Gospel & Universe ⏯ Systems

Systems of Dread & Hope

Multiples of Hope - The Dreadful Truth - Egypt: From Dread to Hope - Persia - Greece: From Shades to Sunlight

⏯

Multiples of Hope

There are of course many ways to categorize religious systems, yet one key way is to look at the way they deal with the question of the afterlife. This is often a very complex matter, and often evolves with time. For instance almost all Christians today believe in an afterlife, yet Ecclesiastes 3:19-21, considered among the wisest of texts, contains the following:

All have the same breath; humans have no advantage over animals. Everything is meaningless. All go to the same place; all come from dust, and to dust all return. Who knows if the human spirit rises upward and if the spirit of the animal goes down into the earth?”

Likewise, about death Zhuangzi says that what “we can point to are the logs that have been consumed; but the fire is transmitted elsewhere, and we know not that it is over and ended”;

The whole process is like the sequence of the four seasons, spring, summer, autumn, and winter. While [my dead wife] is thus lying in the great mansion of the universe, for me to go about weeping and wailing would be to proclaim myself ignorant of the natural laws. Therefore I stopped! (The Texts of Taoism, trans. James Legge)

⏯

The most obvious categorization of afterlife systems is 1. systems that deny an afterlife, 2. systems of Heaven & Hell, and 3. systems of reincarnation or samsara. One could also see these three categories in terms of hope and justice: 1. systems which don’t provide for an afterlife, and hence don’t provide an afterlife justice — neither a hope for afterlife reward nor a fear of afterlife punishment; 2. & 3. systems of universal justice, which supply an afterlife which is based on the merits of an individual, whether this by in a fixed otherworldy location like Heaven or Hell, or and 2. & 3. systems of grace, which offer a positive afterlife even to those who lack merit.

Systems of universal justice supply a simple, ruthless, democratic standard which entails a fair judgment and no exemptions. One might call this a double hope, in that it contains 1) the hope that there’s an afterlife, and 2) the hope that we will be judged fairly after we die. Systems of grace involve a triple hope, in that they contain the two hopes above, as well as 3) the hope that despite our shortcomings we’ll still be graced with a positive afterlife.

While the early Mesopotamians, Jews, and Greeks denied their believers a clear or enjoyable afterlife, other more optimistic systems developed — most notably the blessed afterlife of Egyptians and Persians and the reincarnation of Greek Platonists, Hindus, and Buddhists. Because we only live seventy odd years and because everything we know lies within our experience of those years, it’s quite natural to want to continue our existence. The finality of death is otherwise a shocking, absurd, brutal truth. The idea of a dark gloomy afterlife (like we find in early Mesopotamia and Greece) doesn’t really help: it only turns the possibility of eternal life into a depressing never-ending affair. No afterlife or no enjoyable afterlife make sense in theologies where humans are of no account, where the powers that be (to paraphrase from King Lear) treat humans as flies to wonton boys, who kill them for their sport. Conversely, the more we believe the universe to be benevolent, ordered, and run by merciful powers, the more we’re likely we are to hope that these powers have provided us with an extension of the life to which we have become accustomed.

⏯

The Dreadful Truth

For the Mesopotamians, the afterlife was a dim, murky affair. This can be seen in the ancient story of Gilgamesh. Before their battle with Humbaba, Gilgamesh tells Enkidu:

All living creatures born of the flesh shall sit at last in the boat of the West, and when it sinks, when the boat of Magilum sinks, they are gone.

In another instance, souls go down to a dark underworld, yet their state of existence can hardly be called an afterlife: their ghosts flit like broken birds amid the dust, ruled by silence and the grim Queen of the Deep, Ereshkigal. In Gilgamesh, Enkidu has a dream in which he’s dragged by a vampire-faced bird-man “to the house from which none who enters ever returns, down the road from which there is no coming back.” In this place, those who were high and mighty on earth “stood now like servants to fetch baked meats in the house of dust.”

In the Mesopotamian afterlife, there’s no room for a hope that contains eternal meaning or bliss. This quasi-existential point is pounded home to Gilgamesh first by the alewife Siduri and then by Utnapishtim. Distraught by Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh searches for Utnapishtim (the polytheistic version of Genesis’ Noah), the one human who “entered the assembly of the gods, and has found everlasting life.” En route, Siduri tells him,

You will never find that life for which you are looking. When the gods created man they allotted to him death, but life they retained in their own keeping.

Once Gilgamesh reaches Utnapishtim, the latter is equally clear:

There is no permanence. Do we build a house to stand forever? Do we seal a contract to hold for all time? [...] It is only the nymph of the dragon-fly who sheds her larva and sees the sun in his glory.

