Gospel & Universe 🏛 Skeptics & Stoics

Nor Quite Stoic 2: The Bigger Picture

Stoicism & Agnosticism - Wide-Angle & Telescopic - For Anyone, But Not For Everyone - The Dangerous Sea

🏛️

Stoicism & Agnosticism

In locating two similarities and one difference between stoicism and agnosticism, I’ll pick excerpts from the eclectic, loosely-arranged maxims and paragraphs of Meditations. These excerpts will help to illustrate the way in which stoics and agnostics agree that 1. we ought to see life with a wide-angle vision and 2. we can’t be sure about the meaning of the universe. They’ll also illustrate the stoic notion that 3. we ought to accept the greater divine flow of Nature. The agnostic finds this third idea intriguing, yet also hopes that 2 and 3 don’t contradict each other as much as they seem to.

🏛️

Wide-Angle & Telescopic

In Meditations 9:30-31, Aurelius suggests that we take as wide of view of life as we can. He suggests that this view also has consequences: it makes us realize how small and insignificant our lives are — even if we were a Roman emperor, to whom memory and fame are key attributes:

Take a view from above – look at the thousands of flocks and herds, the thousands of human ceremonies, every sort of voyage in storm or calm, the range of creation, combination, and extinction. Consider too the lives once lived by others long before you, the lives that will be lived after you, the lives lived now among foreign tribes; and how many have never even heard your name, how many will very soon forget it, how many may praise you now but quickly turn to blame. Reflect that neither memory nor fame, nor anything else at all, has any importance worth thinking of.

[We should cultivate a] Calm acceptance of what comes from a cause outside yourself, and justice in all activity of your own causation. In other words, impulse and action fulfilled in that social conduct which is an expression of your own nature.

A great deal of philosophical and religious ink has been spilt on the topic of universal causes. Some even arguing that the only ultimate cause can be God. Aristotle says that we can’t know the first cause of the universe, yet Aquinas argues that it must be God. Atheists and astronomers don't assume this at all, and instead ignore the problem, leaving us in the causeless conundrum of what comes before the Big Bang, or in speculation about parallel universes or original surges which could mean anything or could come from anywhere.

Aurelius lived 2,000 years ago and of course didn’t have the faintest idea about a cosmogonic Big Bang, yet in terms of philosophy and theogony he cuts through this potential landmine of conflicting speculations: he says that because there are endless causes we can’t know, we should cultivate a philosophic detachment on the question of causes.

🏛️

Both stoicism & agnosticism try to see the big picture. Thinking in terms of geography, they try to see city beyond district, region beyond city, continent beyond region, world beyond continent, and universe beyond world. Stoics and agnostics see that within any given human realm, the fields which we see or understand have other fields next to them, and most often these adjacent fields overlap, intertwine, and interpenetrate. For instance, a farm field needs the nitrates from distant industry, and farmers sell their produce in distant markets.

What applies to tangible fields also applies to metaphorical fields: the field of biology is intricately interpenetrated by the field of chemistry, and physics operates everywhere in both. Humans aren’t only thinking machines, for logic lies next to emotion, and both of these mix to create psychology, which is constantly influenced by other people and by the organization of society — in other words by the field of sociology. Stoics and agnostics aren’t keen to draw sharp lines between these realms. In this context, they agree with Wordsworth’s phrase, We murder to dissect.

Of course in practical life we need to define things, set limits, prescribe guidelines. As in the painting above, we need practical things like buildings, steps, and bridges, as well as boats that can navigate beneath a bridge. Agnosticism assumes the value of these things, and in this sense has no antipathy or sense of superiority toward science and practical life. Yet agnosticism is a philosophy, and as such it’s less focused on things themselves than on the meaning of things. It’s about what it means to think about bridges and boats, what it means to chose a course through the water, and what it means to think beyond those things.

Because this beyond is so vast, and because it merges with other vastnesses, agnostics find it impossible to give this beyond a sharp contour or definite meaning. As in the painting above, the white and blue waters lift into the distance and up into the air, so that we can only guess where the water leads. We can only guess whether or not there’s a church in the distance, or is it a factory?

On Song of Myself 23, Whitman illustrates the interrelated and concrete way that the practical world relates to a poetic, mystical understanding of this world:

Hurrah for positive science! long live exact demonstration!

Fetch stonecrop mixt with cedar and branches of lilac,

This is the lexicographer, this the chemist, this made a grammar of

the old cartouches,

These mariners put the ship through dangerous unknown seas.

This is the geologist, this works with the scalpel, and this is a

mathematician.

Gentlemen, to you the first honors always!

