Gospel & Universe ✝︎ Saint Francis: Pascal 5

The Cosmic Casino

Thou Shalt Choose - Without - Plato’s Cave - Pascal Revisited - Pascal’s Trap

✝︎

Thou Shalt Choose

Hounded by Pascal’s wager, or some variant of it, many people feel compelled to believe in Mysteries they don’t feel to be true in their lives or the world around them. Privately, I suspect, many believers suspect these Miracles are metaphors, not equations. But if they don’t follow the logic of the game, that is if they don’t make the leap of faith that turns like or as into is or are, they’re told they’ll end up in Hell.

Agnostics offer an alternative to Pascal’s wager. If you can’t believe in God — but can only hope that a benign and omnipotent Being exists — then you’re free to live your life in open exploration of the world around you. If there’s a God, you’ll wake up in an afterlife that’s the beginning of some new adventure. The Tour Guide will give the best itineraries to those who are devoted to a free and open exploration of whatever might be. He’ll assign desk jobs to those who made threats, telling customers that if they didn’t buy the All-Inclusive Package Tour then they’d end up in a small hotel with bars on the windows and a room temperature of 500 degrees.

✝︎

Without

Without imagination, life without a Grand Plan seems meaningless.

Without stone tablets we write our own laws.

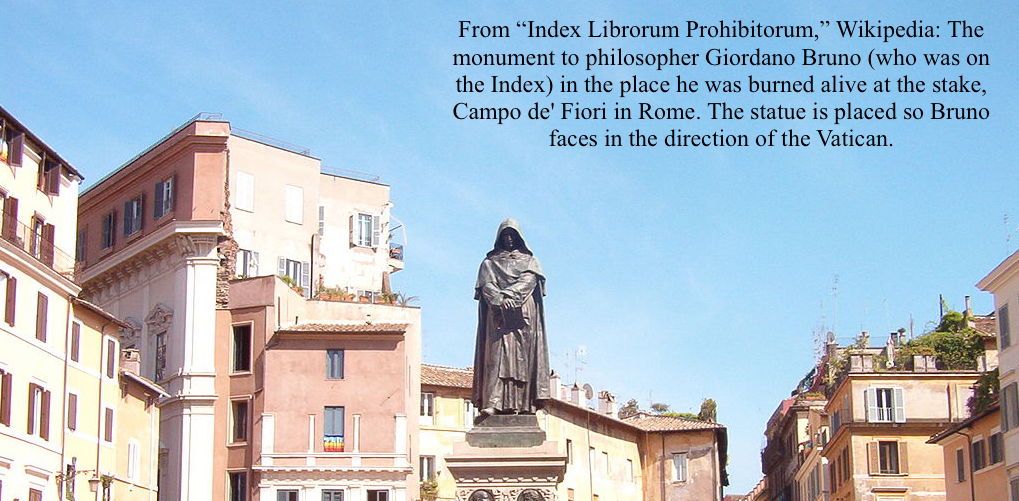

Without the Index of Prohibited Books we publish our own stories.

Without the Ideal Realm to which we must conform we are free to become who we really are.

✝︎

Plato’s Cave

Pascal tells us, it’s necessary to bet: il faut parier. But is it?

In “Plato’s Cave” (Season 1, Episode 4) of Rectify (2013), the protagonist Daniel is urged to believe in Jesus by Tawney, a well-meaning Southern Baptist. Daniel's response to her mixes Southern idiom and philosophic wit: Finding peace in not knowin’ seems strangely more righteous than the peace that comes from knowin’. For Daniel, doubt isn’t a negation of belief, but rather a ruthlessly honest form of belief.

Many Christians — not just zealots or fundamentalists — are in the grip of a coercive and dogmatic form of monotheism. This is a form of ‘spirituality’ in which they’re threatened by eternal torture and enticed by eternal happiness. This radical bifurcation is a false dichotomy on a massive scale. The psychological division this causes is only matched by the unbridgeable social and political division it creates between believers and non-believers, and between one group of believers and the next. Believing that your religion is greater than all other philosophies and religions is hardly a recipe for social or global harmony. Believing that your group alone knows the highest, deepest Truth is a recipe for disaster, especially when the exact same nonsense is drilled into the heads of young people all over the world, from all faiths. The nonsense appears, however, to be more prevalent, more deeply instilled, and more often insisted upon, in the Western religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

The words deepest and highest, when used to describe Truth, are conflicting vertical metaphors that don’t seem to bother religious fundamentalists, who believe that their Truth encompasses everything, from the depths of the earth to the heights of the distant galaxies. Scientists or agnostics, on the other hand, rarely profess a knowledge of deepest, greatest or ultimate Truth. As I argue in Aquinas & Dante to Summa Post Theologica (in Section 2. Religion: Christianity), this sort of totalizing belief system made some sense in the Middle Ages, yet it’s very hard for reasonable, rational people to maintain today. And yet still — in churches, synagogues, mosques, and temples all over the world — congregants are told that their specific religious Mystery trumps scientific mystery in general. Their Mystery is a Master Key to the gates of eternity, and it supersedes all the ‘minor’ mysteries that we’re yet to understand -- the four dimensions of space and time, the depths of the universe, matter, light, gravity, consciousness, etc.