Gilgamesh will never again see his dead companion Enkidu, and he must resign himself to find meaning in the world of the present. He must content himself in doing what he should do: become a just and merciful king in the great city of Uruk.

⏯

Egypt: From Dread to Hope

Exactly why or when the grim vision of the afterlife changed north of Egypt is a matter of debate for scholars of the early Classical world. Yet it’s not hard to see how the more hopeful Egyptian type of afterlife system would supply people with greater philosophical meaning and greater moral incentive to act benevolently. Whether or not the Egyptian view influenced the Persians or the later Mesopotamians, Hebrews, and Greeks, it seems that something like it was adopted sometime in the first millennium BC.

Here’s the full version of the Encylopedia Britannica entry I quoted two pages earlier (in Post & Other Scripts):

It was thought that the next world might be located in the area around the tomb (and consequently near the living); on the “perfect ways of the West,” as it is expressed in Old Kingdom invocations; among the stars or in the celestial regions with the sun god; or in the underworld, the domain of Osiris. One prominent notion was that of the “Elysian Fields,” where the deceased could enjoy an ideal agricultural existence in a marshy land of plenty. The journey to the next world was fraught with obstacles. It could be imagined as a passage by ferry past a succession of portals, or through an “Island of Fire.” One crucial test was the judgment after death, a subject often depicted from the New Kingdom [c. 16th-11th C. BC] onward. The date of origin of this belief is uncertain, but it was probably no later than the late Old Kingdom [c. 27th-22nd C. BC]. The related text, Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, responded magically to the dangers of the judgment, which assessed the deceased’s conformity with maat [the personification of truth, justice, and the cosmic order]. Those who failed the judgment would “die a second time” and would be cast outside the ordered cosmos. In the demotic story of Setna (3rd century BCE), this notion of moral retribution acquired overtones similar to those of the Christian judgment after death.

It seems more than likely that the specific idea of an afterlife land of the blessed was influenced by the positive afterlife scenarios in Egypt and Persia. In the Egyptian afterlife judgment, if your heart is light you go to a lush garden. If your heart is heavy and it weighs down the scales, then your soul will be thrown into flames. This is an ingenious scenario, since it leaves the world brighter each time: good people continue to exist, while evil people are erased entirely. Dark and nasty places like Hell are not required. There are no endless prison riots or gnashing of teeth.