Your facts are useful, and yet they are not my dwelling,

I but enter by them to an area of my dwelling.

When Whitman says “an area of my dwelling” I believe he’s saying that he looks closely at the practical side of life, with its reason and science, yet prefers to leave this realm for a different yet not contradictory one: the fierce combination of senses and energies that one might call a mystical or poetic connection. This is similar to the situation in “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” where Whitman tires of the scientific facts and glides out of the lecture hall, into the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time, / Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

🏛️

For Anyone, But Not For Everyone

Agnostics don’t expect everyone to be a philosopher. People can even be agnostic without knowing it. They can have a deep or enlightening experience without needing to delve into it with philosophic intent. They can question meanings and yet not arrive at any conclusion. Profound experience, coupled with uncertain conclusions, can be just as agnostic as a philosophical enquiry into agnosticism, such as this one.

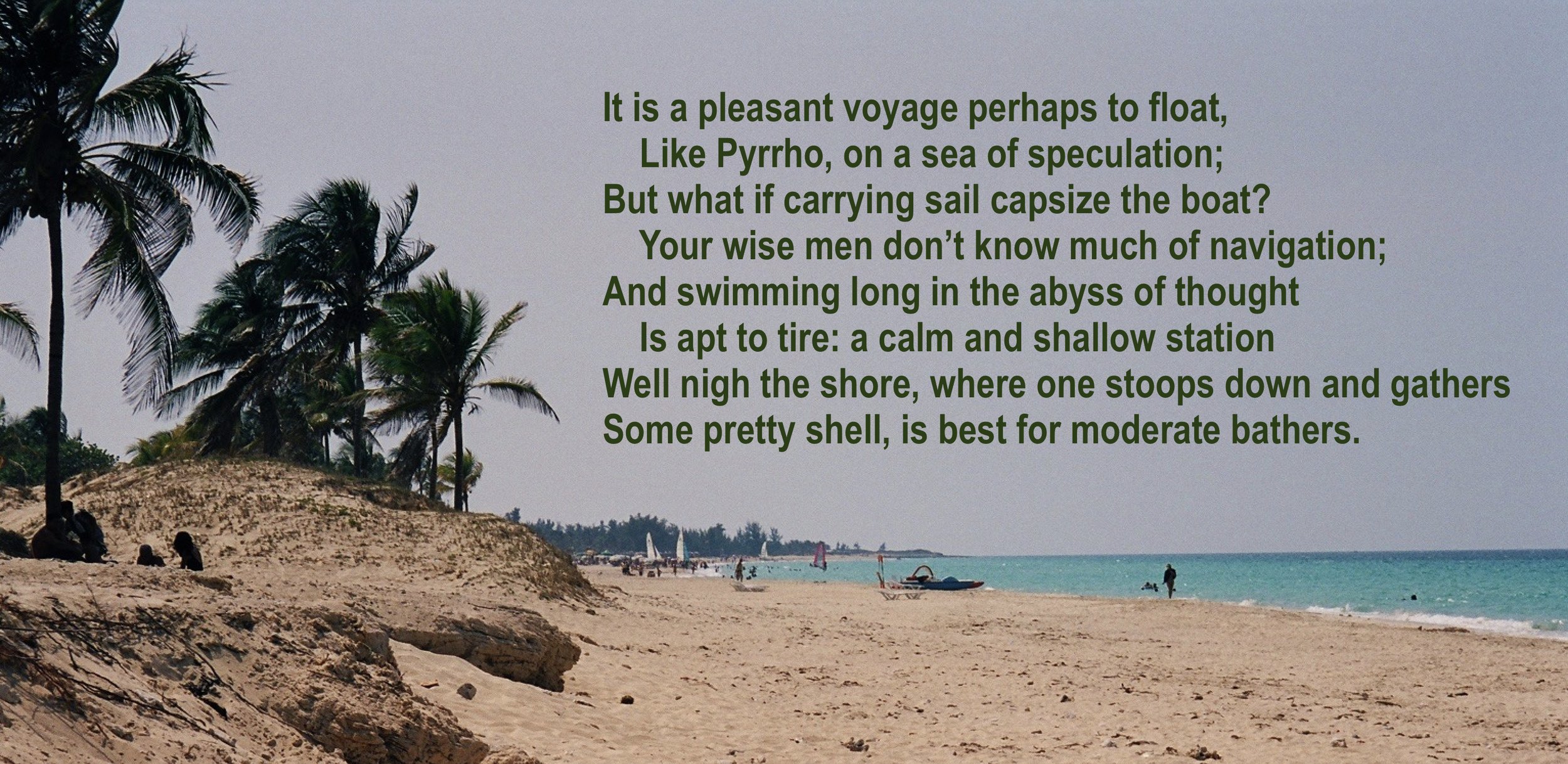

Unlike ministers and priests, agnostics don’t ask for any confession of faith, or any commitment to a book or set of guidelines. Pushing people into a demanding philosophical school like Skepticism or Stoicism may even be a recipe for disaster. Byron seems to have understood this:

Skepticism and Stoicism as formal philosophical systems are difficult, and require a fair deal of thinking about other philosophies and religions. Most people don’t have the time or inclination. And yet even the most practical questions about the meaning of life can lead to alienation and angst. This is one of the reasons that agnostics disagree with the New Atheists, who seem intent of prying people from their faith. Most people don’t have the time or ability to navigate the strong under-currents of philosophy, theology, and existentialism. In such a case, what’s the point of urging people to question beliefs that supply them with morality and meaning in an otherwise tempest-tossed world?

My concern here isn’t based on a fear that people might try new ideas and reject their old ones; that is a key element of critical thinking. Rather, my concern is that those who are well-versed in this type of philosophy ought to distinguish between belief which is harmful and belief which is helpful. They also ought to think about whether or not the person they’re talking to is able to operate in a philosophical manner, unmooring their boat and letting it drift into an indeterminate sea.

🏛️

The Dangerous Sea

In the final chapter of Part I, I look at the scenario in the 1967 lyric “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” arguing that the protagonist wants to stay in the comfort of the human bar while the epic heroine wants to test the challenges of the open sea. I argue that the heroine is an existentialist who means every word she tells the protagonist — “There is no reason” — even though the protagonist tries to come up with all sorts of reasons to avoid her depressing existentialist vision, her conclusion that turns her face, at once just ghostly, a lighter shade of pale. The protagonist tries, with no success whatsoever, to make light of philosophy, suggesting that she’s so sexy that she could tame even the lord of the seas: “You must be the mermaid / who took Neptune for a ride.' / But she smiled at me so sadly / that my anger straightway died.”

I go into much more detail in my analysis of the lyric, in which I use the less-known, more complex four-stanza version of the lyric. Yet one point I don’t make in that chapter is that the heroine may not be right in taking the protagonist along with her on her journey. Is he really ready for it? Probably not, since he seems to see it in terms of capsizing the boat and hitting the ocean floor. The last line of the four-stanza version is, “So we crash-dived straightway quickly / and attacked the ocean bed.”

The sea is Neptune’s realm, and ever since the early Greek epics it’s been a very dangerous place. The Greeks sailed routinely all over the Mediterranean, from Crimea to Marseille, and the journeys of Jason and Ulysses attest to the dangers. In “Tales of Brave Ulysses,” another popular song written in 1967, moving out into the open sea is referred to as riding “upon a steamer / To the violence of the sun.” This epic journey southward contrasts with remaining in the bleak (presumably English) winter that is dangerously depressing: “You thought the leaden winter / Would bring you down forever.” Yet the southern temptation, which might stand for several forms of escapism (especially drugs and idealistic sexual fantasies), has a hidden danger, one which is expressed in terms of the well-known episode of the sirens in The Odyssey. The psychedelic liveliness of this ocean trip may seem like a utopia, yet it might also overwhelm your system: the sea’s bright colours might “bind your eyes with trembling mermaids,” one of which may “drown you in her body, / carving deep blue ripples in the tissues of your mind.”

Setting out into the open sea isn’t an easy thing, as even the popular songs “A Whiter Shade of Pale” and “Tales of brave Ulysses” insinuate. Likewise, dropping the ties which connect you to what your parents believe or what you’ve been prepared culturally to believe, isn’t an easy thing. The quest for truth isn’t an easy quest, and agnostics might keep Byron’s stanza mind: give people some warning when you encourage them to sail out into seas that you know to be unpredictable and dangerous.

Like outer space, the sea is a powerful symbol of infinity and the unknown. One might argue that the sea is slightly more scary, since it’s murky depths can be reached all-too easily. In any case, both are symbols for the more extreme expansion that agnostics attempt to understand. But careful agnostics aren’t zealous to make others think too much about the bigger view.

🏛

People will wander along the beach, and look under a dock.

Or they’ll drink mojitos with their wife, a crazy Dutchman, and his Bolivian partner, the blue sea safely in the distance.

One day they’ll sit on the beach, watching the girls or gathering pretty shells. Another day they’ll swim out into the shallows, feeling the pull of the deeper waters.

🏛️

Next: 🔭 The Sum of All Space - Third Spinning Rock from the Sun

[Nor Quite Stoic 3: The Uncertainty of It All is in progress]