Unable to appreciate the secular and democratic possibilities of metaphor, and unable to find deep wonder in a universe without dogma, many literalist Christians fall back on ideas such as Intelligent Design (which circumvents evolution), Predestination and the Elect (which justifies spiritual elitism), and Original Sin (which induces a deep sense of guilt, which then requires Grace or Redemption). Some fundamentalist Christians even suggest there's an anti-religious conspiracy among liberals, humanists, and scientists. Yet it’s precisely the opposite: investigating reality from every possible perspective is called freedom of enquiry. Exchanging views about these investigations is called freedom of expression. Conspiracy is much easier to find in the councils of the early Church, where they decided on dogmas that would last thousands of years, or in the closed-door meetings and the back-room dealings of the Vatican, where they continue to promote a male, heterosexual, elitist, and exclusive version of universal Truth.

Poets, scientists, and agnostics don’t believe in the metaphors they use. They understand that these verbal equations are in fact comparisons.

They understand that metaphor waits on reality, not vice versa.

In Words With Power (2008) Northrop Frye argues that literature is fundamentally iconoclastic:

As literature asserts nothing but simply holds up symbols and illustrations, it calls for a suspension of judgment, as well as varieties of reaction, that, left to itself, could be more corrosive of ideologies than any rational skepticism.

This iconoclastic tendency of literature applies doubly to poetry, which emphasizes the play and fluidity of verbal, intellectual structures. A poetic existence (one full of new experiences, perspectives, thoughts, and emotions) requires that metaphor be free to take us in new directions, so that we can ponder and feel the infinite possibilities and the interconnectedness of things. Dogmatists, on the other hand, take metaphor (a liberating cognitive device that allows the psyche to engage fully in analogy and empathy) and take away its meaning. They turn metaphor into equation, replacing flexibility and uncertainty with inflexibility and certainty. They replace fluid, open exploration of reality with fixed, eternal Miracles which they haven't experienced yet which no one's allowed to question.

I’d argue that some dogmas are possibly true (1), while others are arrogant and coercive (2 & 3):

1) God has a Plan for the universe and for each individual. This dogma is completely open to debate. Perhaps there's a Grand Plan, who knows? Who wouldn’t find it a great comfort if the universe had a Plan or Greater Meaning? And who wouldn’t be overjoyed to find that their life had a meaning greater than could be expected, given the material limitations of our short and often pedestrian lives? Who cherishes the thought of eternal night? Who doesn’t want to meet loved ones in the hereafter? Yet saying — or hoping — that these possibilities are eternal Truths doesn’t make them so.

2) The only way to truth and salvation is to believe in the particular Plan that involves embracing Jesus Christ. What might have been a wonderful option — to embrace a God of love and mercy, and to reconcile this with an earlier God of laws and punishment — was, unfortunately, turned into dogma: you MUST accept this particular version of God/Jesus. The largest problems with this doctrine are that 1) it assumes the existence of God and 2) it assumes that the believer knows that this God/Jesus doctrine is in fact God’s one and only Plan. How can one possibly know this? Humans cannot be sure of a Grand Plan, much less of a specific Grand Plan. Alexander Pope’s question (from An Essay on Man, 1734) is apropos here:

Is the great chain that draws all to agree,

And drawn supports, upheld by God or thee?

Pope presupposes the existence of God, yet he nevertheless emphasizes the fact that humans 1) don't control the universe and 2) are extremely limited in their understanding and range:

Say first, of God above, or man below,

What can we reason, but from what we know?

Pope's final answer to his own questions is that

All Nature is but art unknown to thee

All chance, direction, which thou canst not see.

His logic is of course circular: he questions man's inability to understand the Great Chain of Being, yet falls back on the certainty of that Great Chain. Yet this certainty contradicts his premise that humans are fatally limited. How can such a finite, imperfect being claim to know what the God of all time and space has in mind? How can such a human being claim that there is a Plan in the first place? Such a claim appears hopeful, even desperate in his Age of Reason, where thinkers like David Hume loomed in the shadows with much harder conclusions.

