Gospel & Universe 🪐 At The Wild & Fog

From London to the Marabar Caves

A Passage to India - Only Connect - Back to Holborn Hill

🦖

A Passage to India

Pope asserts that the universe has a Plan, even though we can’t see it. Dickens understands that there are two plans — the old one of religion and the new one of science — yet he’s caught historically between the two, unable to chose one and reject the other. Less than a century later, E. M. Forster finds that the uncapitalized plan of science is more clear, having been proven over and over by an evolutionary theory which looks more and more like a fact. The very specific and by this time largely ahistorical (but still capitalized) Plan of the Bible, from Creation to Moses, is now far easier to lay aside. For many, the core of Christianity shifts from a Belief in a Plan which contains a version of historical events to a Belief in a Plan of forgiveness and love.

In his 1938 essay “What I Believe,” Forster makes it clear that he doesn’t believe with a capital B:

I do not believe in Belief. But this is an Age of Faith, and there are so many militant creeds that, in self-defence, one has to formulate a creed of one's own. […] Faith, to my mind, is a stiffening process, a sort of mental starch, which ought to be applied as sparingly as possible. I dislike the stuff. I do not believe in it, for its own sake, at all. Herein I probably differ from most people, who believe in Belief, and are only sorry they cannot swallow even more than they do. My law-givers are Erasmus and Montaigne, not Moses and St Paul. My temple stands not upon Mount Moriah but in that Elysian Field where even the immoral are admitted. My motto is: "Lord, I disbelieve — help thou my unbelief.”

Forster suggests that there is no grand religious Plan — certainly not of the Abrahamic Adam to Moses sort. Forster also suggests that even the most nebulous propositions of Hinduism are only confusing reflections of human emotions such as love and friendship. The veil of Maya or Illusion is itself an illusion, a sort of understandable comfort for those who can’t see that the highest mysteries are also muddles and for those who can’t appreciate the mysterious energies or ideas that drift between this world and the next. In this sense, Forster suggests that Maya is worth looking into, to see if perhaps one might get a glimpse of what lies behind it.

The process of arriving at truth in Forster seems a rather Hegelian one. In 3 Little Words, I argued that one of the ways to gain critical distance — the modus operandi of agnostic doubt — is through entertaining diverse and opposing points of view. One way to do this is explained by Zhuangzi: place yourself at the centre of the ring of thought so that you can respond endlessly to changing viewpoints. Another way is to use opposites in a fluid Hegelian manner, in order to find new and cumulative points of view, in a sort of progression or evolution in thought. In her Ph.D. thesis From Hegel to Hinduism: The Dialectic of E.M. Forster (1969), Clara Rising links Forster’s way of thinking to Hegel’s dialectic:

Dialectic is a term one should use with caution and some hesitation. It has been applied with equal authority to Socratic cross-examination (elenchus), Platonic dialogue, Aristotelian syllogism (categorical demonstration), Kantian transcendentalism (the second division of his Transcendental Logic Kant entitled "Transcendental Dialectic"), and to the so-called Hegelian triad of thesis, antithesis and synthesis (Dreischritt). I say 'so-called' because Hegel never used the terms "thesis, antithesis, synthesis." His method was much more spiritual than is generally supposed. The central idea which dictated the content and form of his Phenomenology of Mind is aufheben, the annihilation of, but at the same time the preservation of, each preceding step into a new metamorphosis which in turn demands its own annihilation and preservation, ad infinitum until one reaches Absolute Reality, Absolute Truth, Absolute Spirit. This is precisely Forster's method. Again and again, in story after story, in novel after novel, his characters, by annihilating and yet preserving previous concepts of themselves, through their experiences, through their knowledge gained in visionary moments — moments almost interchangeable with Hegel's description of self-consciousness-attain new levels of awareness which, depending on the intensity and quality of their experience, reach or fall short of that inner reality which is Forster's Holy Grail. Forster, like Hegel, refuses a synthesis, even when the last step — acceptance of all things through the subconscious-is taken. He is closer to Hegel than the others because Forster, like Hegel, carries his view of man beyond Aristotle's categories; both Forster and Hegel see the Absolute, unlike Plato, as a pervasive spiritual possibility rather than as a goal to be "reached"; both see the self, unlike Kant, as a substance capable of assimilating the Not-Self rather than as an autonomous entity retaining a dichotomy with the Ding an Sicht. With both it is the connection of contraries rather than the separation that is important. "Only connect" is Forster's cry throughout his work. We must, he believes, connect with nature, with other people, with ourselves, before reality and peace can be found. When such total connection occurs, it may cause death or disintegration of the character, but still this is not a synthesis, a closing in, so much as it is an opening out, the first step in a new dialectic of the spirit where the soul rises to ever widening experiences.