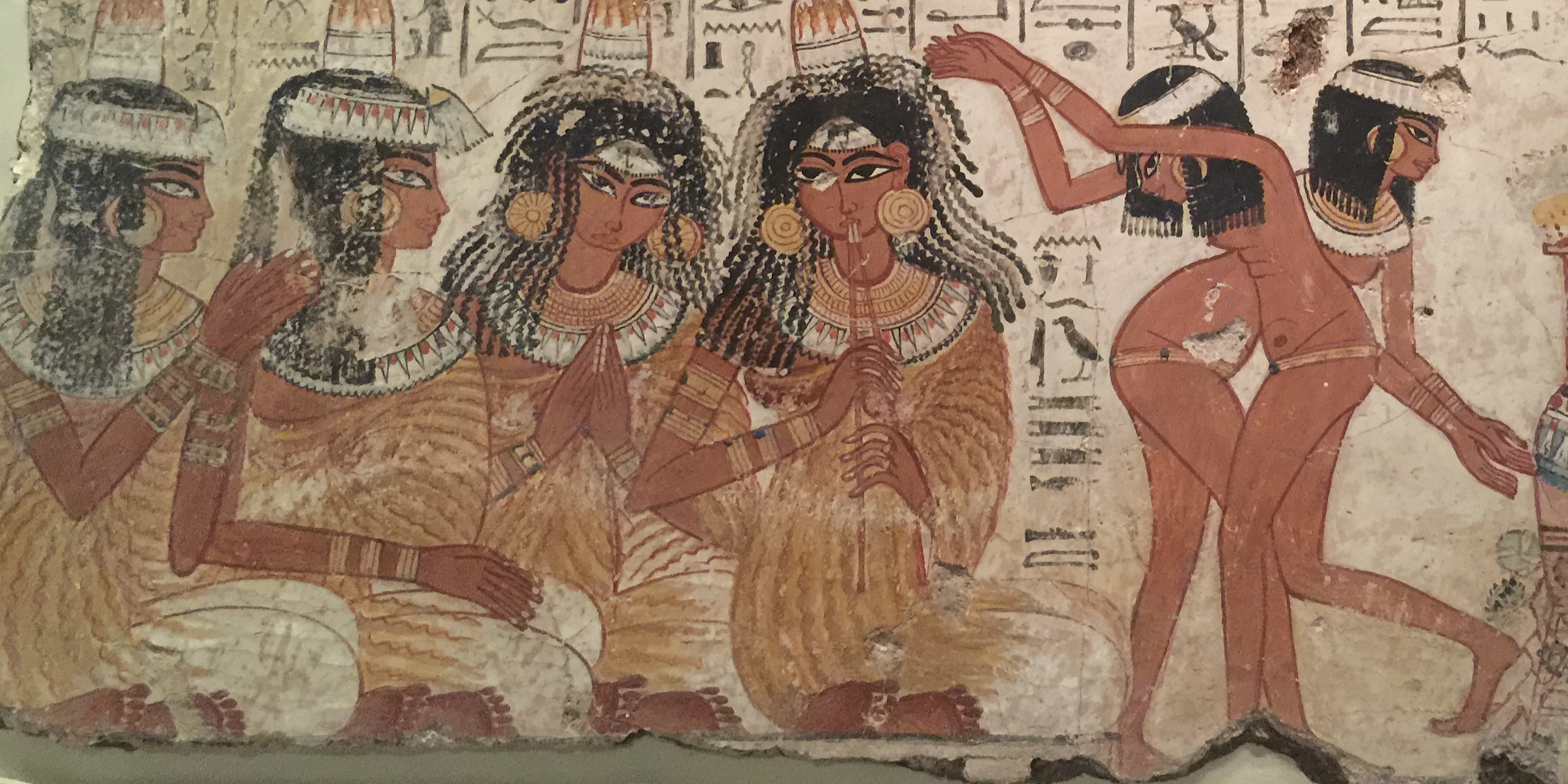

Because the Mesopotamians only marginally believed in the afterlife, they didn’t need an elaborate afterlife judgment system. Their grim view seems to be similar to that of the early Hebrews and Greeks. Perhaps this quasi-existential vision was simply too pessimistic, especially compared to the more optimistic vision of the Egyptians, where one could live eternally in a garden if one lived morally during one’s lifetime. One could imagine oneself living forever the kind of happy life one lived on earth, the type of life painted on the interior of Nebamun’s tomb:

⏯

Persia

The Zoroastrian Persians may also have had an influence on the positive afterlife scenarios that developed in the late Classical period and that provided Judaism and Christianity with greater motivation than the grim Mesopotamians scenarios. Based on early Indo-Iranian religion and on the teachings of the obscure figure Zoroaster or Zarathustra (c. 1000 BC), Zoroastrianism contains the following:1) a supreme being (Ahura Mazda) who wins a cosmic battle over a satanic figure (Angra Mainyu), 2) free will to choose good or evil, 3) the notion that you sow what you reap, 4) an afterlife journey (over a bridge) at which point the soul is judged, and 5) the belief that everyone will eventually be redeemed from their sins (this includes even the worst of sinners, as with the early Christian thinker Origen).

⏯

Greece: From Shade to Sunlight

The transition from hopelessness to hope can be seen in Homer’s epics. In the Iliad, death seems a bleak prospect:

Certainly Achilles’ fate in the Iliad conforms to its view of death generally: such forms of immortality as the apotheosis of mortals, worship as a cult hero, or translation to a White Island or Elysian Plain are passed over in virtual silence. The heroes of the Iliad look ahead only to Hades’ dismal realm. (Anthony Edwards, “Achilles in the Underground,” 1985)

And yet when Odysseus travels to the underworld and talks to Achilles in The Odyssey, Achilles says that he’d gladly swap places with a poor labourer above ground:

How didst thou dare to come down to Hades, where dwell the unheeding dead, the phantoms of men outworn. [...] Nay, seek not to speak soothingly to me of death, glorious Odysseus. I should choose, so I might live on earth, to serve as the hireling of another, of some portionless man whose livelihood was but small, rather than to be lord over all the dead that have perished. (The Odyssey, trans. A.T Murray, 1919)

It’s hard to make out clearly the topography of this Greek realm. Perhaps this is because there were different models of the afterlife, reflecting current and earlier models, such as those that came from the Mycenaeans and Minoans:

Belief in a realm of Hades was complemented by an alternative land of the blessed, usually an island located at the edges of the earth, where kings and other favoured individuals enjoyed a happy eternity. Although it remains unclear just how this eschatology fits into the religious thought of pre-classical Greece, the idea of such an afterlife is generally agreed to go back at least to Minoan-Mycenaean times. (Anthony Edwards, “Achilles in the Underground,” 1985)

⏯

Next: Currents of Christianity