Collected Works ✏️ Vancouver

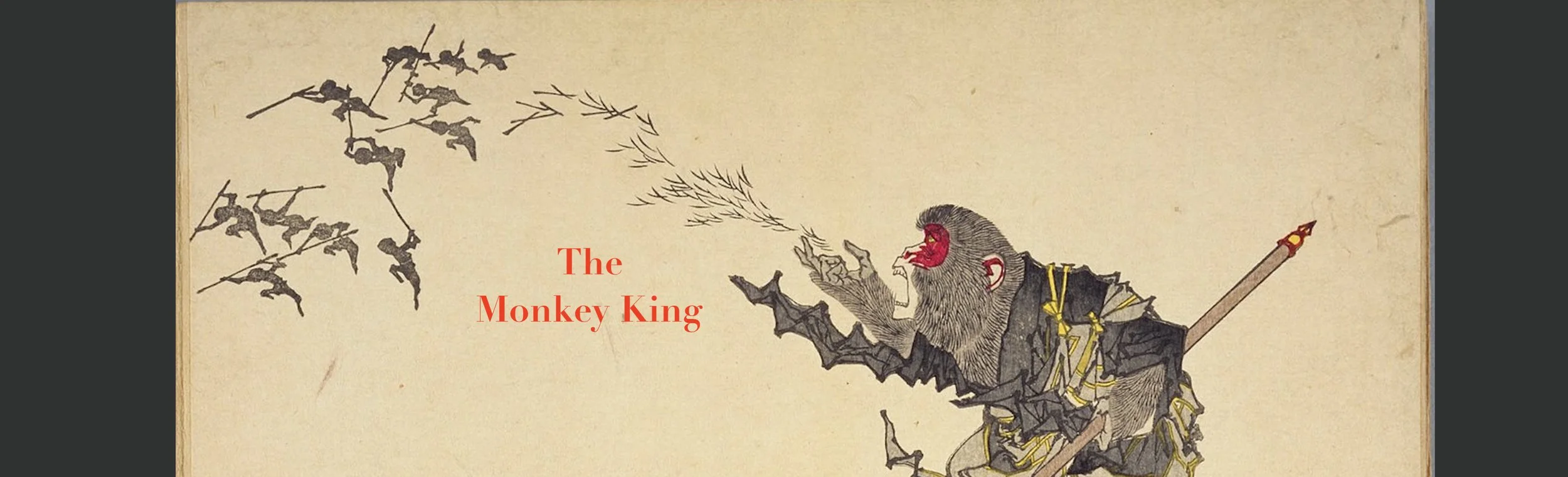

The Monkey King

10:00 AM

Old Rex is looking more and more like Captain Ahab, striding from poop to forecastle, eying the sluggards, the procrastinators, the Wreck Beach layabouts — all the scallywags and drivelling idiots who’ll walk the plank, ere long. Destination: The Deep Blue Sea.

Who does he think he is, Agamemnon? And who does he think we are, blue-eyes slaves from the Volga and Danube? Do we bark like dogs, like bar bar barbarians? It’s time to join Juniper, and get him down from his high Greek horse.

I’m not sure if my argument is a reaction to his haughty Classicism or simply what I think.

Loose Ends

The Classical Graeco-Roman epic was bound to collapse. Moreover, it was never that unique in the first place. In its journey of discovery, the Western epic was bound to sail forth and discover that it too was being discovered by other epics.

The epic sailed beyond the Pillars of Hercules and into the world ocean, a sea of unknown stories. It sailed mainly in three directions: north to the Baltic and the cataclysm of Loki, with its echoes of Armageddon and Resurrection; west to the fall of Teotihuacan and the rise (and fall) of the Two Towers (here England and York renewed themselves in a hundred different ways); and finally south, on the rolling heels of Vasco da Gama, around the Cape of Good Hope to the other side of the Middle East — that side where we once imagined a Whore on her diamond throne, a Sultanate of snakes and monkeys, and a Xanadu complete with floating domes and miracles of rare device.

What we found there was far more philosophical and far more realistic than we imagined. Instead of the lost kingdom of Prester John and a host of talking snakes, we found Gilgamesh in the existential angst of the second millennium BC, and we found Krishna discoursing on infinite cycles of time.

Yet as the Western epic comes apart and exposes its limitations, the global epic is born. It’s as if we were on a Greek island waiting for the hero to return, and for the beginning to unite with the end.

