The Double Refuge 🎚 The Priest’s Dilemma

Nineveh

Dates - Goblet, 612 BC - Infernos

🎚

Dates

During his preparatory year at la Maison, Albert made lists of dates. He followed in the footsteps of George Smith, who tied down the Elamite invasion of Babylon to 2280 BC, the Jewish tribute to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III to 841 BC, and the eclipse of the sun to 763 BC. This way of proceeding seemed promising, as it suggested that there was indeed a historical basis for the claims of the Old Testament.

Albert was told by his superiors that these dates would lead triumphantly to the destruction of Nineveh in 612 BC. He was told that 612 put an end to the barbarism of the Ancient pagan world. That it ushered in the truth of the Jewish Word, whose final glory was to defeat the paganism of Athens and Rome. That the burial of their occult tablets, along with the abandonment of cuneiform, laid Ishtar and Erishkigal, and all the other whores of Babylon, five cubits in the earth.

Yet by the end of his preparatory year Albert began to fear that this happy ending was only the beginning. In 1919, The Irish poet W.B. Yeats imagined in "The Second Coming" that history revolved in 2000-year cycles: after two thousand years, the Ancient beasts of polytheism were defeated by the Christ child; two thousand years after that, smack in the middle of the Modern Age, the beasts returned:

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Modernism unleashed the chaos the gods represented, a chaos worse than the original Greek Chaos out of which everything was rumoured to take shape. How deep into the heavens would we now have to look to see the darkness upon the face of the deep, to see the spirit of God hovering over the surface of the waters?

Modernism also unleashed an entirely new framework of history, of time itself. While Yeats managed to put his pagan resurrection into a Christian timeline, Albert worried that this Christian timeframe was itself an illusion. At best, it was an understandable distortion based on two thousand years of Christian time — a framework his fellow initiates referred to with a sense of pride, a sense of ownership over history itself: Before Christ, Anno Domini; avant J-C, après J-C. He remembered Cardinal Desmoines saying, At least the rest of the world got that right! And yet Albert feared that this Biblical timeline might be less relevant to the six thousand years of human history than Luther or the Pope imagined.

Yeats' chronology worked in twos, fours, and sixes, aligning itself with the traditional history of Christianity:

4000 BC Creation

+ 2000

= 2000 BC = Beasts

+ 2000

= 0 BC / AD = Jesus

+ 2000

= 2000 AD = Beasts

The time-frame of Assyriology on the other hand worked in threes and sixes. He feared that it went like this, roughly:

4000 BC = Birth of Cuneiform

+ 3000

= 1000 BC = Burial of Cuneiform

+ 3000

= 2000 AD = Resurrection of Cuneiform

Goblet, 612 BC

Albert had imagined, in his youthful optimism

(while the cathedral of Notre Dame still towered above him

with its holy cross hovering like Saint Michael over the gargoyles

and the demons of doubt with their red goblets and offerings)

that an angry God buried Nineveh in 612 BC

buried it deeper than Greece and Rome

Trojan columns deep

because of His anger

at their homosexual bent

the falseness of their idols

the presumption of their gods and

the sultry, impudent look on the face of Ishtar.

And there it lay, a broken Babylon with its ancient tablets

and its fallen towers, mute in time, as if it never mattered.

And on the pedestal these words appear:

"My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!"

Nothing beside remains: round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

(Shelley, 1818)

And yet I also know that

i. it wasn't God who directed the troops against Nineveh, and thereby gave a metaphoric burial to the cuneiform script and all it meant. It was a coalition of Babylonians, Persians, Medes, Chaldeans, Armenians, Scythians, and Cimmerians; and I know that

ii. it took a thousand years for the Phoenician script to replace cuneiform, which was finally dead and buried by the time of Christ. Christian history wasn’t an upward spiral to Truth, just as pagan history wasn’t a downward spiral to Error.