In agnostic fashion, Forster highlights connection of contraries, opening out and ever widening experiences. He assumes there’s no final relative truth, yet he’s open to the possibility of higher or more connected truths. Not surprisingly, he gravitates to Hindu thought, especially the type of thinking that we find in non-dualist Advaita Vedanta, which might be freely translated as the non-dual culmination of the ancient poetry of the Vedas. Advaita Vedanta is articulated most completely by the 8th century philosopher Adi Shankara, who emphasizes the omnipresence of God and the complete impossibility of understanding God.

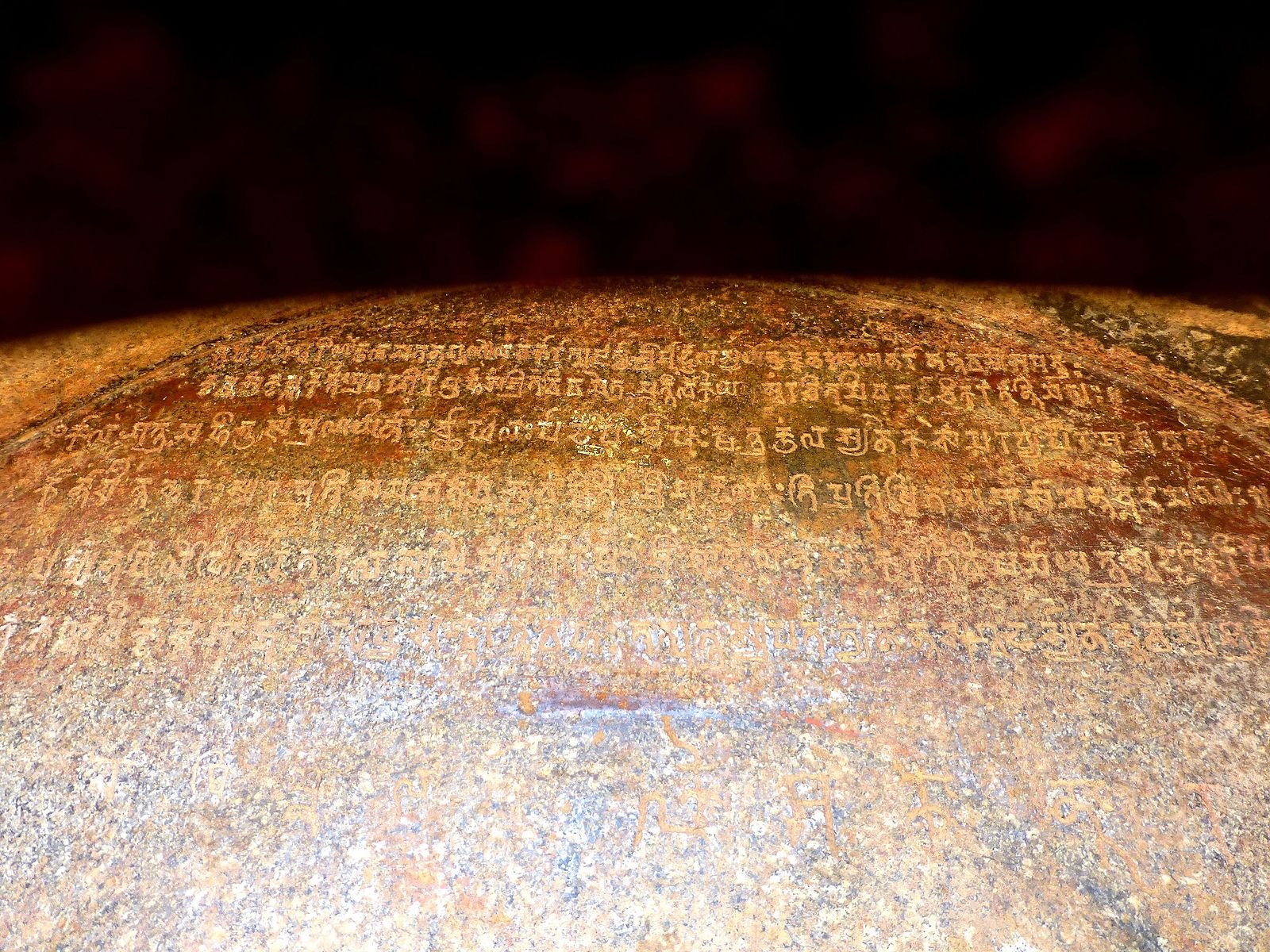

In A Passage to India (1924), Shankara’s general idea of non-dualism isn’t presented in traditional Hindu philosophical form, buttressed by assumptions about karma and samsara, and illustrated with references to Vedas and Upanishads. Rather, Forster suggests the union of opposites in the love that drifts between the characters, in the intuitions of connection felt by Fielding, Mrs Moore and Professor Godbole, and in the stubborn enigma of the Marabar Caves, a fictional version of the Barabar Caves Forster visited in 1913. The Marabar Caves are a fascinating invention: they echo the notion of a platonic cave, yet they also suggest an ineffable, terrible, awesome, confusing, ancient Spirit that reverberates everywhere. This Spirit is suggestive of Shankara’s Brahman, which might be characterized as the essence of God which pervades and transcends absolutely everything in the known universe.

🇮🇳

Only Connect

In A Passage to India Forster suggests that Hinduism is worth looking into. Much of what he writes reverberates with the Vedas, which were composed some three and a half thousand years ago. The Vedas are very different from the Bible in that they don’t supply a timeline of religious history. They are poetry, not history, the most well-known illustration of this being the comparison of Creation in the Bible and in Rig Veda, where only the god in the highest heaven knows how Creation occurred — or perhaps he doesn’t (10.129). Instead of providing chronologies and commandments, the Vedas offer paradoxes, piling question on top of question. As Wendy Doniger notes in her introduction to the Rig Veda,

The hymns are meant to puzzle, to surprise, to trouble the mind; they are often just as puzzling in Sanskrit as they are in English. When the reader finds himself at a point where the sense is unclear (as long as the language is clear), let him use his head, as the Indian commentators used theirs; the gods love riddles, as the ancient sages knew, and those who would converse with the gods must learn to live with and thrive upon paradox and enigma.

Historically, Forster has already detached himself from the literal religious Christian timeline prevalent prior to the 1850s, and this allows him to ponder a vaguer, more speculative timeline, one which starts obscurely (or has always been) in the inscrutable past, and continues indefinitely into the obscurity of the future.

