Mesopotamia: From Sumer to Assyria

From museums in Paris, Rome, Berlin, & London

The name Mesopotamia comes from Greek and means between two rivers — in this case, the Tigris and Euphrates. Mesopotamians first developed agriculture, cities, numbers, writing, the wheel, astronomy, etc. For example, basic concepts like sixty seconds in a minute, sixty minutes in an hour, and 360 degrees in a circle seem to derive from the Mesopotamian numbering system, which used base ten and base sixty.

The major Mesopotamian civilizations are Sumer, Akkad, Babylon, and Assyria, and the study of these civilizations is called Assyriology. The early Sumerians spoke a non-Semitic language, yet the Semitic Akkadians who followed them integrated much of their culture. The Semitic Babylonians and Assyrians vied for control several times in the later centuries. Very roughly, this is the timeline:

3500 2500 1500 500

Sumer - Akkad - Babylon

& Assyria

Mesopotamians used the cuneiform script, which you can see in the Code of Hammurabi stele (immediately below). The first epic, Gilgamesh, and the first legal codes date back to the third millennium.

From the Louvre (Paris)

Above is the most famous version of the most famous legal code in Ancient history: the Code of Hammurabi. The Louvre website tells us: "This basalt stele was erected by King Hammurabi of Babylon (1792–1750 BC) probably at Sippar, city of the sun god Shamash, god of justice. [...] Two Sumerian legal documents drawn up by Ur-Namma, king of Ur (c. 2100 BC) and Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (c.1930 BC), precede the Law Code of Hammurabi. [...] The principal scene depicted shows the king receiving his investiture from Shamash. Remarkable for its legal content, this work is also an exceptional source of information about the society, religion, economy, and history of this period."

As in the Code of Hammurabi stele above, the Babylonian stele below also features the sun god Shamash, who was worshipped from around 3500 BC and who dispenses justice. In Gilgamesh, Shamash plays a key role in helping Gilgamesh defeat the ogre Humbaba (who protects the Cedar Forest where the gods dwell). The tension between Shamash and Enlil (the stern father of the gods) and his similarity to Ea/Enki (who saves humanity when Enlil sends the Flood), suggests that while Mesopotamian religion denies humans a meaningful afterlife, it's not indifferent to human fate.

Gudea, Prince of Lagash (c. 2120 BC) and his son Ur-Ningirsu (c. 2080). On the map above, Lagash is near the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. Lagash is next to Uruk and Ur, two of the most important and ancient Sumerian cities. Gilgamesh was king of Uruk, and Abraham is reported in the Bible to have come from Ur.

"Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, c. 2230 BC. It shows him defeating the Lullibi, a tribe in the Zagros Mountains, trampling them and spearing them. He is also twice the size of his soldiers. In the 12th century BC it was taken to Susa, where it was found in 1898." (Wikipedia)

From the Vatican (Rome)

Cuneiform was used in Mesopotamia for about three thousand years and then forgotten for about two thousand years (it was deciphered in the 1850s, three decades after hieroglyphics). These wedge-shaped marks in clay conveyed the first number and writing systems that we know of.

This inscribed envelop and the tablet inside date from about 1700 BC.

Inscribed cylinder of Nabuchadnezer II (605-562)