3) People will be damned for eternity if they don’t believe in this particular Plan. This is the Believe It or Else that adds threat to dogma. The idea that you must Believe it or else is a less subtle, more coercive take on Pascal’s idea that you should bet on belief because you have everything to gain and nothing to lose.

✝︎

Pascal Revisited

If the hellfire fundamentalists are right, they’ll be the ones to say,

in between sips of nectar, We told them so.

If the atheists are right, they won’t have that pleasure.

Details from The Garden of Earthly Delights (Hieronymus Bosch, 1503-15)

Pascal’s wager takes place in a casino where the game is fixed. His argument presupposes not only that believers know what the God of all space and time intends, but also that anyone who dares to explore alternatives will be damned for eternity. This is worse than arrogant: it’s manipulative and cruel. It should be called Pascal’s Trap. It also contains two wild assumptions. First, that by choosing belief you can influence the outcome, as if your will to have what you want will transubstantiate this life into the next. Two, that by choosing disbelief (or hope), your belief system (rather than your actions) will determine your afterlife fate. According to this, a repentant sinner goes to Heaven while a doubting philanthropist goes to Hell. The only people who benefit from such an absurd game are the casino owners.

The Hindu and Buddhist system seems more fair and reasonable, albeit equally hypothetical. In the doctrine of karma-samsara you simply get what you deserve. You can believe in the Blue Fairy and end up as a cockroach if you treat people like dirt. You can believe in the Purple Fairy and end up in a green land of doe-eyed maidens if you treat people with respect.

If God were reasonable and compassionate, He would censure or pity those who define Him narrowly. He would disdain those who damn others in the name of their narrow definitions. He would rejoice in agnostics and scientists who refuse to define Him in narrow terms, and who refuse to be slaves to fear, threat, and coercion. I would go further: if there’s a reasonable and compassionate God, He would let sincere agnostics and scientists into His Heaven more easily than fervent fundamentalists. If God weren’t reasonable and compassionate, why would one worship Him?

Fundamentalists would have us believe that truth and virtue lie in choosing a series of Miracles we can’t see or verify, and in agreeing to a very specific formulation of what these Miracles mean. We must believe in a magical Person who seems to be legendary (according to history), and whose words seem to be second-hand (according to Biblical scholarship). Who would even buy a car on such scanty information?

Fundamentalists would also have us agree with the decisions of the late Classical and Medieval councils that winnowed out different texts and points of view, arriving finally at a text and code of belief they felt to be absolute. What a strange conjuring trick: to operate within the flux of history and yet claim that your finished product is beyond history. And beyond doubt.

✝︎

Pascal’s Trap

Believing doesn’t make it so, and disbelieving doesn’t make it not so.

We don’t lose anything by not believing, except a two-sided coin, with a comforting conclusion on one side and a limiting delusion on the other.

Pascal writes with the assumption that we have everything to lose if we choose not to believe, but belief doesn’t mean we gain anything in the next life that we couldn’t get through unbelief, unless of course one subscribes to the notion of an angry, jealous God who punishes people for not intuiting an obscure possibility. Who would worship such a spiteful, entrapping God when Krishna and the Tao are on offer? Furthermore, by not deciding to believe, we stand to lose a delusion.

The one thing Pascal is right about here is that we can get some comfort or peace of mind by accepting a philosophical or religious conclusion. While this conclusion doesn’t guarantee anything in regard to the afterlife (again, thinking something doesn’t make it true), belief does allow the mind to rest from endless searching. It may also help us focus on positive things such as love and forgiveness. Yet trading truth for peace of mind sets a bad precedent. We are free to love and forgive without any sort of philosophical or religious injunction. In fact, loving or forgiving when you’re not constrained to or enjoined to, and when you have nothing personal to gain (such as Grace or eternal life), seems more altruistic or moral. Imagine doctors or nurses who go into the Congo and help people because they’re told that they must do this type of work. Then imagine doctors and nurses who go there simply because they want to lend a hand.

The Grand Plan of Existence — if, tiny creatures that we are, we can imagine such a Thing — may be to leave us in the dark. If there is a God, He/She (or more likely It) might frown on those who think they know Its mind or plans. Betting on knowing God’s mind may come with unforeseen consequences. It may be deluded, coercive, or dishonest to assert 1. that you have certain knowledge of a Grand Plan and 2. that you can make others cower before it, guilting and shaming them to believe in a Power and a Plan that no one knows. Likewise, to raise the stakes of your wager, implying that those who wager differently than you can lose everything — and in that everything lurks the old threat of eternal damnation — may be insulting to a Deity that cherishes love, reason, and forgiveness

✝︎

Next: Holy Dreamers