh from ten years of insane and counterproductive Cultural Revolution (which I started calling the Anticultural Revolution). A Chilean friend came from a country recently upended: Allende was murdered two years ago, in 1973, in the dark days of Pinochet. A rich and very White South African friend almost turned red with guilt when our Geography teacher took us to a ratty community hall in Saint Denis. We saw a film on what it was like to be Black in her country.

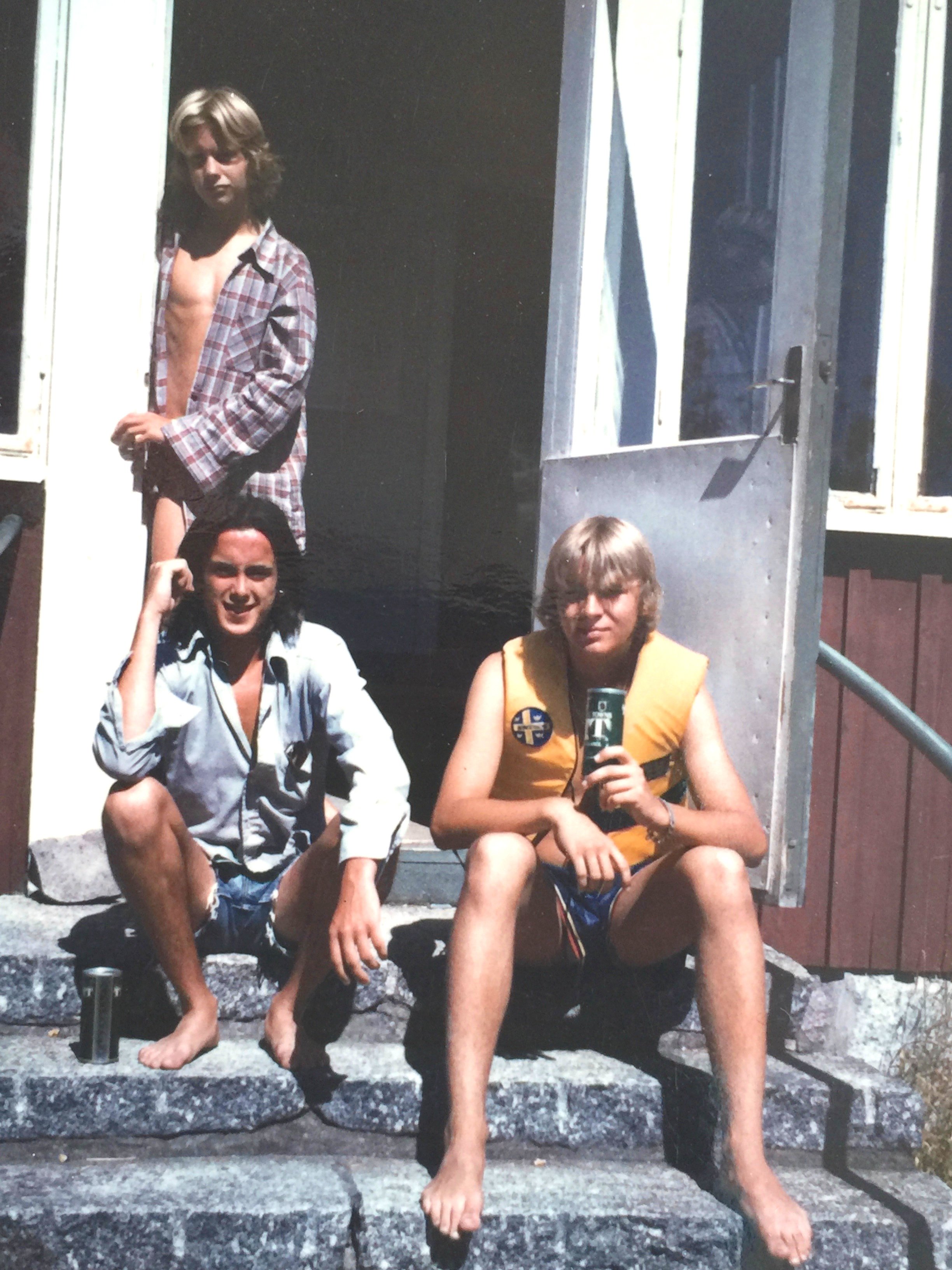

My best friend, from New Jersey, got me to listen to a guy called Bruce Springsteen. Jim lived life like a mad drunk Irish poet. I remember a sparring match we had in the kitchen of a fancy apartment — his boxing against my karate. He thought he was Rocky Marciano and I thought I was Bruce Lee. I’m still stubbornly proud to say that I gave him a bloody nose (You can take the boy out of Calgary…). In revenge, he tossed our Swedish friend gym bag into the street at 2 AM. Here we are the next summer, drinking beer and smoking pot in a cabin in Sweden:

I also remember a surreal evening with a Russian girl who left for Moscow the next day, leaving me with my disintegrating stereotypes and my James Bond fantasies. Ah, l’amour…

There were dozens of experiences I had that year that made it unique — as in this photo of my sister (standing), my younger brother (with the sombrero), my mom (sitting on the right), and several of the Bonafoux family we knew from Calgary (sitting in the middle), all having a strange little lunch party high in the Pyrenees…

In Paris I also encountered a visceral form of anti-Americanism. This at first seemed incomprehensible to me, coming from Calgary, which was in some ways a suburb of Houston. The only way anti-Americanism made sense to me back then was in protest songs against the war in Vietnam. It was 1975-6 and Saigon had fallen on April 30, 1975. Or had been liberated, depending on your point of view. But why would one dislike American individuals, or the popular culture that everyone, including the French, consumed in massive doses?

🇨🇦🇫🇷

The year I spent in Paris made huge cracks in my personality. I began to feel that identity isn’t, or doesn’t have to be, a fixed thing. I recognized myself less and less when I returned to Calgary, to find my friends and their interests the same as when I left.

I came up with an explanation: when you go to live somewhere new, you expect to be confronted with differences. To be provoked and changed. When you return home you expect everything to be the same as when you left. You expect the changes to unchange themselves. Sooner or later, you realize that you’re no longer the same person. Or, you realize that you’re both the same old person and you’re also some new person. Later than sooner, you realize that this process will, if you want to experience and understand the world, continue till the day you die.

It took me a full year to find a rough (and temporary) balance between my old and new selves. Drugs didn’t help. Girls found me way too complicated. One thing that did help was a book I found at a friend’s house: The Texts of Taoism. Well, to be precise, the book didn't help me with girls, but it did help me with my identity crisis.

The authors suggested that you take life at face value and stop trying to impose your own view on it. They laughed at the idea of a fixed self, and wondered why one would even want one. I decided to try their advice, to follow my own tao or way, my own sense about things, worrying less about where this might take me or who I might become. I don’t know, who really knows who they are anyway?

The authors also suggested that there is a wonderful, deep, spiritual unity that lies hidden below the surface of personality, society, politics, and all that. This reminds me of k.d. lang’s song, “Constant Craving,” or the Sufi idea of “the Absent Friend.” I still don’t know about this, but I can’t say for sure that they’re wrong.

🇨🇦🇫🇷

Next: Train of Memory