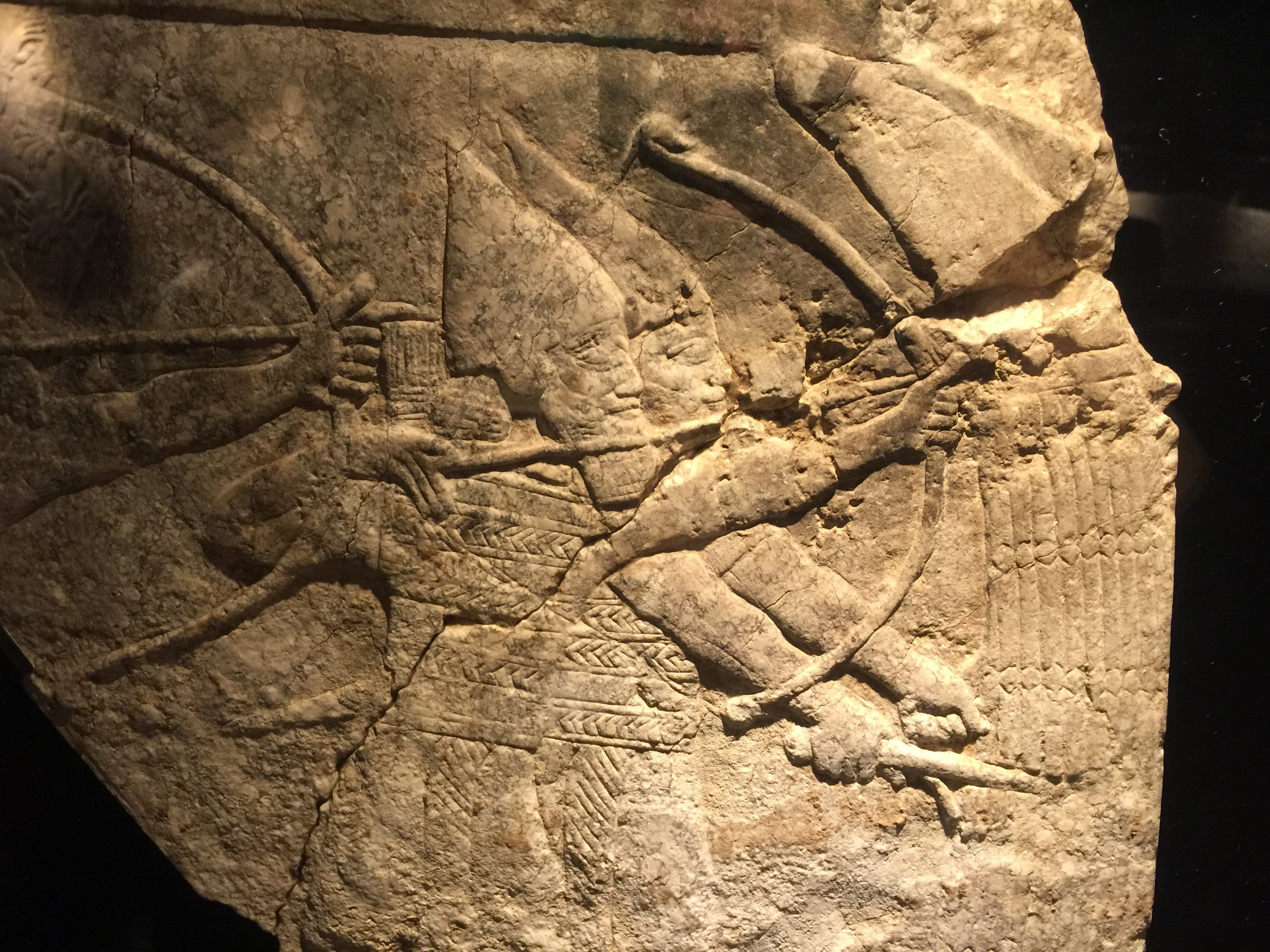

Assyrian archers in battle protected by a reed shield, Nineveh, c. early 7th C. BC.