We can see this timeline in all its obscure origins in the famous Creation hymn I referred to above from Rg Veda 10.129, where the poet suggests that only the highest god knows how Creation occurred, after which the poet says that perhaps the highest god doesn’t know this. Wendy Doniger writes that this hymn is “meant to puzzle and challenge, to raise unanswerable questions, to pile up paradoxes.” She also comments on another creation hymn (Rg Veda 10.72), where the poet tries in diverse and paradoxical ways to get at the incomprehensible. The idea of a mysterious muddle, what Forster ascribes to India and Hinduism, may be apropos:

This creation hymn poses several different and paradoxical answers to the riddle of origins. It is evident from the tone of the very first verse that the poet regards creation as a mysterious subject, and a desperate series of eclectic hypotheses (perhaps quoted from various sources) tumbles out right away.

Forster is agnostic in the sense that he doesn’t know whether or not there is a Grand Plan hidden somewhere amid all the paradoxes, ambiguities, and contradictions. Consequently, like the poets of the Vedas and like agnostics, he explores yet questions all religious narratives.

A Passage to India demonstrates a quasi-skeptical attraction to the least formulaic of these — Islamic mysticism (or Sufism) and Hindu mysticism, both of which suggest that we can’t define the soul or God in any clear sense. Both also suggest that if we destroy our limited selves (as in Sufism’s annihilation) or expand our selves (as in Hinduism’s moksha) we’ll see that everything, despite every evidence to the contrary, is connected.

Forster is attracted to infinite connectivity, as is clear in both A Passage to India (1924), where Godbole and Mrs. Moore embody a mysterious connectivity, and in Howard’s End (1910), where Margaret tries to get her husband Henry to open up to the connections all around him:

Only connect! That was the whole of her sermon. Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer. Only connect and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die.

Nor was the message difficult to give. It need not take the form of a good "talking." By quiet indications the bridge would be built and span their lives with beauty.

Forster follows this paean to unity and love with the blunt, “But she failed.” But the reason for Margaret’s failure is important: Henry refuses to open up, and instead he makes a fetish of concentration. This makes him unable to notice “the lights and shades that exist in the greyest conversation, the finger-posts, the milestones, the collisions, the illimitable views.” Zhuangzi would nod his head and say “I told you so,” and then wonder if this was necessarily true.

