Gospel & Universe 🧩 Complexities

The Mysterious Heavens

Andromeda to NGC 224 - The Mystic Astronomer - Giordano Bruno

🧩

Andromeda to NGC 224

The moon was once a friendly thing, full of mystery and seduction. The Chinese poet Li Bai hoped that one day he would meet it, deep in the Milky Way.

The moon was mysterious and seductive, and the sun was a god.

Then the fine glass of Venice made its way into the telescope of Galileo. While some ignored it back then, today we still feel it: the ground moved.

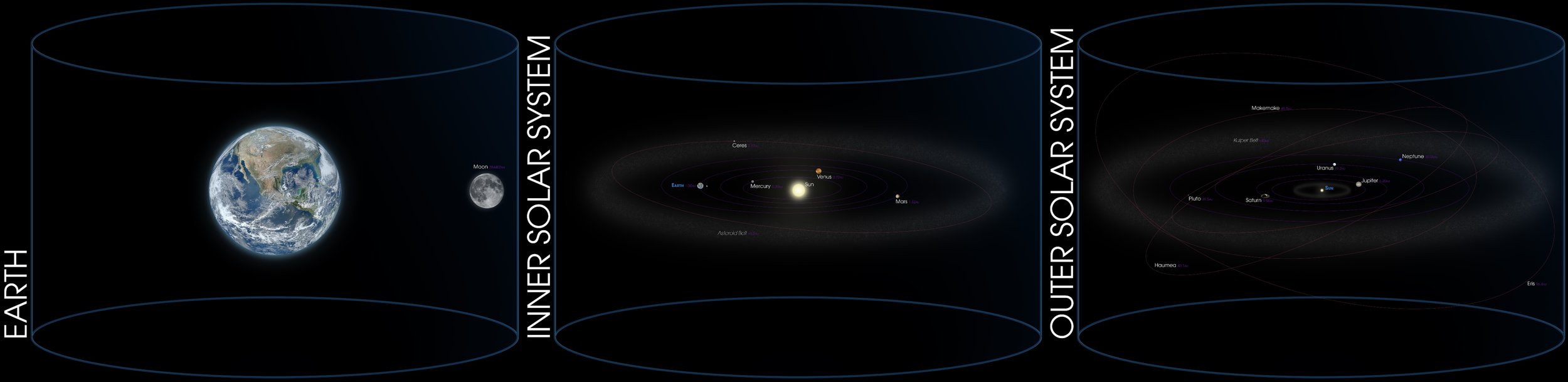

And it kept moving. Over the next several hundred years, we saw that it moved in three ways: it spun on its own pole, it circled around the sun, and it circled around the centre of the Milky Way.

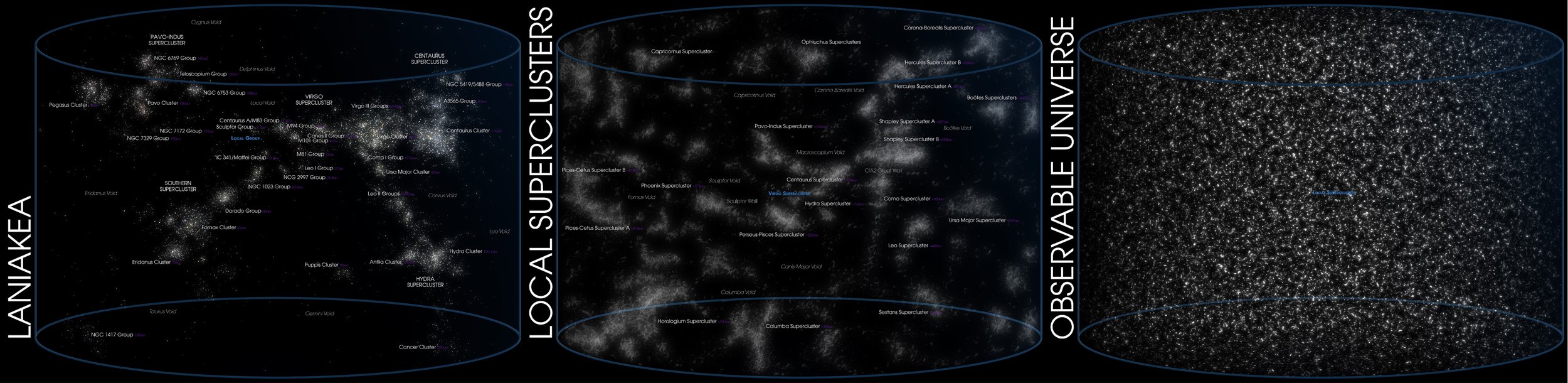

In the 1920s another radical shift occurred, which was both tectonic and astronomical: the Milky Way wasn’t all there was to space, and the Milky Way was itself moving in relation to other, similarly large conglomerations of stars. Any patch of Earth on which we stood now moved in more ways than three — this time toward Andromeda and toward the Great Attractor, and toward somewhere in the heavens that we still aren’t sure about.

Sitting at a table at 4 AM, everything seems still. The table top is a circular slice of marble, the cup is a hollowed-out circle of porcelain china. The coffee is in the cup. The surface is like a dark lake, a pool that reflects the world around me. I remember a boat bobbing in a harbour thousands of kilometres away. I remember an ocean kilometres deep. The pool becomes a well of memory, and I can’t see the bottom.

