Cunning Plans

Gogol & Co.

Plans & Puppets - Cunning Plans

🌘

Plans & Puppets

And at the heart of Cunning Plans and section Puppet Masters lie Gogol’s Dead Souls (1842) and Koch’s The Year of Living Dangerously (1978). I use these two novels to try to get at the complex and colliding worlds that are laid bare (or lie hidden) beneath the surface of the present global crisis. For this reason I’ll delve a bit more into ❧ why I look at these two novels, ❧ how these novels are related to others I’ll use, and ❧ why Gogol is so central to my points about Putin’s war against Ukraine.

Cunning Plans takes a close look at Dead Souls (1842), Nikolai Gogol’s startling peek into the mind and manners of provincial 19th century Russia. Gogol’s novel also deals with Russian identity and with Russia’s stagnant social system.

Puppet Masters delves into The Year of Living Dangerously (1978), Christopher Koch’s depiction of 1965 Cold War Indonesia. Koch’s novel also deals with poverty, identity crisis, loyalty and betrayal, national and international conflict, and the difficulty of understanding who’s pulling the political strings. While the focus is on Indonesia, so much of what Koch writes about is germane to the new Cold War conflicts of the present crisis.

In Cunning Plans and Puppet Masters I also use a variety of other novels: Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita (a stunning novel that ranges from Pilate’s Jerusalem to Stalin’s Moscow), Greene’s The Quiet American (about the French in 1950s Vietnam), and Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children and Shame (about the Indian subcontinent in the 20th century).

Dead Souls and The Master and Margarita allow for historically-distanced yet culturally apposite critiques of Russian identity (and Putin’s version of this identity), while Year, The Quiet American, Midnight’s Children & Shame examine foreign forms of cultural and political expression, which will come in handy if we want to convince the rest of the world that the Kremlin is wrong.

🌘

Cunning Plans

Dead Souls and The Year of Living Dangerously are vastly different in style and content, yet they are also strikingly similar in some ways. Dead Souls delves into Chichikov’s absurd scam of selling souls, a scam which is echoed in Putin’s attempt to sell a special military operation that isn’t in the interests of Russian citizens. Similarly, Year delves into Sukaro’s attempt to sell communism to Indonesians and to back a communist coup, even though the Muslim and Hindu nation doesn’t want to live under a rigid atheist political system. Indonesians (especially their Muslim generals) reject Sukarno’s politics of revolution, in favour of a right-leaning capitalist democratic system (which doesn’t ignore the cultural diversity and tolerance already written into their national pancasilla philosophy).

I’ll use both novels to illustrate the Kremlin’s mistaken take on cultural identity and international order, and to suggest that we can understand the rest of the world better than the Kremlin can — if that is, we continue to avoid the colonial view that our culture, our politics, and our conception of the world are the only ones we need to emphasize.

In 🧥 Two Novels and an Overcoat I suggest that Gogol’s short story “The Overcoat” gives us a wonderful metaphor by which to ponder the Russian state of mind. What lies hidden beneath the Russian overcoat, pamphlets of rebellion or items to barter? Will Russians revolt against Putin or will they continue to swap his guarantees of security for their blind allegiance?

In 😵💫 Russian Souls and ✒️ Literature & Subversion I argue that just as Gogol’s townspeople are slow to figure out the scam perpetrated by the protagonist (Chichikov), so Russians are slow to see through Putin’s excuses for war and through his distorted notions of patriotism and the Russian soul. All of these are convenient ways to promote Empire, which ought to go the way of feudalism, serfdom, and colonialism. I’ll also argue that Gogol’s critique of Russian character and institutions is echoed in the Soviet-era writer Mikhail Bulgakov, and that this type of critique is more universal than some critics think: it isn’t just a function of a Russian soul, but of humanity in general.