Each day we wove the bright world into fantasy, and each night the daylight was lost in night, our daydreams unravelled, and we thought of other things.

But we can still take these loose ends and bring them back together, not just with themselves but with other strands, warped and woven from far-off beaches swaying with palm and frangipani. We can take all the loose ends of the Athena to London line and tie them up into a ball, round and spinning, blue and green and brown, round as the world.

In her essay, “Penelope’s Loom and Mars Retrograde,” Safron Rosi writes: “In cosmic terms, the warp corresponds to the archetypal or divine principles of the world and the weft is the time, place and conditions in which those archetypal energies manifest. The Hindu concept of Śruti, the vertical warp, corresponds to the transcendent principles of the universe. Smṛti, the horizontal weft, is the human interpretations and applications of those principles in life. Together these threads weave the world as a garment of divinity.”

I put my pen down at the end of this sentence. “A garment of infinity.” So far, so good. I take a deep breath, and soldier on.

The epic isn’t a linear and logical thing, with a start and an end. Nor is it a national or ethnic thing. It’s a human thing. The creation and dissolution of the epic can be seen in the successive generations of gods from Chronus to Zeus, but it can also bee seen in the generations from Enlil to Ea to Marduk. And all of these generations can be seen in the cosmic destructions and creations of Shiva.