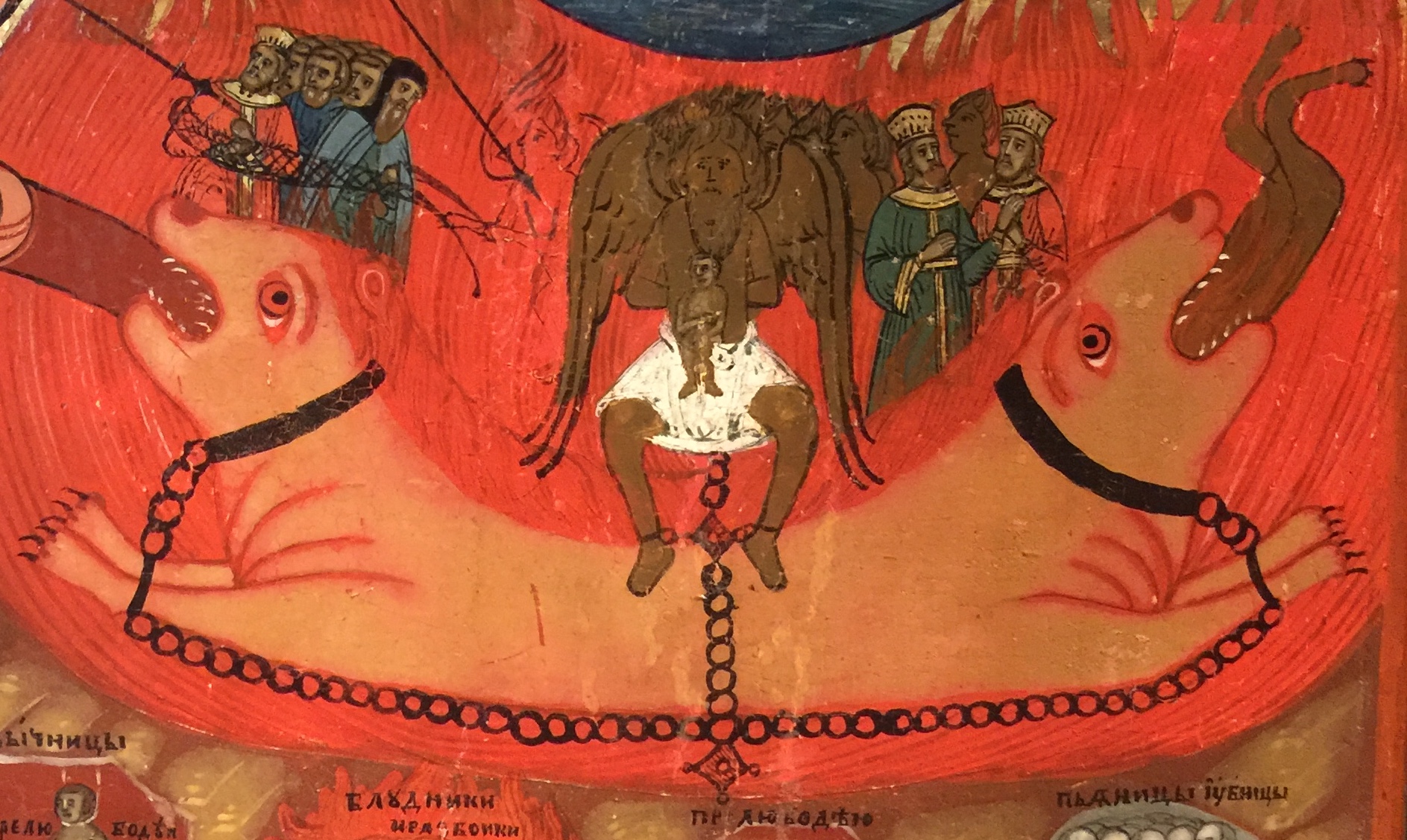

Infernos

I know that

iii. it is too convenient to imagine cuneiform as some sort of evil script

some sort of primeval incantation of letters and numbers

base ten and base sixty adding up malevolently

and falling down into the Inferno

10 X 60 + 60 + 6 = 666

safely buried

in pagan

ruin

,

as if to corroborate the dominion of the Jewish God

victorious over the Babylonian whore masters

the history of Mesopotamia reduced

to the Sumerian malefactors

Akkadian sluts and the

twisted idolators

of Ishtar and

Ba'al

.

And I know that

iv. when Christian civilization finally flourished, it didn't come alone, unsupported by the phalanx of time, the archers of free thought, or the battalions of science. Liberal democracy, perhaps the most profound of human ideals, was born in what one reactionary priest called that terrible century of Darwin and his monkey men. As if he’d make Galileo repent once more, if he could. As if truth wasn’t the finest thing.

The way Albert saw it, truth was inviolable, the only thing that mattered dans ce bas monde. He felt that truth was a community without which there could be no communion. If there were no fishermen, potters, biologists, or vintners, there could be no final supper. If there were no doctors of medicine and no human body, there could be no divine transubstantiation.

In this he was a follower of Voltaire. He was willing to tear down the Church itself if it counselled blind allegiance. If it ever tried again to silence men like Galileo.

Écrasez l'infâme. A few of his fellow seminarians still feared Voltaire's virulent phrase. But he lived by it. What were the words of Jesus if he didn't? How could the Truth be separated from the Light and the Way? How could the body be separated from the experience of drinking the wine? And wasn't this transubstantiation our link — no, more than this, our union — with the Divine?

He also loved Voltaire because he said of Calvin and Zwingli, "If they condemned celibacy in the priests, and opened the gates of the convents, it was only to turn all society into a convent. Shows and entertainments were expressly forbidden by their religion; and for more than two hundred years there was not a single musical instrument allowed in the city of Geneva."

To Albert the Rosetta Stone and the Behistun Inscription were beautiful, in the same way that the stele of Hammurabi's laws was beautiful. And all of them were verifiable, all true in the Modern sense. After all, he lived in the 21st century, not the Middle Ages. Just because he decided to become a priest didn't mean he wanted to ignore the spiritual implications of history.

The Behistun Inscription was written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian, what some of his fellow priests called evil Babylonian, that Devil's tongue. They could hardly mention it without a sneer, which helped them to dismiss its history of numbers and legal codes, its sky-scraping tower to the stars, its astronomical observatories, its algebra, and, above all,

v. its stories; the old Babylonian, Akkadian, Sumerian stories, reaching back thousands of years — especially that old story about an angry god, an ark, a bird, and a new beginning, which in 1872 George Smith read aloud to the Prime Minister of England and to the Society of Biblical Archaeology. For the first time in two thousand years, an audience heard the Chaldean account of the Flood, The Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest work of great literature. 1872.

I wonder what Saint Francis would think of that?

🎚

Next: Que Sais-je?