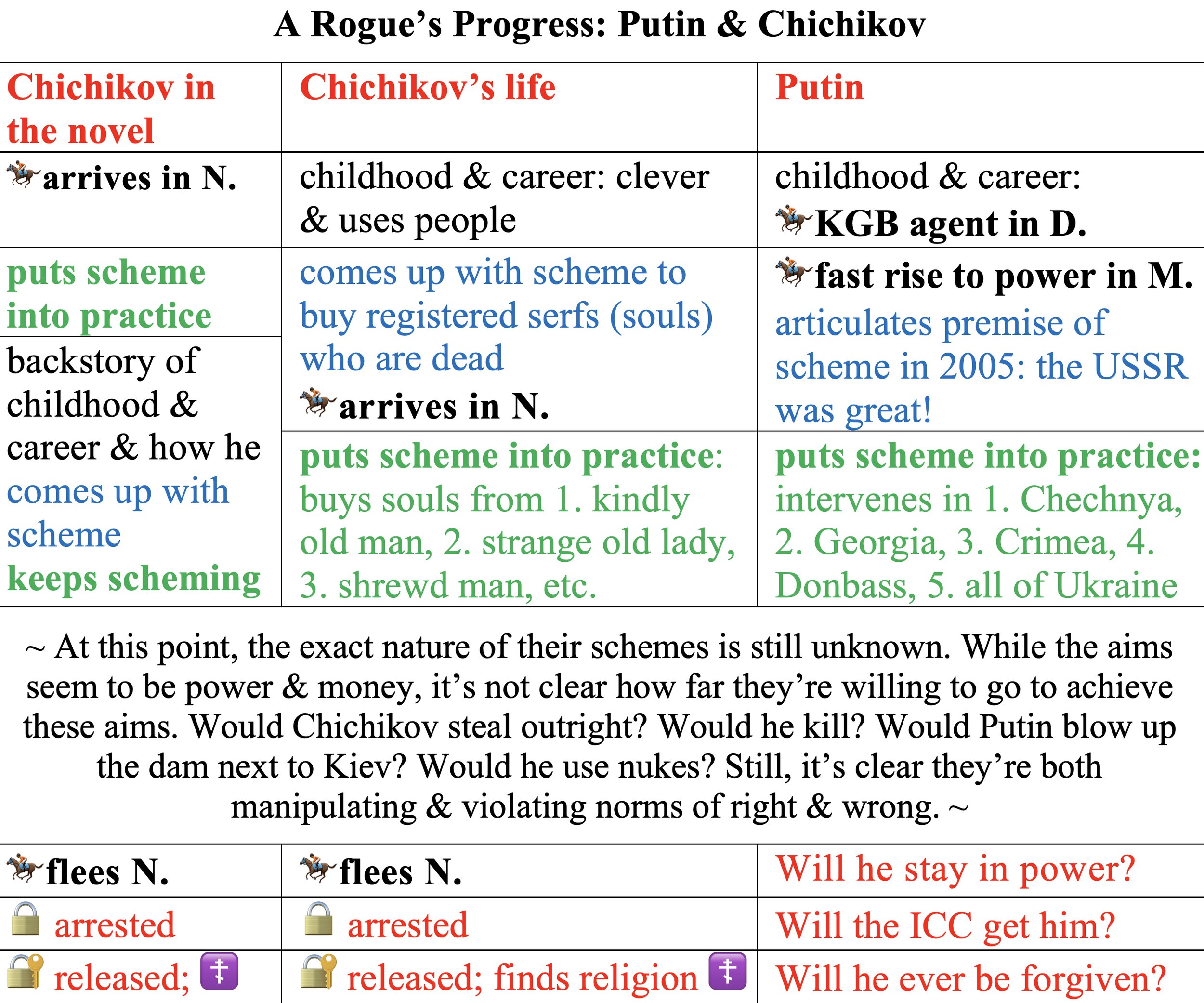

💰 Selling the Scheme (not yet online) looks more closely at Dead Souls, comparing how Putin sells his special military operation to the way Chichikov sells his scheme to buy dead souls (or deceased serfs):

Two other pages (not yet online) will look further into the issue of Russian motives and moralities: 🧛🏻♂️ The Immoralities of Marmeladov and Raskolnikov will look at the plans of Chichikov and Putin in light of the drunken logic of Marmeladov and the ruthless gambit of Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. 🚓 Crimes and Punishments will look at the crimes of Chichikov and Putin in light of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov and also in light of the justice and injustice of the world — a world in which the words of Shakespeare’s villain Claudius are all too true:

Gogol and Dostoevsky delve into similar ethical and religious problems, yet they ultimately fall back on tradition because they can’t find a satisfactory answers in the here and now. The troika at the end of Part One of Dead Souls represents Russia: it careens wildly into the countryside and forces everyone and everything in its path to give way. The cause of its wild flight is clear: Chichikov’s directive to the driver. This directive is like the homicidal will of Raskolnikov at the beginning of Crime and Punishment: both are selfish, lacking in principle, and fundamentally wrong. Like Putin’s special military operation. But unlike Putin, the Russian authors have the good sense to recognize this: Chichikov lands in prison and tries to repent his former ways, and Raskolnikov feels so guilty that he all but pleads with the police investigator to throw him in jail.

The authors’ solutions (or resolutions to use the literary term) are personal and moral rather than political or cultural. They address fundamental flaws in human nature, but they don’t expand this solution to address the cultural and political flaws that make society either free or enslaved. While Gogol offers possible directions for society in the lacklustre Part Two of Dead Souls, none of them answer the question, What forces in Russia can retain and reverse this willful careening?

There will always be Chichikovs and Raskolnikovs in society; what society needs is a system of law and societal custom that keeps them in check. Thou must not swindle, steal, murder, or invade thy neighbour is obvious to most everyone, but what to do with individuals who sideswipe these basic rules with their careening troika? And how to respond when they proclaim that their reckless flight is also moral and glorious?

Gogol or Dostoevsky don’t have the answers to Russian problems, yet they do raise fundamental questions. Later, Bulgakov also raises fundamental questions in his masterpiece, The Master and Margarita, written between 1928 and 1940. Because he was under the yoke of Stalin, Bulgakov can’t directly ask why the Soviet State forbids religion. Instead, he has the Devil himself descend on Moscow and punish the dogmatic Soviet atheists. He can’t ask why the Soviet State tyrannizes its people, so instead he has the Devil and his furious host play havoc with the bureaucratic system that controls poetry, art, and thought. Bulgakov thus hands out fictional punishments for those who collaborate with the authoritarian and dehumanizing system of the Soviet State.

Bulgakov’s case is different from that of Gogol and Dostoevsky, both of whom lived in a 19th century world of Western colonialism and nascent democracy. Yet for Bulgakov the alternate to authoritarian power had almost arrived: the liberal societies of the West had attained universal suffrage and were in the early stages of ending colonial rule (at least by his death in 1940). Western democracies were far from perfect — especially the fascist states of the 1930s! — yet in general they were far better to their own populations than the commissars, who reigned over purges, the Ukrainian Holodomor, the prison gulags, and the creation of a false narrative about communist equality and freedom.

Unfortunately for Bulgakov, Stalin refused to let him leave Russia. So he had to hide his manuscript of The Master and Margarita, which was finally published in a completely uncensored form in 1969, 29 years after his death.

When people like Putin yearn for the good old days of the Soviet Union, and when they go on about Russian culture and the Russian soul, just think of three names: Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn, Mikhail Afanasyevich Bulgakov, and Alexei Anatolyevich Navalny.

🌘