While I’m sitting next to the circular table, I know that we’re all circling the earth, the solar system, and the galaxy, and that we’re also moving and circling in ways we cannot count, moving toward any number of astronomical points that are yet to be determined.

The sun god became a statue. Andromeda became NGC 224.

The Son of God became a tale. Or did he?

After the 1920s, when so many new horizons swam into our ken, the old notion of an unknowable Infinity reappeared. Or did it?

Dante’s far-off circling worlds couldn’t be seen at the end of Galileo’s telescope. Nor could they be seen when Hubble looked upward in 1922 to the uncharted skies, to the profusion of galaxies beyond Andromeda. And yet the staggering immensity was enough to make any one of us lose our grip, to turn awe into mysticism, just when we were starting to feel confident about the scientific explanation. Just when it looked like we were starting to understand the universe and our place within it.

In the 1850s Darwin showed us the mechanism of evolution, and philologists showed us that the old holy books are human narratives. The biblical Noah is the Sumerian Utnapishtim. The Great Flood happened long before Noah built his ark.

In the 1920s Hubble showed us the existence of other galaxies, and Koltsov and Griffith showed us that our bodies, as well as our inherited traits, are a function of DNA. All of these discoveries upset deeply-held religious views, yet they also advanced scientific understanding and showed us who we are and how we got here. The scientific explanation was close to complete. Even to one without faith, an explanation was now possible.

Much has been made of the unsettling nature of Darwin’s articulation of evolution (I have stopped referring to it as a theory), yet I’d argue that the most deeply disturbing — and most deeply fascinating — discovery was made by Hubble. Darwin showed us that we evolved rather than were created, but this still allowed us to explore and understand who we are. Yet Hubble showed us that we’ll never understand the nature of the universe. The realms of undiscovered space are simply too large for use to say with any certainty what’s out there. We’re forced by science and by reason itself to admit The Great Unknowability of Things.

Spinning, the dervish astronomer sees the atoms spin, lost in a purple sky deep as galaxy UGC 12158.

🧩

The Mystic Astronomer

With spectrographic eyes and red-shift ears, science scanned poetry

and with heels brighter than Mercury when he circles closest to the sun

poetry leapt into science. Like Keats’ Cortes in a distant land,

what we once couldn’t see now swam into our ken:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortes when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific – and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise –

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

The scientist was astounded, agog to see the contours of this galaxy and the next

to see God wheeling infinity from quadrant to quadrant.

The astronomer just sat there with his friend, the physicist, with mouth open

ready to believe now in anything

even that within the clouds of knowing were winds unknown

and that winds unknown were blown by currents unseen;

that unknown poles were turning our galaxy

and that deep within substructures of matter were spirits circling

and dancing like the atoms of Eliot and Rumi

defying astronomers like Al-Biruni

who worked so hard to separate the fantasies of astrology from the mathematics of astronomy;

all that fine distinction was now in peril, now that atoms danced an unpredictable dance

out of this world and into the next, now that God reasserted Himself

in gamma rays and ways we’d never seen

and ways that physicists could see were totally unpredictable

like Heisenberg on steroids the mystic atoms ran into the void and back again

while further afield each star was an electron unknown

each galaxy a nimble thread in a tapestry as tall as the Empire State Building and seventy billion times as wide.

All woven by what? What natural laws could now be passed? What instincts obeyed,

but those that made a deeper sense

beyond the logic that could no longer be followed to predictable ends

now that we could no longer call back the falcon

or call the mystic’s logic illogical,

logic itself having slipped the noose

like the desert birds of Yeats.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer

The deepest truth could now be anything, even the very thing we need

even the faintest glimmer of soul would be better than Sartre’s nothing

would be as likely as that nothing, that stumbling dance of chaos

that godless Fall into broken dreams and the emptiness of it all.

Better spinning worlds unseen and Sufi atoms than grounded dreams.

Better light and serial questions leading only to Mystery

than this blood-dimmed tide, this grim darkness of eternal night.

Giordano Bruno

So, sometime in the 1920s the old dream factories opened their doors again

and the Church was quick to advertise a miraculous giravolta

reversing the damage done by condemning Copernicus and Galileo

and by disparaging the infinite worlds of Giordano Bruno

last seen in 1600 in the Field of the Flowers

hanging upside down and naked and burning at the stake

for daring to question the divinity of Jesus

and for dreaming of worlds beyond the Vatican’s setting sun

As his flesh burnt, did Bruno see the pole star to his wandering bark?*

Was he pulled upward by some unseen structure as of yet undreamed

by mystic physicists in a bubble, beyond Hubble’s bubble dream?

Was his spirit lifted upward, away from the flames that tore muscle from bone,

toward some home amid the stars that shone in the night

ten billion years before someone in an old book wrote, Let there be Light?

————

* wandering bark - in “Sonnet 116,” Shakespeare sees Love as a fixed star (like Polaris, the pole-star) that leads the sailor in a storm back to safety. Love is “the ever-fixéd mark / That looks on tempests and is never shaken. / It is the star to every wandering bark / Whose worth’s unknown although his [its] height be taken.”

🧩

Next: 🧩 Huxley’s Definition