🇮🇳

A Passage to India focuses on the experience of the English protagonist Fielding, who enters the novel in the seventh chapter. One might say that Fielding’s name is appropriate, since he fields all sorts of things in the colonial world Forster has set up in the first six chapters. Fielding enters India late in life yet does his best to transcend his cultural background and see things with a fresh eye. He stays friendly with the British, yet he rejects their imperial isolation and their pretensions of superiority. Instead, Fielding spends most of his time with his Indian friends.

On a later page, Mysticism & Liberalism, I’ll argue that Fielding’s ability to go beyond his English upbringing is a sign of his liberal sentiments, which I’ll argue are a natural outcome of agnostic openness. Of course, the cause and effect here can be easily reversed: from Zhuangzi’s pivot of the Dao, liberalism and agnosticism are just two revolving points on the circumference of the ring of thought. Here, however, I want to focus on the religious side of Forster’s protagonist. I want to suggest that he’s a model of agnosticism: he remains skeptical and also open to new religious ideas and experiences.

Fielding is enamoured by the mystical poetry of his Muslim friends, yet he’s even more attracted to the enigma of Hindu mysticism, notably Godbole’s non-dual version of it. This isn’t surprising since Islam is surrounded by Hinduism in India, and since the infinite interconnectedness of matter and spirit that we find in the Sufism of Attar or Rumi is found in almost all versions of Hinduism.

While Hinduism is also riddled with terrible divisions when it comes to caste, and while recent political incarnations of Hindu nationalism aren’t encouraging, we nevertheless find in Hinduism a consistent emphasis on the experience of infinity, connection, and yoga (or union). There’s also a noticeable lack of dogmatic structure when it comes to religious philosophy: some schools of Hindu thought have an abstract God (Advaita Vedanta), some have a more anthropomorphic God (bhakti and Vishist Advaita Vedanta), most have many gods, and some ignore the notion of deities altogether (Nastikya). The sheer multiplicity of philosophic approaches, sacred texts, and theological stories makes it hard to insist on one text or one interpretation.

Also, the most popular and recent traditions — the non-dualism of Advaita Vedanta and the qualified non-dualism of Vishist Advaita Vedanta — agree that the highest truth can only be experienced and is therefore beyond words and doctrine. For instance, in his commentary on the Brahma Sutras, Shankara notes that our understanding of the Absolute (the realm of Brahman, which is everywhere and everything according to Advaita Vedanta) is predicated on a complete acceptance that we cannot know It:

By presenting Brahman as not an object on account of Its being the inmost Self (of the knower), they remove the differences of the "known", the "knower", and the "knowledge" that are fancied through ignorance. In support of this are the texts, "Brahman is known to him to whom It is unknown, while It is unknown to him to whom It is known. It is unknown to those who know and known to those who do not know" (Kena Upanishad II. 3), "You cannot see that which is the witness of vision, ... you cannot know that which is the knower of knowledge" (Brhadäranyaka Upanisad III. iv. 2), and so on. […] Even if Brahman be different from oneself, there can be no acquisition, for Brahman being all-pervasive like space, It remains ever attained by everybody. Liberation cannot also be had through purification, so as to be dependent on action. Purification is achieved either through the addition of some quality or removal of some defect. As to that, purification is not possible here through the addition of any quality, since liberation is of the very nature of Brahman on which no excellence (or deterioration) can be effected. Nor is that possible through the removal of any defect, for liberation is of the very nature of Brahman that is ever pure.

In one of the final scenes in A Passage to India, Fielding attends a Hindu festival. This allows Forster to flesh out what thinkers like Shankara explain in more abstract terms. One might even say that Forster gives a local habitation and a name to what might seem airy nothingness:

All culminated in the dance of the milkmaidens before Krishna, and in the still greater dance of Krishna before the milkmaidens, when the music and the musicians swirled through the dark blue robes of the actors into their tinsel crowns, and all became one. The Rajah and his guests would then forget that this was a dramatic performance, and would worship the actors. (Ch. 36)

Here Forster takes the notion of actors acting the role of gods, and turns it around so that the actors are themselves gods. This type of thinking is characteristic of Godbole’s thinking, and it is the very type of thinking that is so mysterious and disturbing to Mrs. Moore, whose name itself becomes a sort of mystical mantra by the end of the novel.