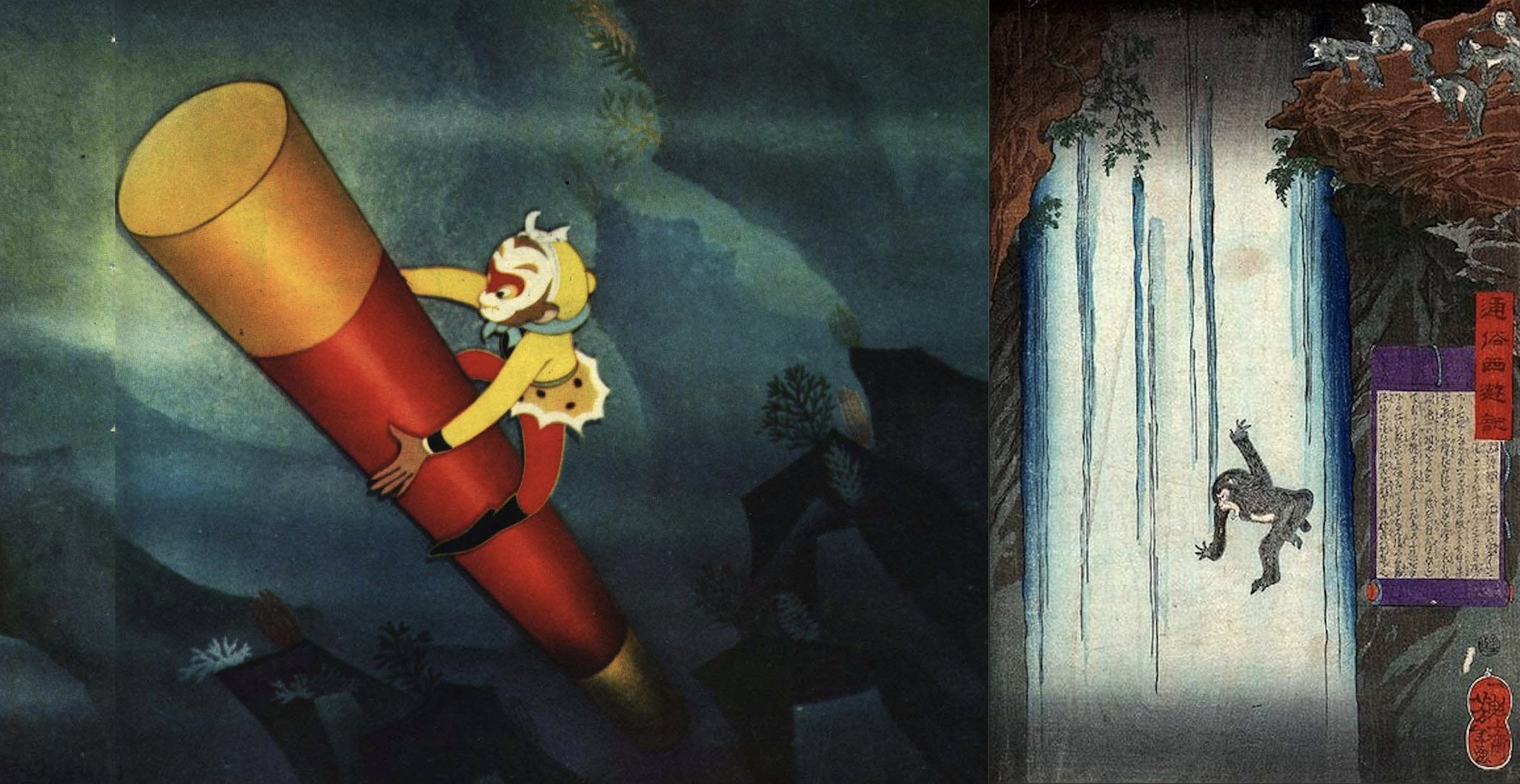

The epic doesn’t just take us to Rome and London, but also to Lindisfarne and Reykyvik. And it doesn’t just come from Greece, but also from Sumer and Akkad, from the Cedar Forest of the monster Humbaba, the gilded fortress-city of Uruk, and the dark underworld of Ereshkagil. From there it travels north-east, following the monkey-trails to China, or south-east over the Zagros Mountains, across Zarathustra’s perilous bridge between Good and Evil, and into the Thar Desert and the jungles of Southern India.

There, at the edge of the world, one imagines that one might find peace, like Odysseus finally reaching his home on faraway Ithaca. But there’s no end, no teleological completion, neither in myth nor cosmology. Instead, one generation of gods merely takes over from another. Life must go on. Odysseus has finished his travels but he must still battle the neighbours who are circling his beloved Penelope, who is eyeing the suitors and is suspicious (for whatever reason…) of her returning husband. Meanwhile, deep in the jungles of Southern India the ten-headed demon Ravanna makes a play for the wife of the great hero Rama. Further north, Monkey throws his magic army sticks into the sky.

We live in a postcolonial world, and if we’re going to explore meaning, we’d better dispense with longitudinal blinders. The Times They Are A —

⛔️

I suspect that Old Rex of the Restive Dinosaur Bones won’t like this at all, what with his echoing memories of the British Raj, punkawallahs, cricket, and tea on the maidan. I need to reorient — or rather deorient — my argument, leaving behind Vyasa and Ganesh, Hanuman and the Monkey King. It’s hard, though, because above Hanuman and Monkey circle the Seven Fairies. Like apsaras and Aladdin, they beckon me through the air, up up and away into the ether.

Yet back in the Greek world there’s always Helen and Aphrodite, Circe and Calypso, not to mention Eliot’s wonderful mermaids, singing each to each. I’ll have to leave the maidens and the Monkey flying through the skies for another day.

I have to leave behind me the hundreds of thousands of tales from Persia to China, from the Arabian Nights to the Puranas, as well as the grand epics about Monkey Kings, epic battles, holy love and forest demons. I can use them as context, carefully, yet if I want to pass this exam I need to focus on Europe. Closer to home, where the prejudices are greatest…

We live in a postcolonial world, and if we’re going to explore meaning, we’d better dispense with longitudinal blinders. The Times They Are A —This outward expansion, beyond the contours of Greece and Rome, can be found within the Western epic itself — in Dante’s Comedy and Tennyson’s “Ulysses.” For even after Odysseus returns to Ithaca, and even after he slaughters the interlopers and settles his affairs, Dante and Tennyson imagine Odysseus with an unquenchable need to leave Ithaca, to find new worlds, and to “follow knowledge like a sinking star.”

Instead of tying everything together, and bringing us back where we began, like Dante on the Tuscan slope, the epic starts to go everywhere, and we with it. From pantheism to monotheism, from gods to God, from belief to skepticism, from the unity of the Western Cultural Emperium to the vastness of the world.

Byron got this right in Don Juan, where he touts every epic convention in the book and then breaks all the rules, and throws the book away. He tells us he’ll write twelve books about overwhelming underworld secrets and about great sea battles, but then gives us transvestites in harems and a 13th canto, then a 14th, a 15th, a 16th, and then keeps on writing until his untimely death in Missolonghi, with violent fever, in love with an adolescent Greek boy.

✏️

Next: ✏️ 1825

Contents - Characters - Glossary: A-F∙G-Z - Maps - Storylines