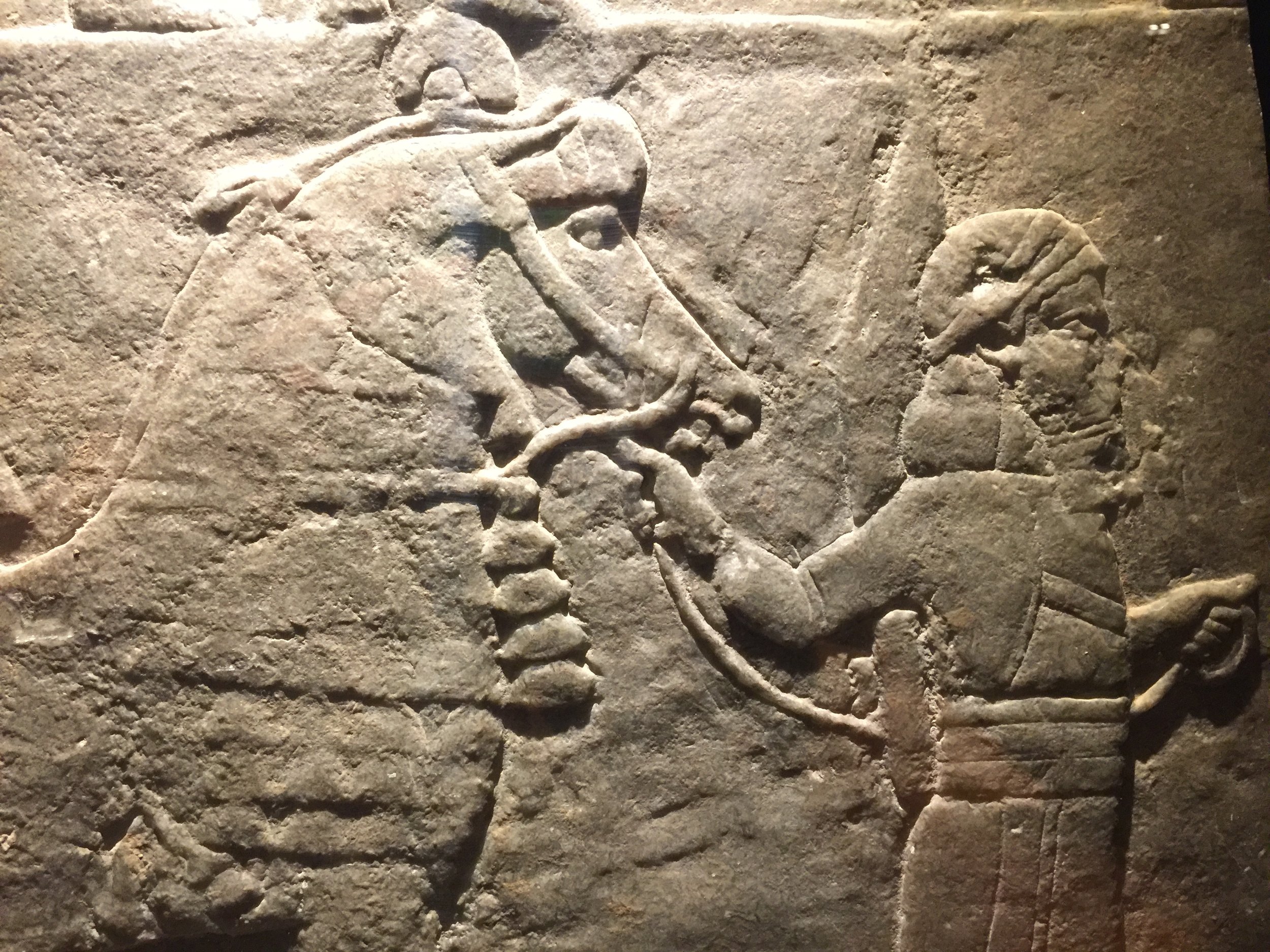

Elamite prisoners on a boat after the conquest of the city of Hamanu, late in the reign of Ashurbanipal, 7th C. BC.

Above: Arab tents in the desert set on fire at the end of the victorious Assyrian attack, 7th C. BC. Below: Eagle-headed winged genius worshipping the Sacred Tree, from the Palace at Nimrod, 9th C. BC.

From the Pergamon (Berlin)

The Gate of Ishtar was reconstructed in 1930 at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin from original bricks. The Gate was originally built in Babylon around 575 BC, during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC). It was dedicated to the goddess Ishtar, who dates back to the earliest Sumerian times, plays a major role in the epic of Gilgamesh (after being spurned by the hero, she unleashes the bull of Heaven), and influenced the development of the Phoenician Astarte and the Greek Aphrodite.