The Hindu festival illustrates the mix of chaos and oneness that is an inspiration, a communion, and a grand muddle. It allows Forster to engage with religion but without the type of historical and literal doctrines we find in Judaeo-Christianity and without the attachment to caste or sacred texts that we find in Hinduism.

The festival makes it clear (or at least as clear as Forster wishes to make it) that the Hindu notion of God is exceptionally elastic, and only Godbole is likely to know what it all might mean:

On either side of it the singers tumbled, a woman prominent, a wild and beautiful young saint with flowers in her hair. She was praising God without attributes—thus did she apprehend Him. Others praised Him without attributes, seeing Him in this or that organ of the body or manifestation of the sky. Down they rushed to the foreshore and stood in the small waves, and a sacred meal was prepared, of which those who felt worthy partook. Old Godbole detected the boat, which was drifting in on the gale, and he waved his arms—whether in wrath or joy Aziz never discovered. Above stood the secular power of Mau—elephants, artillery, crowds—and high above them a wild tempest started, confined at first to the upper regions of the air. Gusts of wind mixed darkness and light, sheets of rain cut from the north, stopped, cut from the south, began rising from below, and across them struggled the singers, sounding every note but terror, and preparing to throw God away, God Himself, (not that God can be thrown) into the storm. Thus was He thrown year after year, and were others thrown—little images of Ganpati, baskets of ten-day corn, tiny tazias after Mohurram—scapegoats, husks, emblems of passage; a passage not easy, not now, not here, not to be apprehended except when it is unattainable; the God to be thrown was an emblem of that. (Ch. 36

— words in bold by RYC)

I touched on this episode in Heraclitus: Athens & Allahabad, yet here I’d like to argue that Forster subtly stresses what I would call the inner passage that gives the novel’s title a double meaning.

The outer passage is that of ocean boats, British clubs, and the decades from Brahmo Samaj to Arya Samaj to the early 20th century Raj — and, unseen by Forster, to Independence in 1947 and the victory of the Bharatiya Janata Party in 2014. This is the outer layer of history, politics, and human relations, in the novel divided since 1600 by the ocean between England and India, and in the subcontinent divided since the Delhi Sultanate by the gulf between Hinduism and Islam. Fielding feels that this divide is unbridgeable in the present, but also sees the bridge as inevitable. Not now, but sometime in the future. Pulled, perhaps, by the invisible magnetism of the inner passage. A gulf that Sufi poetry and the echo of Shankara might in some way, always indefinable, manage to bridge.

The inner passage in the novel is the mystical, inexplicable connection that creates an echo in an ancient cave. This echo floats on the notes of Islamic poetry from the homes of Indians to the ears of Mrs. Moore. It floats over the water at a festival where Fielding starts to appreciate the vagueness of it all, the connection of it all, as Godbole and his Shankara wave at us from afar.

🇮🇳🇬🇧

Back to Holborn Hill

In Dickens, a megalosaurus waddling up Holborn Hill in the centre of London is a disquieting image, for it mocks the combined institutions of law, religion, and class that many felt were the bedrock of society. The megalosaurus also has a more subtle impact, one which can be felt on the level of intellectual history: it disrupts the old timeline from Adam to Moses. Like the discoveries in astronomy and geology before it, and like the discoveries in evolution and genetics after it, this striding gigantic fact of paleontology disturbs a millennia of understanding about what existence means. In the coming pages I’ll argue that it also works the other way around: the continued existence of non-literal monolithic religion — such as we find in mysticism and Hindu non-dualism — disturbs any type of complacent atheistical understanding of reality.

Science can be enlightening, yet it can also become what Medieval religion once was: a juggernaut, a huge and overwhelming force or institution which crushes everything in its path. In the case of science, it can be used to deny spirituality and to create nuclear bombs and global warming. Yet agnostics note that science also creates vaccines and the Internet. It doesn’t have a will of its own; it isn’t a philosophy. Rather, it’s what we make of it, and can be approached philosophically from at least three points of view: theist, agnostic, or atheist. In this sense, science is neutral — like the general concepts of law, religion, and class that Dickens aims to reform in Bleak House.

In this sense the juggernaut of science might also take the form of the original juggernaut: Jagganath, from Sanskrit, “Lord of the Universe.” We can pretend to drag the Lord from one spot to the next, yet where He is really taking us is a complete mystery. We remain, as ever, in the fog.

🦖

[In progress; see A Misty Maze, But Not Without A Plan for the complete eventual structure of this chapter]

🦖

Next: Almost Existential - Poor, Bare, Forked